SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Journalist Maro Enriquez had seen dead bodies before. But there’s a difference between seeing the remains of relatives during their wakes, and seeing someone who had just been killed.

When Enriquez was assigned by her then-employer, television giant GMA-7, to cover extrajudicial killings in former president Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war, trauma unfolded that made her question being in the job.

“That was my first time seeing murder victims’ corpses up close…. It was something I did not really want to see, but I had to because we had to take videos and photos of the crime scene,” said Enriquez.

In 2016, Enriquez was a segment producer for GMA-7. Duterte had just entered office, and it was the height of his deadly drug war.

“There was so much blood in the streets – it was so bad. And the neighbors were washing the blood away like it was nothing, like nothing brutal happened there,” she said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Enriquez also remembers hearing gunshots from one of the nights she was in the field. “Nagka-trauma ako sa baril (I gained trauma from guns) because of that,” she said.

The hours were “unforgiveable,” she said. Sleeping at the office was normal practice. An edit could go on hours into the night, and with a 7 am call time, producers and editors no longer thought of going home sometimes. They brought extra clothes and slept at their editing bays.

The distressing themes of what she covered, compounded by the grueling work schedule, took a toll on her mental health.

“It was really heavy. It’s like being between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, you’re already covering something very complicated, something very distressing. And on the other hand, you’re also distressed by the work hours, by the experience. So, parang walang kawala (it seemed like there was no escape),” she said.

This was the beginning of Enriquez’ journey to freelance journalism. To take this path would mean exchanging security of income for a sense of freedom, but it was a risk she was willing to take.

Because of the lack of backing from a publication, freelance journalists are sometimes regarded with less respect than mainstream journalists. While they share the values and passions of mainstream journalists, some are mistaken for, or lumped together with, hao shaos (fake journalists) and vloggers, who drop by coverages and media dinners, but don’t produce any stories.

According to Enriquez, some of her fellow freelancers reported being discriminated against by mainstream journalists for simply being freelance.

In a bid to assert their rights and amplify their plight, a handful of Filipino freelance journalists have begun to nationally organize. On October 21, the Filipino Freelance Journalists’ Guild (FFJ) was launched to focus on the needs, demands, and grievances of freelancers amid a “changing media landscape.”

(Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story indicated the official launch as October 26. This has been corrected to indicate October 21.)

Two years of “arduous organizing and research” led to this moment, where freelance journalists could come together and collectively voice their concerns.

Leaving the daily grind

At one point in her drug war coverage, Enriquez told her superiors that she wanted a break from covering heavy issues to pursue culture-related stories. While a story on mental health was granted, it was not always the case.

“We do not have the luxury of choosing the stories that we produce,” she recalled being told by her superiors.

“That was the turning point talaga na (that), okay, I will not be prioritized in this job. I might as well prioritize myself,” she said.

After two years with GMA, Enriquez left and began freelancing around late 2018.

It was a breath of fresh air. The flexibility of choosing what stories to pursue, when to pursue them, and having time for breaks upon being paid was something she had longed for while she was employed.

“We didn’t always get to do the stories that we wanted to do. And for me, I realized it’s important for me to do the stories that I really care about, not just the stories that need to be published immediately or need to be released,” she said.

Enriquez is now a director of FFJ.

Living to work

Geela Garcia, after graduating in 2019 with a communication degree, briefly went into the corporate world in the aviation industry. It wasn’t because she liked the job – she was financially preparing for the day she would become a freelance journalist.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and she was laid off after a year. She then took a job under content company Hinge, but it closed in 2021. Laid off twice at this point, Garcia felt that it was time to dive into the freelance world.

The pandemic brought excitement to Garcia, who also takes her own photos for her stories. There were so many stories to pursue, and virtually every sector could be explored in how the pandemic affected it. She applied for various grants, and she was willing to use up her savings just to fund her work.

In 2021, Garcia acquired her first grant. It was a story about the garlic peeling industry in Baseco, Manila – an indictment of the job crisis during the pandemic that pushed Filipino women into poorly paying jobs on top of their unpaid care work at home.

As Garcia built her portfolio and pursued stories close to her advocacies of food sovereignty and the environment, various challenges from her finances to her safety as a woman journalist propped up.

Once, Garcia had the opportunity to join a crew of fishermen who worked off the coast of Masinloc, Zambales, but she considered how she was covering the story on her own.

“When you stay in the sea, it’s going to take one to two days. And they were all men, while I would be the only woman. I really wanted to go because I wanted to take photos. But when I did my risk assessment, even if I believed they were good people, I didn’t go because I didn’t have a team. Because what if something happens at sea, and I didn’t have a newsroom to protect me?” she said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Financial stability also remained a challenge. Unlike employed journalists who have vehicles or transportation allowances, Garcia usually went around for fieldwork via public transportation. All her equipment comes from her own investments. Her friends understood that she could not easily come along on out-of-town vacations.

“There was a time [my friends and I] wanted to go to Quezon province. But I suddenly got a gig, and we had to move our trip three times. I think the people around me have accepted that if I suddenly have work, I am not in a position to say no, even if the pay is only say P2,000 or P5,000. I will have to say yes, because it’s a job,” she said.

“My work eats up my money, but also, I don’t like thinking that I’m wasting my money on being a freelancer when this is the life I want for myself. So I’ve come to accept that being a freelancer has become my cost of living,” she added.

Garcia is currently in Seville, Spain, taking up a teaching job under a year-long contract. She is also taking her time to build networks, research, and widen her perspective as a journalist. While she has more time for life outside of work now, anxiety remains over the uncertainty of not having a job once she returns to the Philippines by June 2024.

“When I return to the Philippines, I don’t know if there will be a grant opportunity for me by then… I’m able to survive now because of savings and because I [only look after myself]. But honestly, my financial situation is not good. I can never dream of owning a home, or even starting a family. All the normal milestones in life I’ve let go of, because of how difficult my financial situation is in freelance,” she said.

Garcia is set to join the FFJ once she returns to the Philippines.

“As freelancers, we’re on our own. But it’s important for us to form a union for our protection…this way, we can lobby things together. I’m optimistic about it,” she said.

Challenges in freelance

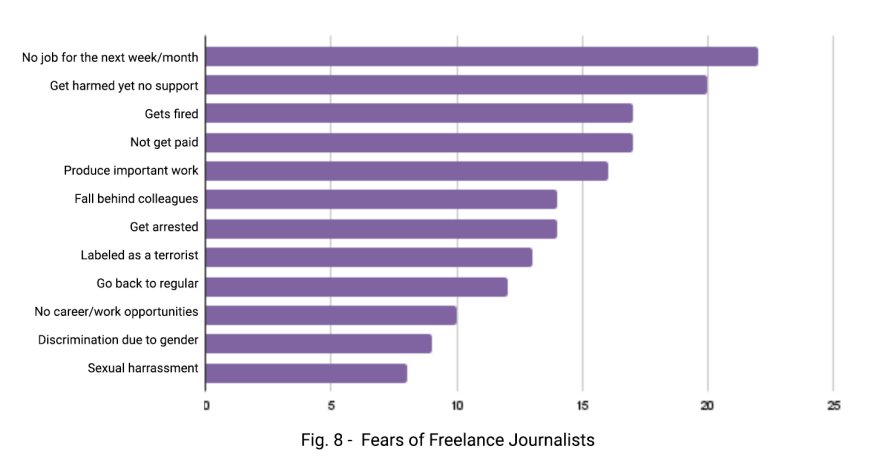

In 2021, with support from the International Federation of Journalists, the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP) came out with a study on freelance journalists in the Philippines. The top “fear” that the freelance journalists who participated in the study had was “no job for the next week/month.”

Majority, or 63% of the respondents, said they have difficulty finding assignments. A typical freelancer has 0 to 10 assignments, gigs, or projects in a month, most of which pay less than P5,000. These also push freelancers to seek additional employment outside of journalism.

Freelancers based in Metro Manila were found to be earning higher than those with employers from outside the region, and none of the freelancers with provincial employers earned above P15,000 monthly.

There is a tendency for newsrooms in general to low-ball freelancers, according to NUJP chair Jonathan de Santos. Around a quarter of NUJP members are freelancers.

Jazmin Tabuena, freelance photojournalist and FFJ board member, has a personal advocacy that all journalists should be paid well.

“We should push against the idea that just because we’re journalists, only passion will take us through. We should be compensated well,” said Tabuena.

“We need proper compensation to provide quality work in journalism. And if we don’t have that, we will not be able to provide quality news to the public because we ourselves are exhausted,” she added.

The need for a guild

According to NUJP chair De Santos, there was a local boom in freelance journalism after media giant ABS-CBN lost its franchise in 2020 and had to lay off thousands of its employees. This also coincided with the economic downturn during the COVID-19 pandemic, which also led to many Filipinos turning to freelance work.

With the increase in freelance journalists who began voicing out common concerns, Enriquez said that perhaps it was the right time for talks about forming a freelance journalists’ guild.

NUJP’s focus “for the longest time,” especially during the administration of former president Duterte, was the political aspect of press freedom, according to De Santos. It was what was needed at the time, especially with the Duterte administration’s crackdown on dissent and hostility towards the media, as seen in the ABS-CBN shutdown and attacks against Rappler.

Under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. – while De Santos refuses to label the political environment as “safer” – there is now more space for journalists to organize around their labor and economic rights.

In the near future, the 18- to 20-member guild hopes to organize more members and to make more freelancers realize that a guild can help lobby for their needs, such as better pay, and better working conditions. They also hope to craft a freelancers’ manifesto, which will be routed to media outfits to get their commitment to providing good working conditions for their stringers and contributors.

Garcia said one thing the guild can lobby for together is a minimum wage for freelancers.

Freedom of association remains an issue in the labor sector in general, with trade unionists harassed, red-tagged, and even killed. NUJP has been a target of such attacks as well.

“Any organization that has any sign of progressiveness to it is being met with violence here in the Philippines. So yes, we are anticipating [threats]. But at the same time, we hope that it does not come to that… we hope na hindi siya mauuwi sa red-tagging (we will not get to a point of red-tagging),” said Enriquez, adding that they are looking to set up a safety office.

Meanwhile, there is a Freelancers Protection Bill pending at the committee level of both chambers of Congress, looking to provide protections for the 1.5 million freelancers – not just journalists – in the Philippines. The lack of a formal employer-employee relationship, as well as “gaps” in Philippine labor laws, makes freelancers in the country prone to abuse and exploitation, according to Senator Joel Villanueva in his explanatory note.

The bill seeks to lay out the minimum rights of freelancers, which include the right to just compensation, the right to safe and healthy working conditions, the right to self-organize and collectively bargain, and the right to education and skills training, among others.

The FFJ said that the bill is a step in the right direction, but that more consultation with the sectors was needed to ensure the would-be law could fully protect freelancers.

“As good as its intention is, we believe that the bill can be honed further to fully protect freelancers. This can be done by holding more in-depth consultations, and spending more time with freelancers, so that all aspects of freelancing will be covered, and covered well, by the bill,” the FFJ said.

Freelancing for freedom

For Garcia, as difficult freelancing is, it is still the life she chooses. For her, freelancing is a fight for freedom – not only for herself, but for the subjects of her stories. Employed reporters often get caught up in the daily grind, but Garcia feels that with freelance, she is able to immerse in communities longer and tell stories from the ground.

In a story she wrote about the exploitation of Filipino fishermen in Ireland, she spoke to an undocumented fisherman’s family in General Santos. “Buti may mga taong tulad ‘nyo na pumupunta sa ‘min para lang makinig sa ‘min (Good thing there are people like you who come to us just to listen to our stories),” she remembers a source telling her – a thought that stayed with her.

“I am able to advance my advocacies as a freelancer better than if I were tied to a job. So in fighting for rights to food, land, the rights of the people in their fight for freedom from landlords, freedom from corporate agriculture… All of it is hand in hand in the struggle for liberation. All the stories I cover go back to my advocacy… to be free of the things that exploit us,” she said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] On the ILO probe into labor rights in the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/ILO-probe.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Unpaid care work by women is a public concern](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240725-unpaid-care-work-public-concern.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.