SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

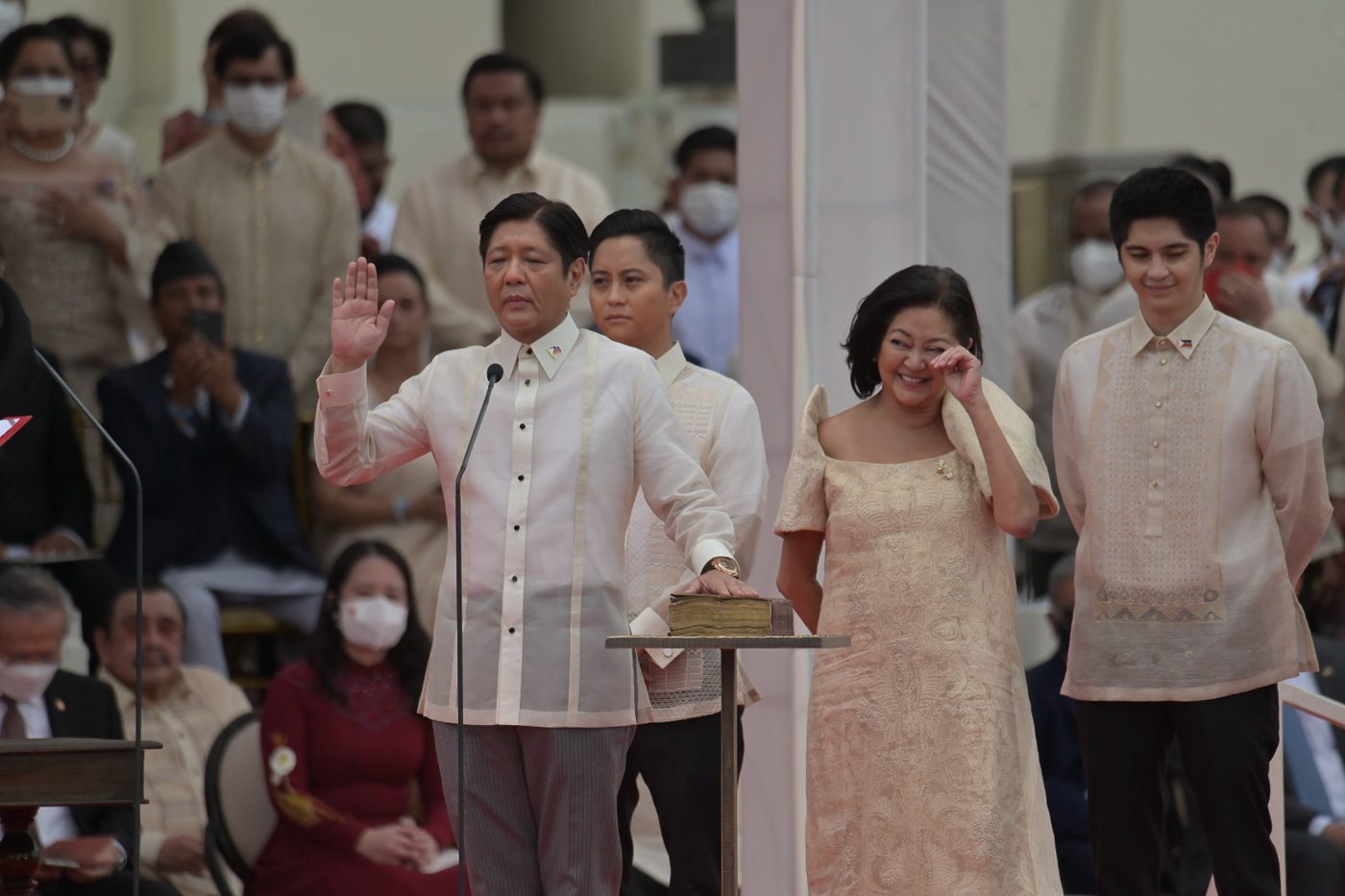

MANILA, Philippines – On the steps of the building where, as a young child, he once waited for his father so they could go home together, Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos Jr. took his oath at noon of June 30, 2022 as the 17th president of the Republic.

The reference – of him being the late president Ferdinand E. Marcos’ only son – was rarely made in the 2022 campaign, even as he and his campaign team evoked the image of the late strongman and made references to a once glorious past.

But when he spoke for the first time as chief executive, Marcos Jr. no longer held back in edifying the late dictator.

“I once knew a man who saw what little had been achieved since independence, in a land of people with the greatest potential for achievement; and yet they were poor. But he got it done; sometimes with the needed support; sometimes without. So will it be with his son. You will get no excuses from me,” said Marcos, drawing applause from an audience of foreign and local officials, select guests, and only a sliver of the 31 million who voted him President.

And just as quickly, he insisted: “I am here not to talk about the past.”

“I am here to tell you about our future. A future of sufficiency, even plenty; of readily available ways and means to get done what needs doing – by you, by me,” he said on the podium as his family, wife Liza and sons Ferdinand Alexander (Sandro), Joseph Simon, and William Vincent (Vinny) sat behind him.

Behind him, too, were Marcos family members who once resided in Malacañang Palace: former first lady Imelda Marcos and Senator Imee Marcos, who even held a government post while their father was in power. The significance of the image of the past reclaiming the present was not lost on many.

‘Politics of division’

In the 2022 campaign, Marcos and Vice President Sara Duterte’s promise was simple: “unity.” It was a pitch that, according to those who tracked internal polling and studies, resonated the most with the electorate.

Even with no concrete plan to speak of, the “Uniteam” tandem easily won as majority-elected leaders, Marcos with over 31.63 million votes and Duterte with over 32.21 million votes. They are the first majority-elected president and vice president since democracy was restored in the Philippines after the Marcoses were booted out in 1986.

The duo shunned most debates and forums, with Marcos attending only a “debate” sponsored by SMNI, a network owned by FBI-wanted doomsday pastor Apollo Quiboloy, who had earlier endorsed the tandem. Interactions with the media were few and far between, with sit-down interviews an even greater rarity. But it worked.

Again, in his inaugural speech, Marcos said his intent was to listen, not speak.

“I did not bother to think of rebutting my rivals. Instead, I searched for promising approaches better than the usual solutions. I listened to you. I did not lecture you [on] who has the biggest stake in our success,” he said.

While his critics questioned the readiness of a candidate who barely showed up, Marcos said the results of the 2022 elections showed voters “rejected the politics of division.”

He went on to claim that he “offended none of [his] rivals in this campaign,” a crucial message for a candidate claiming unity, never mind that online networks of his supporters were central in spreading disinformation against political rivals or that his team pushed lies and half-truths about himself and the late dictator’s rule.

“I listened instead to what they were saying and I saw little incompatibility with my own ideas: about jobs, fair wages, personal safety; and national strength, and ending want in a land of plenty,” he said.

All in the family

That Marcos and Duterte are members of political dynasties – one based in Ilocos Norte and the other in Davao City – is a sad norm in Philippine politics. Where parties are weak and non-existent, it’s personalities, often coming from entrenched dynasties, that dominate the electoral scene.

Marcos certainly isn’t the first former first child to ascend to the presidency himself – there’s the late Benigno Aquino III and Uniteam ally Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. But he would be the first to enter Malacañang with the baggage of a Marcos name.

On February 25, 1986, the Marcos family was forced to flee Malacañang after lording it over for two decades, in an uprising we now call the People Power Revolution.

The Marcos dynasty’s rise goes beyond a return to Malacañang.

Several members of the clan were elected in 2022, including Marcos’ eldest son, Ilocos Norte 1st District Representative Sandro Marcos. The 28-year-old led a special oath-taking ceremony for Ilocos Norte officials – including his governor cousin and vice governor aunt – at the Malacañang Palace after the vin d’honneur.

Marcos Jr. paints the first Marcos regime as one of promise and solutions. Survivors and loved ones of those tortured, disappeared, and killed during the Martial Law years remember differently. At the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, they took their own oath to “guard against tyranny” as the dictator’s son was sworn into office.

Mendiola Street near Malacañang Palace played host to an ill-attended “People’s Concert” later in the evening. As it began to drizzle, supporters were handed out red shirts and Marcos-branded face masks as they entered the concert “grounds,” historically the venue of protests during the first Marcos presidency and even after.

‘My dream, your dream’

An inauguration, according to historian Xiao Chua, should be about the electorate and not the elected – even if it’s Marcos’ face and name that’s plastered in event paraphernalia and tokens for guests.

It should be about the people – even in a civic and military parade where the military, uniformed services, and people standing for medical frontliners and overseas workers showcased themselves, while also saluting the newly-elected president.

It’s also the President’s way of setting the tone for the next six years.

In his speech, Marcos laid out his dream for the nation, which he said, is based on the average Filipino’s dreams for themselves. “Sa pangarap na maging mapayapa ang ating bansa, ang pangarap ‘nyo ay pangarap ko! Sa pangarap na maging maunlad ang ating bansa, ang pangarap ‘nyo ay pangarap ko! At sa pangarap na maging mas masinang ang kinabukasan natin at ang ating mga anak, ang pangarap ‘nyo ay pangarap ko!” he said, reading off one of the few Filipino parts of his speech.

(In your dream of a peaceful nation, your dream is mine too. In the dream of a prosperous country, your dream is mine too. And in the dream of a brighter future for ourselves and our children, your dream is mine too!)

He also went from urging Filipinos to participate in governance and nation-building to saying that he would still deliver on his promises without “[predicating his promise]… on [their] cooperation.”

“Whatever is in a person to make changes for the better of others, I lay before you now in my commitment. I will try to spare you; you have your other responsibilities to carry. But I will not spare myself – from shedding the last bead of sweat or giving the last ounce of courage and sacrifice,” said Marcos.

In the aftermath of what’s usually a grueling and nasty election campaign, the default message of any inauguration is almost always that of unity.

The 2022 polls were as divisive as they could get, even for a majority-elected president. There are the wounds of Martial Law under the first President Marcos that have yet to heal, disinformation that’s only gotten worse in the campaign, and the resurgence and continued dominance of powerful political clans allied with both President Marcos Jr. and Vice President Duterte.

President Marcos has promised that we, the Filipino people, “will build [the economy] back better” and emphasized the following priorities: agriculture, which he himself will lead; trade policy and food sufficiency; energy supply; education; health crisis preparedness, although he has yet to announce a health secretary; overseas workers’ protection, infrastructure, tourism, and the climate crisis.

In speaking about the challenges of the climate crisis, Marcos promised to address the country’s vulnerabilities despite having a small carbon footprint, while not “[shrinking] from responsibility” as a top plastics producer.

“You will not be disappointed. So do not be afraid,” he said.

There are many things to worry about for many sectors of Filipino society. With a majority win comes mandate and political capital – as well as the high expectations of more than half of the electorate.

“And if you ask me why I am so confident of the future, I will answer you simply, that I have 110 million reasons to start with. Such is my faith in the Filipino,” he added.

Marcos has proven that a network of disinformation in one’s favor, tactical alliances, decades-long rehabilitation of reputation, and continuity wrapped with a promise of unity are more than enough to win a Philippine election. But will all these suffice to govern? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.