SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[In This Economy] Spare a thought for the PH’s 90% learning poverty rate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/learning-poverty-august-30-2023.jpg)

It’s that time of the year again when we get to collectively lament the many woes of our education sector.

But this year, I would argue, we have more reasons to lament.

As usual, the nationwide reopening of schools was beset by the usual shortage of classrooms. But this year, the classroom shortfall rose to a whopping 159,000. That’s nearly twice the shortfall last year (just 91,000) and nearly four times the number education officials forecasted for this year (40,000).

Several reports also showed that many schools were inundated during their reopening. Typhoon Goring is largely to blame, but with climate change worsening, expect this kind of situation to devastate more schools in coming decades.

Most alarming, though, is the broader learning crisis we’re currently in, captured by a single grim statistic: as of 2019, the Philippines had a whopping 90% learning poverty rate.

That means that 9 in 10 of our Grade 5 students could not read and understand simple texts nor “make connections to understand key ideas.”

If that’s not an education crisis, I don’t know what is.

This finding comes from the 2019 Southeast Asia-Primary Learning Metrics (SEA-PLM), a “regional large-scale student learning assessment programme, designed by and for countries in Southeast Asia.”

Six countries participated in the first round of SEA-PLM: the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Lao PDR. The assessment focused on Grade 5 students’ proficiency in reading, writing, and math.

When it comes to Reading, 90% of Filipino students were not able to meet the minimum reading standard as defined by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Sure, Lao PDR got a worse learning poverty rate (98%), and other ASEAN countries fared just a bit better than us (Cambodia and Myanmar both got 89%). But the Philippines still ranked second to last in this group of countries, and Malaysia’s learning poverty rate was just 58%, while Vietnam’s was just 12%. (In another assessment, Vietnam’s learning poverty was a puny 2%.)

If you look at the other subjects, we didn’t do so well either (Figure 1). Our learning poverty in Writing was 72% (versus Vietnam’s 16%), while in Math it was 83% (versus Vietnam’s 8%).

Figure 1.

What’s broken?

We need to ask ourselves: How did our learning poverty rate get so high? How come Vietnam – a poorer country than us until the pandemic – is now leaving us in the dust? What is Vietnam doing so right, and what are we doing so wrong?

We don’t have space here to answer these big questions. But let me just share some thoughts.

I’ve heard some people blame the language used in SEA-PLM. Whereas the test in the Philippines was administered using English, in all other participating countries the test was translated into their native tongues: in Vietnam it was Vietnamese, in Cambodia it was Khmer, in Malaysia it was a mix of Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, and so on.

Note as well that in the other countries, such native tongues were the main official first languages of instructions they used in teaching primary-level Reading and Math. By contrast, in the Philippines, we use “Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education” (MTB-MLE) from Grades 1 to 3, then shift to Filipino and English from Grades 4 to 6 (right when SEA-PLM was administered).

The SEA-PLM said in their final report: “Quality assurance measures ensured that the intended meaning [of the assessment] was consistent across translated versions. All test materials were double translated and reconciled by a professional translation company.”

But still, they found that less than 10% of the Filipino kids who undertook the assessment said they speak the language of instruction at home. So, one might be forgiven for thinking that the language barrier may be a factor behind the Filipino kids’ poor performance.

On the other hand, there’s something in the report that kind of belies this.

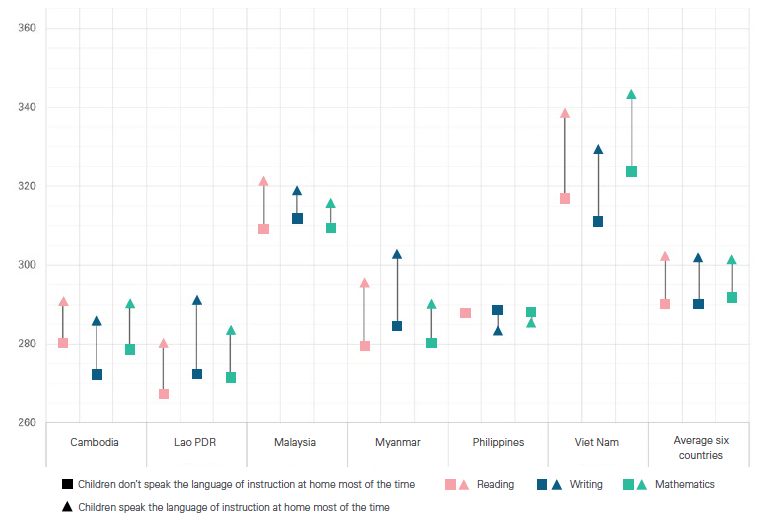

Figure 2 shows that there was hardly any difference in the test scores of Filipino kids who spoke and didn’t speak the language of instruction at home. (In fact, those who didn’t speak the language of instruction at home fared even better than those who did!)

Figure 2. Differences in scores based on language of instruction used at home. Source: SEA-PLM 2019 Main Regional Report (2020).

Other factors may be at play.

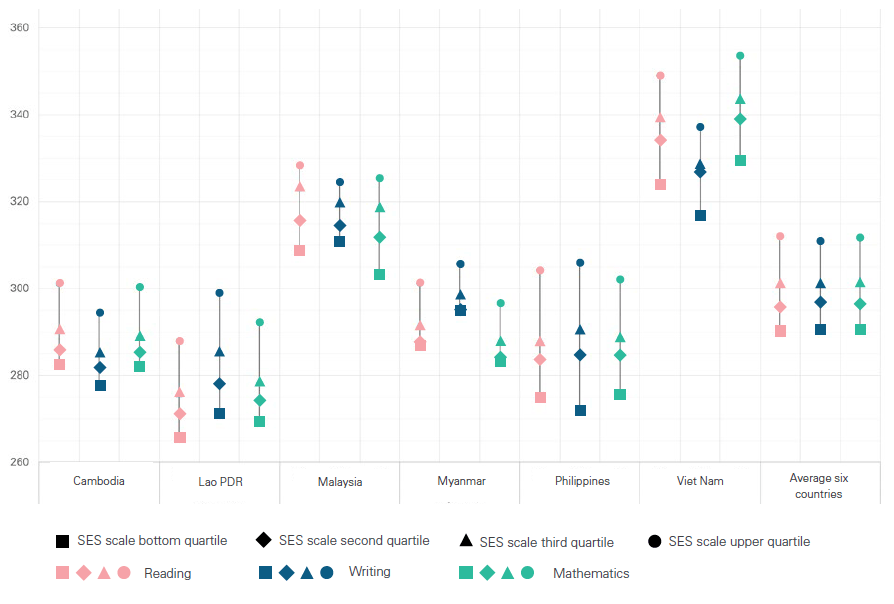

One of them could be socioeconomic status: Figure 3 shows that among the participating countries, we had the widest disparity in test scores between the richest fourth and poorest fourth of Grade 5 students.

Figure 3. Differences in scores based on socioeconomic status. Source: SEA-PLM 2019 Main Regional Report (2020).

There were also significantly higher scores seen among Grade 5 students who did not repeat a grade; those who studied in schools located in areas with lots of resources (e.g., playgrounds, public libraries, cinemas); those who had positive attitudes toward school (“I like being at school” or “I feel like I belong to this school”); those whose parents were involved and supportive of their kids’ studies; and those under school principals who cited fewer hindrances in instruction (e.g., the lack of classrooms, computers, toilets).

I suggest you look at the full report. There’s a lot to learn from it – lessons that I hope education officials are taking to heart.

Are things about to get worse?

Note that the 90% learning poverty statistic was before the pandemic. It’s likely worse now because of COVID-19. But we’ve yet to see an updated international assessment. The figures are going to be even more heartbreaking.

On top of all this, the highest-ranking education officials seem to be decided on making things even worse.

Education Secretary and Vice President Sara Duterte, who recently (and only recently) admitted to having no education background, ordered that public school classrooms be stripped bare of unnecessary decorations. Some tachers followed the directive too much that they stripped their classrooms totally bare (à la North Korea).

Some education experts raised their eyebrows, saying visual aids on classroom walls do help students to some extent.

At least the Department of Education could have conducted a pilot study first, involving some schools – instead of imposing the measure nationwide in one fell swoop. This betrays the DepEd’s lack of commitment to evidence-based policymaking.

For the second straight year, Duterte is also pushing for P150-million “confidential funds” for the DepEd. Whatever for? One education undersecretary said it’s meant to protect students who might fall prey to “intel activities, recruitment” in schools.

But seriously. The DepEd never had such opaque funds before Duterte took the helm. Exactly how many students are victimized by these illicit activities, if any? And is this seriously the DepEd’s priority amid the extreme learning poverty rate?

Duterte once defended the confidential funds by saying, “Education is intertwined with national security. Napakahalaga na (It’s very important that) we mold children who are patriotic, children who will love our country, and who will defend our country.” Really?

Meanwhile, some teachers on social media are literally begging for donations (even just a few pesos) so they can repair their classrooms. Why not just pour the needless confidential funds for this purpose?

Apart from this obsession with confidential funds, Duterte has brought red-tagging to the agency, and she has branded the revised basic education curriculum the “MATATAG Curriculum” (matatag being a Filipino word that brings up notions of strength and stability and resilience).

I’m afraid to say that Sara Duterte is currently the biggest setback in our fight against learning poverty. With her militaristic tendencies in the education department, she seems bent on producing unquestioning foot soldiers for some future war against an imagined enemy, rather than independent, skilled, and critical-thinking students ready to take on the 21st century. Worse, the culture in DepEd (which, organizationally, is too centralized for its own good) allows her authoritarian tendencies to thrive.

I also blame President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who, out of political convenience and lack of concern for our students, knowingly appointed a non-educator to lead (or lead astray) the one agency tasked to deliver us from this education crisis.

Unless an actual education expert replaces Duterte in DepEd, I’m sad to say the education sector is heading to an even worse place, and the country will inevitably pay for this in decades to come. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan, PhD is an assistant professor at the UP School of Economics and the author of False Nostalgia: The Marcos “Golden Age” Myths and How to Debunk Them. JC’s views are independent of his affiliations. Follow him on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ Podcast.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINYON] Tungkol sa naging viral na social media conjecture](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-conjecture-07262024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[EDITORIAL] Apat na taon na lang Ginoong Marcos, ‘di na puwede ang papetiks-petiks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/animated-bongbong-marcos-2024-sona-day-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=280px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Delulunomics: Kailan magiging upper-middle income country ang Pilipinas?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/in-this-economy-upper-middle-income-country.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=421px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Marcos Year 2: Hilong-talilong](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/animated-bongbong-marcos-2nd-sona-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=136px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] A fighting presence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-a-fighting-presence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=441px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Rappler’s Best] Knowing when to leave](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/biden-sara-gfx.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

Firstly, thanks to Prof. JC Punongbayan for writing about our country’s

learning poverty rate, which is worth sparing a thought.

Secondly, President Marcos Jr. knowingly appointed VP Sara Duterte as DepEd Secretary not only out of political convenience but, perhaps, also out of Fear. Giving VP Sara the DND post, which she really asked for, may give her an opportunity to do what former DND Secretary Enrile did to his father. So the DepEd Secretary post was merely a “consuelo de bobo” for a mistrusted ally.

Thirdly, the recent directive that classrooms be

stripped bare of unnecesarry decorations, which may include the

photo of President Marcos Jr., may just be an indirect revenge

against President Marcos Jr. and a certain Mr. “Tambaloslos.”

Fourthly and lastly, President Marcos Jr. may not really be having a lack of concern about our students. He is, perhaps, concerned that the high Learning Poverty Rate be maintained or worsened because

this will result to the making of more “bobotantes” in the future. Take note that there are still Imee Marcos, Martin Romualdez and Sandro Marcos in the Presidential Waiting List – and all of them will need the support of future “bobotantes”!