SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Back to the future?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/09/TL-duterte-marcos-September-21-2021.jpg)

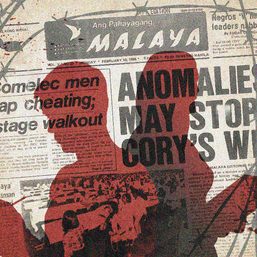

Since 1983, the 21st day of August and September have become intertwined. Thirty-eight years after the event, much still remains unknown or unverified about the murder of Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino on August 21, 1983, including the identity of the mastermind. Was Ninoy’s death inevitable? In an alternate universe, other decisions taken might have caused events to take a different turn. Few would dispute, however, that the long road to the airport assassination of Aquino began with his arrest by government forces after Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972.

Aquino had tried to preempt the move by exposing the blueprint, Operation Plan Sagittarius, in a privileged speech in the senate on September 13. His warning only accelerated the timetable. The idea of overriding term limits had already taken concrete form in July 1972, when the “Seven Wise Men” first convened (Marcos, DND Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile, PSG Chief Fabian Ver, Metrocom Chief Alfredo Montoya, Rizal PC Chief Romeo Gatan, and Eduardo Cojuangco) in Malacañang. The Wise Men gathered on the night of Ninoy’s Sagittarius speech and set September 21 as the date for the coup. On September, 14 Marcos added to the original six plotters the chiefs of the security services: AFP Chief Romeo Espino; AA Commanding Officer Rafael Zagala, PC Chief Fidel V. Ramos, PAF Chief Jose Rancudo, PN Commander Hilario Ruiz, and AFP Chief of Intelligence Ignacio Paz. Baptized the 12 Apostles or the Rolex 12, after the timepiece given to them as a presidential gift, the group planned the operational details of the constitutional coup.

Marcos won the support of the security establishment by presenting martial law and the continuity of his administration as the essential response to an existential triple threat: the communist insurgency; the Muslim secessionist movements; and the rightist elite oligarchs controlling the political opposition. He would launch a “revolution from the center” to rescue the nation.

The threat from the elite was largely fictitious. Politics had always been a game for the elite and was comfortably played within the rules of an electoral system that allowed one set of the elite to succeed each other. But it was true that the country had never faced in its history the simultaneous assault from communist dissidents and Islamic separatists. Marcos succeeded in distracting the public from his accountability for both problems.

In 1972, Marcos had been in power for seven years, the only president to win re-election for a second, four-year term. If the NPA had gained in strength, it had done so during his administration. Communist militancy mainly draws its power from the failure of government to address the social and economic concerns of the poor. To suppress a social/ideological movement, the successful counter-insurgency strategy must win “hearts and minds,” which the administrations that followed Ramon Magsaysay and the New Society failed to do.

Even clearer was the accountability for provoking the Muslim secessionist movements. Details have remained murky about the 1968 “Jabidah Massacre” of Muslim army recruits undergoing training for clandestine operations to recover the contested territory of Sabah from Malaysian control. The incident, also the subject of a Ninoy Senate speech, triggered the organization of the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM), launched by former Cotabato governor Datu Udtog Matalam in 1968. A month after the official declaration of Martial Law, a member of the short-lived MIM, member Nur Misuari established the Moro National Liberation Front.

Fast forward to 2022. We can see some progress on the three problems that Marcos used to justify martial law. Ironically, it is the government that appears ambivalent about what has been accomplished. Proclaimed a populist leader, Duterte has continued his attack on established oligarchs, even as corruption cases surging with the coronavirus, from PhilHealth to Pharmally, suggest the emergence of a new oligarchy. The work done during the Arroyo and PNoy administrations for the establishment of BARMM, eventually approved by the Duterte government, has kept a lid on the still simmering secessionist threat. Admittedly, sectarian violence, clan rivalries, competition over the island’s shadow economy, in the larger context of the uncompleted peace process between the government and the MILF, continue to afflict Mindanao. As a Mindanao president, Duterte had been expected to give the issue priority attention.

In the last decade, the most violent clashes have taken place, not against the NPA but against Islamic jihadists, counting the Zamboanga Siege in 2013, the Mamasapano Massacre in 2015, and the Marawi Occupation in 2017. And yet, in the last year of his term, Duterte is appropriating budgetary resources — where they go is not so clear — and riding roughshod over human rights concerns to end a communist insurgency that began some 90 years ago and has clearly lost steam. In 2016, Duterte was inviting Joma Sison to join his government. Having failed at the proclaimed (and impossible) mission to stop corruption and the drug trade in six years, the administration is desperate to fix a legacy achievement on its belt.

Overtaken by martial law, the 1973 presidential elections never took place. That event cast the country into a spiral of sporadic violence and aborted reforms that lasted over 30 years. As in 1972, we are again gearing up for presidential elections. The incumbent president, against the intent of the Constitution, seeks to retain national office, hoping to gain immunity for criminal charges that may await him at the end of his term. This was even before the decision of the International Criminal Court to begin investigation on charges of extrajudicial killing of suspected drug dealers perpetrated during his administration.

While internal security threats persist, they pose less of a clear and present danger than in 1972. Still, with the pandemic and the challenge presented by China in the WPS, the stakes are high in the 2022 elections, for Duterte and the country. Now is an opportune time to review and to reconsider the lessons of 1972. – Rappler.com

Edilberto de Jesus is a senior research fellow at the Ateneo School of Government.

Voices features opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Bridging memory and hope in the run-up to 2022](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/08/TL-remembering-run-up-to-2022-1280.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[ANALYSIS] Attempts to retain power and the election system](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/06/Opinion-June-11-2021-01-sq.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[WATCH] In The Public Square with John Nery: Preloaded elections?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/04/In-the-Public-Square-LS-SQ.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Newspoint] 19 million reasons](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/12/Newspoint-19-million-reasons-December-31-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=181px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[OPINION] The long revolution: Voices from the ground](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/06/Long-revolution-June-30-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=239px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] I was called a ‘terrorist supporter’ while observing the Philippine elections](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/06/RT-poster-blurred.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] Improbable vote](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/03/Newspoint-improbable-vote-March-24-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=339px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[New School] Tama na kayo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-tama-na-kayo-feb-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=290px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Only IN Hollywood] After a thousand cuts, and so it begins for Ramona Diaz and Maria Ressa](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/Leni-18.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=262px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] The lucky one](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/lucky-one-april-18-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=536px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Just Saying] Marcos: A flat response, a missed opportunity](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcos-flat-response-april-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] Hitting rock bottom](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/Newspoint-hitting-rock-bottom-December-2-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=283px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] The Ninoy constituency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/TL-Ninoy-constituency-August-25-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=334px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.