SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] The Cold War’s nuclear weapons tests, and the damage and waste they left behind](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/05/Screen-Shot-2022-05-19-at-1.06.30-PM.png)

The following is the 32nd in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

During the “Cold War” following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union raced to develop nuclear weapons. The US chose the Marshalls as the ideal place for testing nuclear bombs, considering them isolated, sparsely populated, and far from its own shores. How this would affect the indigenous people was hardly a consideration.

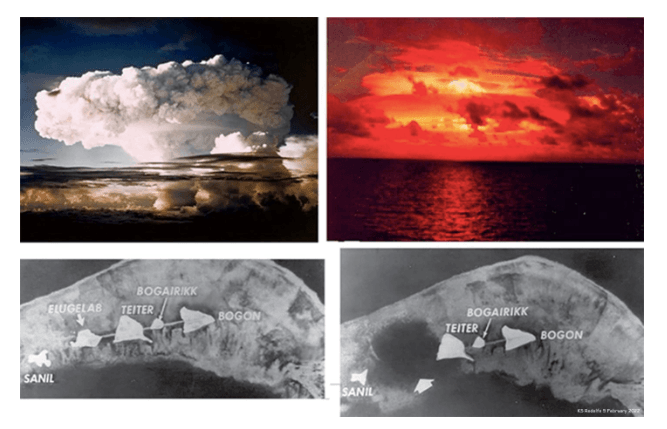

The first nuclear tests began in 1946 on Bikini Atoll and continued there until the notorious hydrogen bomb Test Bravo in 1954. Expected to yield the explosive equivalent of six million tons of TNT, Bravo made 15 million instead, surprising its designers.

Unusually, the winds were blowing eastward. Meteorologists warned that many people were living downwind, but for bureaucratic reasons Bravo was held anyway. On Rongelap Atoll 190 kilometers away, finely powdered radioactive coral fell like white snow. Children played with it, ate it. They, and Japanese fishermen on a ship 135 kilometers away, suffered serious radiation illnesses.

And so, because Enewetak Atoll is more remote than Bikini, the remaining tests were held there – in the end, twice as many tests as those on Bikini. But people remain much more familiar with “Bikini” because of the swimwear named after it.

I can’t resist remarking that the swimwear totally contradicts the traditional Marshallese sense of modesty. Men and women usually went bare from the waist up, but wore wraps to conceal their genitals and thighs.

In December 1947, to prepare for the Enewetak tests ,all the 145 dri Enewetak and dri Enjebi fisherfolk and subsistence farmers were forcibly relocated to Ujelang Atoll, some 250 kilometers to the southwest. Government records say nothing about what the people felt about the move. But, like Filipinos, Micronesians are very strongly attached to their homeplace.

From 1948 to 1958, 43 nuclear tests were fired on Enewetak islands. “Ivy Mike”, the world’s first true hydrogen bomb, was on November 1, 1952. Yielding the energy of more than 10 million tons of TNT, it totally obliterated Elugelab Island, along with parts of Sanil and Teiter islands, leaving a crater 1,150 meters wide and 50 meters deep. That hole is so big you can see it in the small-scale map of Enewetak above.

Watch Ivy Mike explode in this video, taken six kilometers away judging from the time lag between the explosion flash and its sound.

It is shocking that such extravagantly powerful weapons were being exploded while nuclear physics was still such a raw, new science. In Ivy Mike’s fallout debris, physicists discovered two new, artificial heavy elements that they named Einsteinium and Fermium after two of their own heroes. They also found two new plutonium isotopes, Pu244 and Pu246.

In 1958, a nuclear moratorium with the USSR was about to go into effect. To beat the deadline the US rushed to make 22 final tests. Runit Island was the site of 11 of them. Strangely enough, as we will see, “Runit” means “go through the pit” in Marshallese.

One of these tests, “Cactus” on May 6, yielded 18 kilotons, about as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb. It blasted out a crater 360 feet wide and 30 feet deep on the north end of Runit, close to a shallow underwater crater of roughly the same size that the Lacrosse test had made two years earlier.

Made into a domed repository for nuclear waste, Cactus Crater was central to the clumsy efforts of the US government to clean up after the nuclear tests. The efforts would be laughable, if so many people had not suffered from them. The Ivy Mike video explores it also.

After the last tests in 1958, there was no urgency to clean up the gigantic radioactive mess on Enewetak. Only in 1972 and 1973 was the radiologic state of the atoll surveyed. And only after another four years did efforts to deal with the waste finally begin.

Fine plutonium dust had contaminated all of Runit. Plutonium 239, its most important isotope, has a half-life of 24,100 years and can cause cancer centuries later if even tiny amounts are inhaled or ingested. The radiologic survey indicated that the island would remain toxic and unlivable practically forever. Government scientists agreed that other islands might eventually be made habitable, so federal officials decided to sacrifice Runit by collecting the radioactive debris on it, Enjebi and the three other Enewetak test-site islands, and dumping all of it into the Cactus crater.

The government estimated that using private contractors, specialist nuclear workers for the cleanup, would cost $40 million. “Too much!” Congress said; military troops would do the work instead. Therein lies a very sad story of how badly a government and its military can treat even their own people.

How the cleanup troops were screwed

From 1967 to 1970, almost 6,000 American military personnel each spent a six-month tour of duty on Enewetak, scraping about 73,000 cubic meters of contaminated soil and debris from the five other islands that had been used for tests and bringing them to Cactus Crater on Runit Island. Six of them died in accidents, but more importantly, simply to save money they were never told about how dangerously radioactive the stuff was. Records that were declassified in the 1990s clearly document this.

Respirators and other protective equipment were missing or unusable. Cheap safety monitoring systems failed. Officials lied to concerned members of Congress by falsely claiming nonexistent safeguards. They also told the troops that the islands emitted no more radiation than dental X-rays, while privately worrying among themselves about “plutonium problems” and “highly radiologically contaminated” areas.

When one Air Force radiation technician arrived at Enewetak Atoll in 1979, public relations personnel dressed him in a yellow suit and respirator, photographed and videoed him, then took the suit and respirator back. He wore only cutoff shorts and a sun hat during his months of cleanup.

Many of the hundreds of cleanup troops now have brittle bones, cancer, and children with birth defects. A social media survey among more than 400 Enewetak cleanup veterans found that 20% among them have cancers of some type. Many have already died; others are too sick to work. Veterans who worked in the southern part of the atoll have very few such health issues.

For a long time, the military denied any connection between these illnesses and the cleanup, claiming radiation exposure well below recommended thresholds, based on defective or intentionally false radiation monitoring.

In 1990 the US Congress recognized that radiation on Enewetak during the atomic tests in the 1950s had harmed troops stationed nearby, who deserved to be compensated. It passed a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, but the cleanup troops were not covered. To correct this, another congressional bill was filed in 2019; if passed, victims or their living heirs can claim $75,000 in compensation.

A paltry sum, considering what all the troops underwent and how badly they were treated.

Our next foray looks at how the waste was stored in the Runit Dome, and what has happened to the dome since. – Rappler.com

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Keep posted on Rappler for the next installment of Rodolfo’s series.

Previous pieces from Tilting at the Monster of Morong:

- [OPINION] Tilting at the Monster of Morong

- [OPINION] Mount Natib and her sisters

- [OPINION] Sear, kill, obliterate: On pyroclastic flows and surges

- [OPINION] Beneath the waters of Subic Bay an old pyroclastic-flow deposit, and many faults

- [OPINION] Propaganda about faulting, earthquakes, and the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Discovering the Lubao Fault

- [OPINION] The Lubao Fault at BNPP, and the volcanic threats there

- [OPINION] How Natib volcano and her 2 sisters came to be

- [OPINION] More BNPP threats: A Manila Trench megathrust earthquake and its tsunamis

- [OPINION] Shoddy, shoddy, shoddy: How they built the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Where, oh where, would BNPP’s fuel come from?

- [OPINION] ‘Megatons to Megawatts’: Prices and true costs of nuclear energy

- [OPINION] Uranium enrichment for energy leads to enrichment for weapons

- [OPINION] Introducing the nuclear fuel cycle

- [OPINION] On uranium mining and milling

- [OPINION] Enriching and fabricating BNPP’s uranium fuel

- [OPINION] Decommissioning BNPP, and storing the nuclear dragon’s radioactive manure

- [OPINION] So how much greenhouse gas does nuclear power really generate?

- [OPINION] Getting up close and personal with the atom, and its nucleus that powers NPPs

- [OPINION] The nucleus and isotopes: Why BNPP needs Uranium 235, Not Uranium 238

- [OPINION] What you should know about radioactivity

- [OPINION] Uranium mine waste and the weird idea of half-life

- [OPINION] How nuclear power plants work: Hot monster piss from Morong

- [OPINION] What if there was a spent-fuel pool accident at the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant?

- [OPINION] Nuclear weaponry, its radiation, and human health

- [OPINION] What Chernobyl could have taught us, but hasn’t been allowed to

- [OPINION] Activating BNPP would give cancer to workers and adults living nearby

- [OPINION] Activate BNPP? You could increase childhood cancers in Bataan and beyond

- [OPINION] The Hanford Site: Where nuclear pollution began and still reigns

- [OPINION] Enewetak, Paradise Lost: Enewetak and its people

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Who decides whether Bataan should go nuclear?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/imho-bataan-nuclear-powerplant.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=271px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Nuclear energy should not become major part of Philippine energy system](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/nuclear-energy-january-26-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=205px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.