SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Commuting in Metro Manila is a daily struggle.

The situation was exacerbated during the pandemic, when the government imposed restrictions and prohibited cars and public utility vehicles from plying the roads.

Because of this, many people have turned to biking as an alternative mode of transport. In response, local governments across the country created pop-up bike lanes. The Department of Transportation (DOTr) even opened the 313-kilometer bike lane network in Metro Manila in 2021.

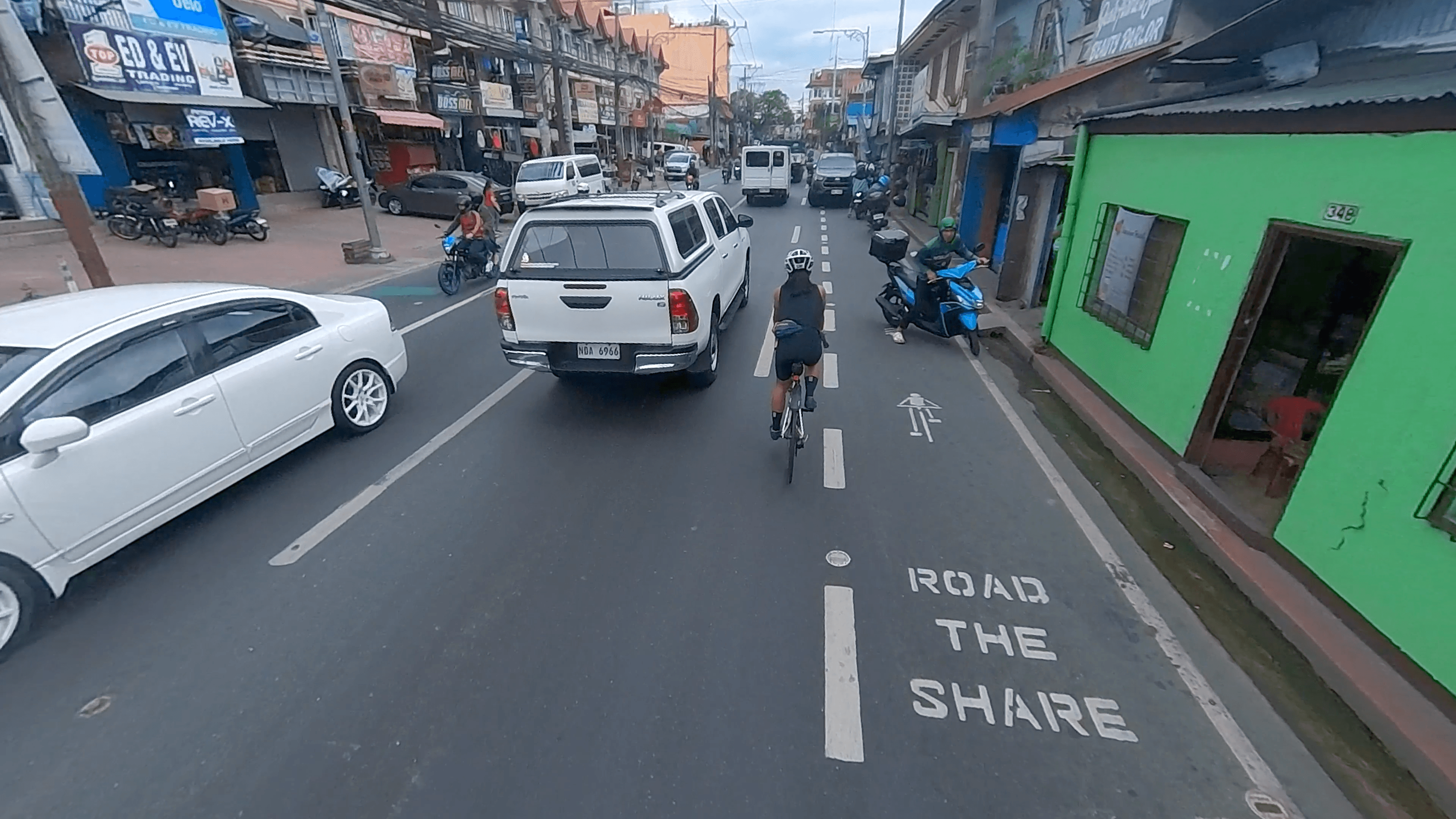

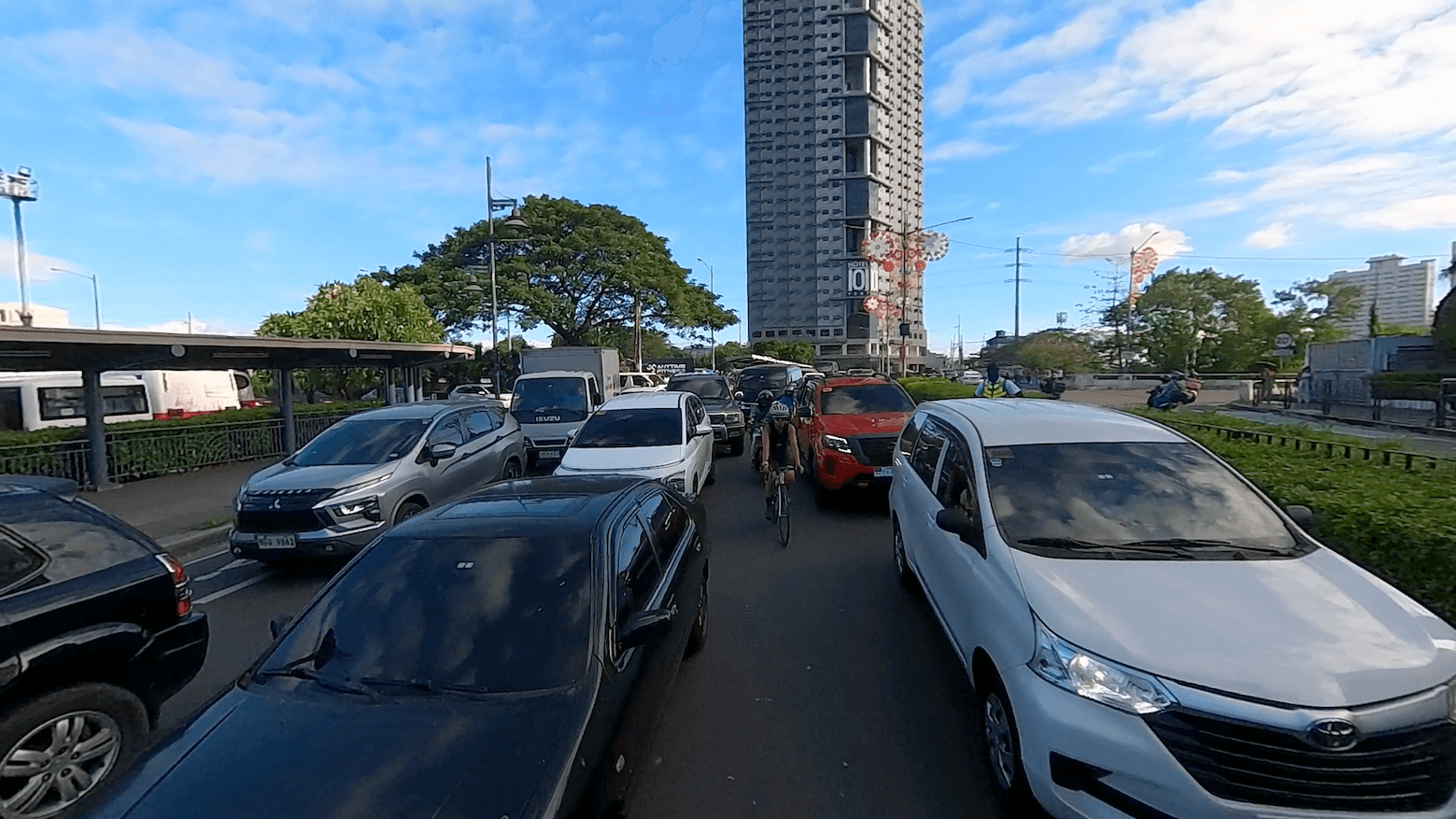

But just how friendly are Metro Manila’s roads for bike commuters?

To find out how bike-friendly Metro Manila is, Rappler rode a loop of 120 kilometers around the capital in January for a documentary. Riding 100 kilometers or more is part of the bucket list of many bikers due to its sheer distance and the challenge it poses.

The loop covered Pasig, Marikina, Quezon City, Valenzuela, Malabon, Caloocan, Manila, Pasay, Parañaque, Las Piñas, Muntinlupa, and Taguig.

The loop went through 21 major roads:

- Amang Rodriguez Avenue

- Marcos Highway

- Aurora Boulevard

- EDSA

- East Avenue

- Visayas Avenue

- Mindanao Avenue

- Maysan Road

- Manila North Road

- Rizal Avenue

- Roxas Boulevard

- Quirino Avenue

- Diego Cera Avenue

- Alabang-Zapote Road

- Daang Hari Road

- Daang Reyna

- Manila South Road

- East Service Road

- C-5 Road

- Bonifacio Global City

- C-6 Road

The East Service Road was split into two in the reviews, owing to the completely different conditions of the section from Muntinlupa to Bicutan beside the South Luzon Expressway, and the section from Bicutan Circle to C-5 in Taguig. In the former, there was no bike lane and the road was two-way, making it hard to overtake. The bike lane began northbound after Bicutan Circle.

This brought the total number of assessed road segments to 22.

The accumulated mileage of all roads assessed was 84 kilometers. The rest of the 120-kilometer loop involved inner and connecting roads.

How we graded bike-friendliness

To assess bike-friendliness, Rappler drew up criteria evaluating the bike lanes using four factors: lane width, road conditions, obstructions, and segregation.

These are factors that affect a biker’s safety on the road, also take into account the infrastructure the government put in place, and gauge the attitude of other motorists with respect to the lane and the bike commuter.

YARDSTICK. Rappler takes note of obstructions that hamper a bike commuter’s trip, such as potholes, manhole covers, and parked or encroaching vehicles. We assess bike infrastructure by operational width of the lanes and type of segregation used.

Only portions of the major roads covered in the loop were measured in the scorecard.

Lane width was evaluated using the Department of Public Works and Highways’ (DPWH) guidelines. Under Department Order (DO) No. 88 series of 2020, the DPWH prescribes a minimum of 1.22 meters to make way for a one-directional bike lane. The standard should measure 2.44 meters for a bidirectional bike lane.

Sections without bike lanes were graded an automatic zero.

Lane widths in Valenzuela and Malabon along Manila North Road differed slightly and were measured separately.

To assess road conditions, Rappler counted the number of manhole covers, potholes, steel plates, and drain grates.

On sections without bike lanes, manhole covers, potholes, steel plates, and drain grates placed on the rightmost side of the road, or where a bike commuter would most probably pass, were counted.

For obstructions, moving and parked vehicles, pipe laying works, and vendors encroaching on the bike lanes were also counted.

On sections without bike lanes, parked vehicles, pipe laying works, and vendors on the rightmost side of the road or where a bike commuter would most probably pass were likewise counted.

Rappler did not count moving vehicles sideswiping as there were no lanes whatsoever to count as encroachment.

We graded segregation based on infrastructure used: dashed painted lines, solid painted lines, solid painted lines with occasional barriers, and solid painted lines with barriers.

A completely segregated bikeway, as seen only along C-6, got a perfect score.

We rode the same route another time in February to measure lane widths and assess road conditions. Obstructions were counted from the footage taken by the camera installed on the bike on the day the documentary was filmed in January.

What we found

Ten out of the 22 segments rated poorly – this is 45% of the segments evaluated.

Bike-friendliness of a segment or city does not only rely on infrastructure, but also on quality, maintenance, and people’s attitudes toward active modes of transport.

C-6, which got an excellent score in segregation, failed when it came to obstructions because its wide bike lanes, at 2.95 meters, were predominantly used as parking spaces.

East Avenue in Quezon City was the only bike lane with sections of concrete barriers in the whole loop. It was 1 out of 4 segments that scored the highest under segregation, with a score of 3.

But East Avenue got an average score on obstructions for the same reason, as some of the concrete barriers were already broken – becoming another hazard that bike commuters have to be wary of.

Rizal Avenue, which traverses Caloocan and Manila, scored zero on all factors. The avenue connecting the north to the capital did not have bike lanes.

It had dismal road conditions and many obstructions, such as parked vehicles and several pipe laying works that would push the biker either toward the center or the left lane.

Roxas Boulevard, a major thoroughfare almost synonymous with Manila, got a failing mark. The Manila side of the boulevard did not have a bike lane despite being relatively wider than other roads in the city.

The bike lane along Roxas Boulevard started only from Pasay onwards. Along Parañaque, the lane was just a strip of solid white lines without a bicycle road marking.

Daang Reyna, despite not having any bike lanes at all, scored a 10 because of minimal roadblocks and obstructions. This could be attributed to the socioeconomic profile of the neighborhood, the wide space, and the less stressful environment because of the reduced volume of cars.

Bonifacio Global City (BGC) and C-6 segments scored the highest in the scorecard – but for different reasons.

BGC had better road conditions and little to no obstructions. But while C-6 had better conditions, the segment scored low on obstructions despite having the best segregation among all segments.

In a nutshell:

- Manila – represented by Rizal Avenue and its share of Roxas Boulevard – did not prioritize the establishment of bike lanes. Rizal Avenue got zero on all factors. It had no bike lanes, road conditions were dismal, and obstructions abounded.

- Las Piñas, via Diego Cera Avenue and Alabang-Zapote Road, may have wider lanes than most (both measuring 1.52 meters) but it failed to keep off obstructions. Road conditions were dismal.

- Taguig, via C-6, showed the best bike infrastructure. It was the road segment that got the highest score among others, getting a good rating. However, strict enforcement in C-6 was lacking as vehicles were parked on the segregated bike path.

- Quezon City was the only local government Rappler saw to have ongoing construction of bike infrastructure, while others’ bike infrastructure were slowly diminishing or hardly maintained. It was also the only local government to employ dedicated bike patrollers.

- Almost all of the bike lanes (95%) we passed in Metro Manila only had painted bike strips. Only 4 road segments had the occasional bollards or barriers.

While this report looked at width, conditions, obstructions, and segregation, the bike lane network in Metro Manila could be assessed further by connectivity, materials used on the lanes, and general maintenance.

Nighttime commuting by bike is also a different experience that could be evaluated separately.

Aside from the bike lane network, the quality of the commuting trip of a cyclist also depends on the availability of end-of-trip facilities like bike parking and shower areas in offices and establishments.

A separate road

Painted lanes with no bollards or other forms of barriers still open the bike lane to the encroachment of other vehicles. But this is the only infrastructure that a majority of bike lanes in Metro Manila can speak of.

So what should a bike lane network look like?

“If you want a network, you have to plan the bike lanes,” Jose Regin Regidor, director of the University of the Philippines Institute of Civil Engineering, told Rappler in an interview. “As if it’s a separate road.”

Regidor is one of the research fellows at the National Center for Transportation Studies who helped in formulating the Bike Lane Master Plan back in 2022. This was a joint effort between the DOTr and the United Nations Development Programme.

Even a master plan like this, said Regidor, should be reviewed regularly every three to five years.

Some of the existing popular guidelines for bike lane networks are the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), the Netherlands’ CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic (CROW), and the design guide from the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO).

In the Netherlands, more than 25% of trips are done by riding a bike, according to a 2018 briefer by the Dutch research agency National Institute for Public Health and the Environment.

“The number of bicycles in the country outnumbers the amount of people,” the briefer read. “Cycling is part of our way of life.”

This has contributed to a decrease in air and noise pollution, decongestion of roads, increased physical activity among low-income and ethnic minority adults, and economic benefits for users and establishment owners.

Gaps in design and mindset

In 2022, at the height of the pandemic cycling boom, the DOTr allotted P2 billion for cycling infrastructure in the country. The budget has since decreased in the following years, going down to P750 million in 2023 and P500 million in 2024.

In the same year, the DOTr opened its active transport office, which started as an ad hoc team.

Without any precedent to follow, the government largely based its bike infrastructure guidelines on NACTO since the Philippines’ road configuration is similar to that of the US.

Because of the novelty of Metro Manila’s bike infrastructure, there were design gaps in implementation.

An example would be the bike lane width. Under DO 88, the minimum width is 1.22 meters, but in the middle of implementation, the government had to revise guidelines to 1.5 meters after it became apparent that a 1.22-meter lane was too small, said Eldon Dionisio, project manager at the active transport office at DOTr.

Dionisio told Rappler that many local government units measured the bike lane from the outer rim of the pavement marking when they should have been measuring by operational width or the open space between two lanes.

Another gap in design is connectivity. Right now, there’s a push to remove bike lanes on national roads like EDSA. But Dionisio said this should not be the case.

“One main principle when you’re building a bike lane network is that it should be direct because cyclists use their own energy to move,” Dionisio said in a mix of Filipino and English. “You should provide them the most direct route.”

Beyond the gaps in design and infrastructure, the bigger struggle lies in entities that do not have active transport in their priorities. Dionisio called this a “misalignment of priorities.”

“We encounter, every now and then, apprehensions from different entities – may it be an individual, a group, an office, an agency – against building active transport infrastructure.”

Better public transport

For the longest time, Filipinos think in terms of using cars or commuting by public transport to go from one point to another.

Other modes of transport, like bikes, are seen as a cause of congestion rather than an additional mode of transport that people can use. A common argument against bike lanes is that they only contribute to more congestion of roads. But the conversation must go beyond car users and bikers, said Regidor.

“We’re always pitting the cars and the bikes when, in fact, the problem is public transport,” he said.

The professor said that there’s a natural synergy between good public transport and a working bike lane network.

In other countries in Europe, for example, commuters can take their bike with them on the train so that their bike commute trip is augmented by public transport.

For example, Regidor said that the current state of bike lanes along Marcos Highway could use some improvement, given that the highway is wide and there’s already a rail rapid transit line in the area.

Currently, the bike lane along Marcos Highway is 1.14 meters wide. At its widest, the bike lane measured 2.2 meters. But the wide lane was painted on the sidewalk and ended abruptly because of a barrier at a right turn where vehicles turn to enter Marikina.

That Marcos Highway remains congested during rush hours means more people are still opting to use cars.

Are people really shifting from private cars to public transport? We need to determine why they don’t.

Jose Regin Regidor

Making headway

Most bike lanes sprang across Metro Manila during the pandemic, when healthcare professionals and frontliners had to use bikes or other modes of active transport to get around. The national government then came out with guidelines for the establishment of bike lanes.

As restrictions eased and people went back to normal, most local governments also neglected to maintain the bike lanes. Bollards were removed, and paint started to fade. But one local government did the opposite by continuing to establish better lanes.

Even before the DPWH released DO No. 88, Quezon City had already started augmenting its 55-kilometer bike lane network that already existed before the pandemic.

According to Alberto Kimpo, assistant city administrator for operations in Quezon City, they used the AASHTO and NACTO guidelines in establishing the city’s bike lanes during the pandemic.

They used an engineering undergraduate thesis written by a staff member, plotting the ideal routes of bike lanes within the city.

Many advocates say that with the right infrastructure, more people will turn to bike commuting to get around.

But this is a problem that local governments have to contend with. Kimpo said that they are still in the process of generating more bike users. In 2021, they counted 22,000 biking trips in a two-week period; in the following year, the number dropped to 19,000 biking trips.

Aside from generating users, there’s also the issue of making do with the limited space available.

“It is a movement, it is a utilization of space that we really need to push as of the moment and to get more users to benefit from it,” Kimpo said in a mix of Filipino and English in an interview with Rappler.

“The roadways are not designed for active mobility. There is also a constant push for road widening.”

Still, Quezon City is continuing efforts to make bike lanes amid the failure of other local governments to maintain the lanes they created during the pandemic. A master plan is on the way.

Currently, the city is endeavoring to construct a Class I bike lane along the Quezon Memorial Circle in collaboration with the DOTr. A Class I bike lane is a designated protected path separate from a motor vehicle roadway. An existing example of a Class I bike lane in the Philippines is located along the Iloilo Diversion Road.

The Quezon Memorial Circle is set to have an elevated 3-meter bike lane made of red asphalt, planting strips, and another lane for pedestrians.

The push to prioritize active mobility relies on a clear vision and political will, said Kimpo.

“Of course, it also follows that the city takes very seriously its commitments vis-à-vis climate change.”

To a certain extent, political will could prevail over funding issues.

“There’s money,” said Kimpo. “Government will always have resources for these things. It’s really just a matter of channeling it towards the right investments that need to be done.” – Rappler.com

Improving active transportation facilities and policies is part of the call of various groups to #MakeManilaLiveable. On Rappler, we have created a dedicated space for stories and reports about liveability in Philippine cities. Learn more about the movement here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] Where the streets have no name](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/2-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=307px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Steps the Philippines can immediately take to reduce road casualties](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/Steps-the-Philippines-can-immediately-take-to-reduce-road-casualties.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[DOCUMENTARY] Biking 120 kilometers in Metro Manila](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/bike-commute-metro-manila-documentary-carousel-scaled.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=216px%2C0px%2C1440px%2C1440px)

![[EDITORIAL] Kamaynilaan para sa tao, hindi para sa mga sasakyan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-traffic-april-2024-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=410px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.