SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The latest move of the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a welcome development given the United Nations Human Rights Council’s (UN HRC’s) lackluster action against killings under former president Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs

ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan on June 24 sought a resumption of his probe after he determined that there were no genuine investigations being carried out by the Philippine government into the drug war killings.

Khan’s decision came despite numerous efforts of Duterte-era government agencies to shield the apparent lack of justice in the country, including the Department of Justice-led drug war review which Khan referred to as a mere “desk review… [that] by itself does not constitute investigative activity.”

The movements at the ICC are far from actions taken by the UN HRC, a UN body composed of 47 member-states supposed to promote the protection of human rights. Instead of opening an independent investigation into the killings, the council in October 2020 adopted a resolution giving technical assistance to address the situation in the Philippines.

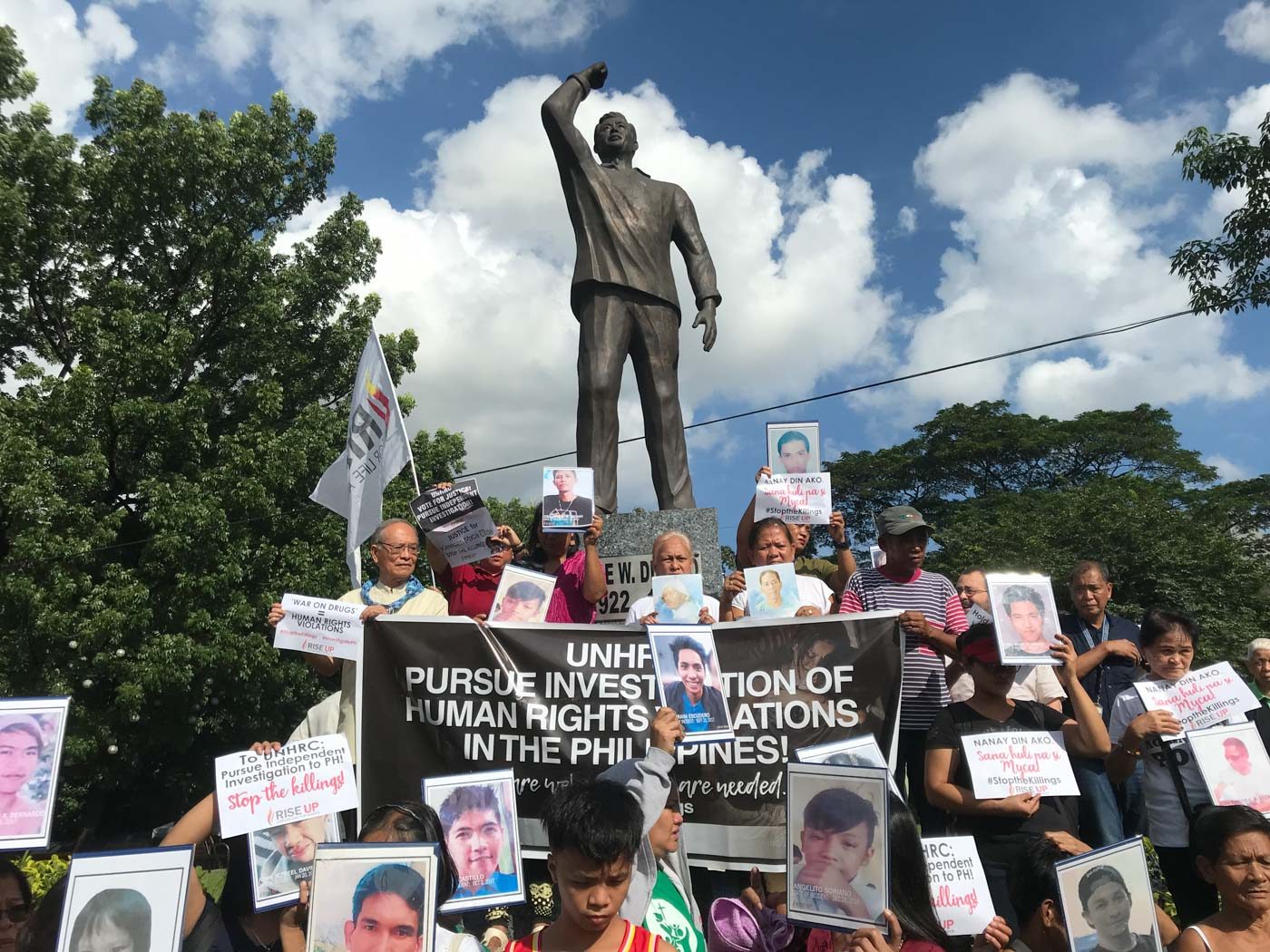

This move was widely criticized by human rights advocates as being too weak against the continued violence faced by Filipinos under Duterte, especially since the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN OHCHR) already released a comprehensive report detailing how killings were possibly incited by Duterte, how police planted guns in operations, and how local justice mechanisms aren’t enough to exact accountability.

Former UN special rapporteur Agnes Callamard, now secretary-general of Amnesty International, said the UN resolution “failed to address the massive killings, sending dangerous messages that justice can be denied,” and that the “international community had fell for pretend accountability.”

The findings of the ICC on how there is still no genuine accountability over drug war killings should trigger stronger actions from the UN HRC, according to Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) secretary-general Ellecer Carlos.

While the UN HRC and the ICC are different entities, they complement each other. Their reports and findings can trigger more post-crisis justice mechanisms that will not just hold perpetrators accountable, but also ensure that the extrajudicial killings won’t happen again.

“The ICC brings the highest accountable individuals to justice while a UN HRC-mandated independent investigative body makes a detailed report on the factors that gave rise to the mass violations,” Carlos told Rappler.

“The clear-cut and consistent findings and pronouncements of ICC offices and officials should be indications for the [UN HRC] member-states to at least consider a more just track in addressing the Philippine situation and helping victims in the country rediscover hope in obtaining justice,” he added.

Duterte’s drug war campaign led to at least 6,252 individuals killed in police operations, as of May 31, 2022, while human rights groups estimate the total number to reach up to 30,000 to include victims of vigilante-style killings.

Internal politics, discrediting rights groups in PH

It’s not that human rights groups failed to act fast or be more aggressive. In fact, since 2016, they have consistently called on the UN HRC to address the culture of violence and impunity in the country. They are usually present during council sessions where they engage with member-states.

Some countries were responsive, but just like other UN bodies, the council is not safe from internal politics primarily driven by the need to save face, especially amid a global challenge to human rights.

National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers president Edre Olalia, who has joined several UN HRC sessions in the past as part of civil society, said the council is really hemmed in by its “character, limitations, and contradictions” as a multilateral body composed of different countries that “understandably have their respective interests and backs to cover.”

“The UN HRC, while an important platform with its useful and helpful role, really fell short this time in decisively addressing the urgent issue,” he told Rappler.

Carlos, who also attended and engaged with the UN HRC on several occasions, said it didn’t help that the Duterte government launched a “deliberate and well-organized campaign” to discredit human rights groups.

“[The Duterte government has] convinced some member-states that our interventions to surface the truth in the Philippines by way of our accounts and human rights situationers have been politically motivated,” Carlos said.

“The independent and impartial evaluation of the ICC… clearly demonstrates objective findings without influence from the political opposition in the Philippines,” Carlos added.

Over the years, Rappler has received accounts that delegates of the Philippine government have openly maligned advocates during sessions in Geneva.

In fact, letters sent to the UN rights office from government-aligned organizations echo long-running rhetoric of the Duterte administration, including linking human rights groups to the Communist Party of the Philippines.

The government cited these letters as “indication of the state’s engagement with [civil society organizations] and [human rights defenders] in an enabling civic space.”

This is why most advocates remain guarded in the face of the UN Joint Human Rights Program, a product of the highly-criticized UN resolution. Well-placed sources told Rappler that the program is yet to concretely address the pressing issues that stemmed mostly from Duterte’s policies, including the violent war on drugs and even the continued red-tagging of individuals.

The killings also didn’t stop. More than 300 individuals were killed between the end of October 2020, the month when the UN resolution was adopted, to May 2022. Not one police officer was convicted over any of these deaths.

“The nagging question is that after all these years, various resolutions, reports, programs, technical assistance, capacity building, and other steps worthy in their own respect, how come there is still continuing and indefinite impunity that effectively sanctions and engenders the violations?” Olalia said.

Phil Robertson, Human Rights Watch (HRW) deputy director for Asia, told Rappler the response of the UN council betrayed the work of human rights defenders who have tirelessly documented the killings in the Philippines.

“Meaningful use of technical assistance presumes that the recipient agencies have the political will and serious intent to do something with those skills, and that was never the case with the Duterte administration,” he told Rappler.

“All [the Duterte government] did was use the resolution and the process it set out as an excuse to buy time in a vain hope that the international community would forget the ‘drug war’ slaughter,” Robertson added.

Next step?

The UN human rights office is set to submit a report during the 51st UN HRC session in September 2022 detailing the implementation of the technical assistance given to the Philippines. Member-states are also expected to engage in a dialogue regarding the progress of programs stated in the October 2020 resolution.

HRW’s Robertson said the council should craft a new resolution immediately that will create an “independent and impartial” international commission of inquiry that will investigate the thousands of killings under the Duterte administration.

“The specific requirements [of this commission should be] to seek accountability for all those responsible, regardless of their position or rank, and a clear directive to share with the ICC any information gathered that relates to crimes under the ICC’s mandate,” he said.

But beyond this, human rights groups are also looking forward to the scheduled participation of the Philippines in the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) this coming November 2022.

Undergoing UPR means UN HRC member-states will assess the human rights record of the Philippines, and give recommendations based on information gathered from several stakeholders, such as the government, civil society, other UN agencies, and the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

“It’s going to be the country’s report card on human rights under the Duterte administration,” former CHR commissioner Karen Gomez-Dumpit said, emphasizing that questions regarding the Duterte government will be answered during the review, including:

- What were the most serious violations experienced in the country?

- Who was left behind in public service delivery?

- Who were directly attacked and victimized?

- How was access to justice enabled for victims?

- Was the rule of law respected?

The last time the Philippines went through the UPR in 2017, the Duterte government rejected recommendations and calls to conduct investigations into the violent drug war that by then already saw thousands killed in police operations.

The outcome of the upcoming UPR of the Philippines should give President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. a “baseline to improve the situation on the ground.”

“A new government cannot say that it is the past administration’s record,” Dumpit said. “The Marcos administration has a continuing obligation to effectively respond to human rights violations of the past.

Not much has been said about the human rights agenda of the new administration. Marcos has yet to appoint members of the new CHR en banc. CHR is an independent commission tasked to investigate state abuses.

But Dumpit said Marcos can start by appointing the right people “if he desires to do good and be guided by human rights standards and principles” as it will lay a strong foundation for his governance.

The new commission – composed of four commissioners and one chairperson – must exemplify “an independent, robust, credible, competent, and incorruptible membership. It should also be enabled to speak out in safe spaces regarding the problems of the community, as well as viable solutions to these issues, in contrast to the CHR’s experience under the Duterte administration.

“[CHR] must be able to act as his advisor or conscience who can tell him upfront about human rights concerns without fear or favor,” she said.

“Unity does not mean the absence of a contrarian view and legitimate dissent, it also means heeding these views and acting on the concerns to alleviate the plight of victims and those most left behind,” Dumpit added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] The PDEA leaks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/vantage-point-pdea-probe.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] How Duterte can elude ICC arrest](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/thought-leaders-How-Duterte-elude-icc-arrest.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=272px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.