SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Faced with a rice crisis that isn’t likely to be solved in the short-term, the Philippines could learn a lesson or two from Japan which treats sweet potato as a mainstream health food and not a lowly root crop.

On a recent trip to Japan, I found all kinds of Japanese sweet potato food products, including this amazing purple mont blanc (fine thread) potato on whipped cream, vanilla ice cream, and a slice of sweet potato by specialty store, Imo Pippi.

The 1-mm-thin “thread” is made from Japanese sweet potato or satsumaimo in Nihongo. The dessert, which has been getting attention from tourists in post-pandemic Japan, sells for 1,300 yen (around P500). I didn’t try it since I found it too expensive; I did, however, try a cheaper one that an Imo Pippi outlet in Aomori City, northern Japan was selling – Roasted Sweet Potato topped with vanilla ice cream, which costs 680 yen (around P250).

The same store also sells Roasted Sweet Potato Brûlée (680 yen), Roasted Sweet Potato with Honey Butter (P680 yen), and plain Roasted Sweet Potatoes (220 yen per 100 grams or P83).

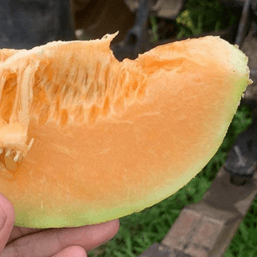

Comparing the Roasted Sweet Potato (minus the ice cream) with our boiled kamote, commonly cooked at home in rural Philippines, especially among indigenous peoples, it tastes almost the same, except that the Japanese sweet potato is little bit sweeter than our common variety, Ipomoea batatas. Japan has around 50 sweet potato varieties.

But wait, there’s more, lots more. Japan’s convenience stores or konbinis have a number of Japanese sweet potato products, proof that the root crop is certainly not a “poor man’s crop” in the Land of the Rising Sun as it is in the Philippines.

Take a look at some Japanese sweet potato products available in convenience stores, bread shops, vendo machines, as well as in souvenir shops in Japan’s airports.

Sweet Potato Bun

Sweet Potato Latte

Sweet Potato Tarts

Other Japanese sweet potato products available in konbinis include:

- Sweet potato donut

- Sweet potato pound cake

- Sweet Potato Financier (small French cake)

- Sweet Potato Baumkuchen (split cake)

- Sweet potato cream Daifuku (mochi with filling)

- Sweet potato Kouign-Amann (Breton cake)

- Sweet potato Mont Blanc (vermicelli)

- Sweet potato glazed and dice-cut

- Sweet potato ice cream brûlée

- Sweet potato chips

- Sweet potato cream bread

- Sweet potato crepe

- Sweet potato bread stick

- Sweet potato steamed cake.

A basic Baked Sweet Potato is being sold in Japan in popular retail chain Daiso and in groceries. One can count at least 20 iterations of the Japanese sweet potato.

Japanese sweet potatoes are said to be “dear to Japanese people’s hearts” due to its origin of being a “famine fighter.”

Sweet potatoes in Japan originated from central America in the 1600s. They spread to mainland Japan from the Satsuma region in southern Japan, thus the name satsuma-imo (imo means tuber). In the 18th century, Japan’s shogun (military commander) urged the people to plant sweet potatoes as an “emergency crop” that would be an alternative in case of low rice harvests, says Web Japan, a website operated by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“This is what led to sweet potatoes being grown in every region of Japan. Capable of growing even in poor or depleted soils and highly nutritious to boot, sweet potatoes have proven time and again to be a key source of nutrients whenever Japan has been hit by food shortages,” it adds.

“As new varieties of sweet potatoes emerge, along with new ways of enjoying them, their appeal will only grow bigger and brighter. Japanese people’s love for sweet potatoes shows no signs of slowing down,” says Web Japan.

‘Nangangamote’

Can the Philippines do to its kamote (not to be confused with ube or purple yam) what Japan has achieved with its satsumaimo?

In contrast to the stature of the sweet potato in Japan, the Philippines’ kamote is still generally seen as a lowly crop as exemplified by the Filipino metaphor “nangangamote” which means falling behind, being slow, or underachieving.

Except for kamote cue (deep-fried carmelized sweet potato), which is common in eateries, mostly sold on sidewalks and public markets in the Philippines, kamote (boiled, baked, roasted) is not usually offered in Filipino restaurants. Kamote, however, is an ingredient in the Philippines’ halo-halo (shaved ice dessert) and in ginataan, a coconut milk dessert. Philippine artisanal dessert maker Sebastian’s Ice Cream has Ginataang Halo-Halo, which includes yellow and orange kamote, in its seasonal offerings.

Our most common dish related to sweet potato is talbos ng kamote (sweet potato leaves), which uses the leaves but not the root. The Philippine sour soup sinigang may include kamote, but generally does not.

Over the past decades, there have been calls to change the stature of kamote in the country, and perhaps, the best way to do this is to stress the vegetable’s health benefits.

The International Potato Center (CIP), a global research-for-development organization advocating potato and sweet potatoes to address malnutrition and poverty, says sweet potato is a “valuable source of vitamins B, C, and E, and contains moderate levels of iron and zinc.”

It adds that the purple-fleshed sweet potato also contains cancer-preventing properties. “The anthocyanins that account for the purple pigmentation in this variety are powerful antioxidants and have good bioavailability, meaning they are easily absorbed by the human body,” the CIP, based in Lima, Peru, says.

It notes the sweet potatoes’ “long history as a life saver,” citing cases in Japan, China and Africa where sweet potato saved lives when disasters and plant diseases destroyed basic staples such as rice.

The CIP says sweet potato requires fewer inputs and less labor than other crops such as corn, and survives in poor soil and even during dry spells.

These findings support recent calls from a number of Filipino public officials to consider eating kamote or mixing corn with rice amid high rice prices.

“Adapt then adjust our, maybe our diet. Our diet is very traditional. We are used to eating rice during breakfast ang hirap mag-shift (it’s hard to shift), sa iba naman pandesal (others eat bread). But there are other alternatives like sweet potato or white corn,” said Trade and Industry Secretary Alfredo Pascual in a media forum last August, recalling studies done by the University of the Philippines which he used to head.

The fact that Pascual got flak for suggesting kamote instead of rice again reflects the lack of information among the populace on the health benefits of eating kamote.

Kamote as ‘superfood’

But it’s the nutrient value of kamote that is key to making it a mainstream food in the country, and the only thing lacking is a good marketing campaign, Dr. Lilibeth Laranang, the Philippines’ foremost expert on kamote, told Rappler.

In an interview on October 13, Friday, Laranang, a plant pathologist who has received several government awards for her sweet potato research and development, said Filipinos’ view of kamote has gone up a bit as more people have become health conscious.

Laranang calls kamote the “number one superfood,” citing, for instance, the orange-fleshed sweet potato variety’s advantage over other vegetables such as carrots or kalabasa (squash) in terms of its beta carotene content. In contrast to rice, she said kamote also has low glycemic index which makes it a good alternative for people with diabetes and for those trying to reduce weight.

“Dati, it’s a poor man’s crop pero hindi na. Nakikita na ang kahulugan sa nutrition (It used to be a poor man’s crop but not anymore. People are seeing it’s nutritional value),” she said.

Laranang, who taught in Tarlac Agricultural University (TAU) in Camiling for over 40 years, and her team in the school was instrumental in the production and utilization of sweet potato clean planting materials or SP-CPM. She is now the general manager of the Mayantoc Sweet Potato Clean Planting Materials Producers Cooperative, which sells these planting materials to farmers. Farmers use this to combat the kamote kulot, a virus that often hits the root crop.

Due to her efforts, Tarlac and other provinces in central Luzon have been able to reduce the incidence of this plant disease. Her team also played a big role in promoting sweet potato as food and animal feed, “thus elevating the status of the once ‘lowly kamote’ as a source of livelihood in the region,” said the Central Luzon Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development Consortium, a regional body that promotes agricultural development.

What kamote needs in the Philippines, Laranang said, is more marketing promotion and getting people to invest in food processing of kamote, similar to how it’s being done in Japan.

It’s important to promote kamote’s health benefits among children, especially in schools, she stressed, and should be a regular part of their diet. She said education will play a big part in changing people’s consciousness about kamote.

Laranang said there’s also a need to have more kamote food products beyond kamote cue or nilagang kamote (boiled sweet potato).

The former director of the Rootcrops Research and Training Center in TAU until she retired in 2022, Laranang said the Philippines can also have various sweet potato products like in Japan.

The TAU’s Rootcrops Research and Training Center has helped create products such as sweet potato buchi, sweet potato tamarind, sweet potato polvoron, sweet potato jam, sweet potato tart, camrind (candy balls made of sweet potato and tamarind), sweet potato juice, sweet potato jam, and sweet potato chips.

There’s also sweet potato flour for bread-making, and sweet potato powder which can be used to make kamote shake. These products are investment opportunities for entreprenuers.

Sweet Potato Wine, Ice Kreamote

The over three-decades-long collaborative work among scientists, extension workers, farmers, entrepreneurs, and elected officials in Tarlac shows that the Philippines can make kamote a major part of our processed food industry similar to ube (yam).

Partly due to the research and development work on sweet potato by the TAU, Tarlac is now the Philippines’ center of commercial kamote ventures. The town of Moncada, Tarlac, is perhaps the most active since it has commercialized two products – sweet potato wine and sweet potato ice cream.

Sweet potato became a major agricultural product of the town after lahar from the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo mixed with the soil and made it sandy, the type suitable for growing kamote.

In 2003, the town of Moncada pitched sweet potato as its One Town One Product (OTOP) to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI).

Knowing the health benefits of sweet potato, the Local Government Unit (LGU) of Moncada organized and trained a group of women to venture into processing, and they were able to make sweet potato chips, crunchies, polvoron, buchi, and sweet potato beverage.

In 2009, a DTI coordinator suggested to then-Moncada Mayor Benito Aquino the idea of sweet potato as wine. Aquino is credited as the inventor of the wine (thus the name Don Benito) with the help of DTI and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

A TAU expert was brought in to conduct skills training on sweet potato wine making. In 2010, the El Vino De Benito Wine Manufacturing Plant was established, leading to the successful production of Don Benito Sweet Potato Wine.

Packaging of the wine has been improved through the years, and today, it is being sold in slim 375 ml and frosted 500 ml bottles. There are two kinds – Classic Dry and Citrus Blend. The product was launched on February 12, 2010.

With support from the DOST, Moncada expanded its One Town One Product by adding the Hometown Delights Ice Kreamote (sweet potato ice cream), which was launched in June this year. It has six flavors – plain, ube (yam), cheese, chocolate, buko pandan, cookies and cream.

In the Visayas region in central Philippines where kamote is also abundantly produced, a similar collaboration between the Visayas State University’s (VSU) Philippine Rootcrop Research and Training Center, the Baybay City LGU, farmers’ cooperatives, and DOST has led to the commercialization of kamote chips and their own kamote ice cream. They also have Baybay Delights Sweet Potato Baby Food and Milk Drink meant to help address child malnutrition.

It will likely take time before these kamote products become popular and readily available in the Philippines. In the meantime, if you’ve been enticed by this article to eat something sweet but nutritious, why not go to the nearest wet market or supermarket, buy a kamote, boil or roast it, put some butter, honey, or vanilla ice cream on it and enjoy Philippine sweet potato for a fraction of the price in specialty dessert shops in Japan? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Brace yourselves for higher rice prices under Marcos](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/TL-high-price-rice-Marcos-August-25-2023.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.