SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BAGUIO, Philippines – In early September 2019, Tropical Depression Kabayan (Kajiki), Typhoon Liwayway (Lingling) and Tropical Storm Faxai became active east of the Philippines.

As they headed towards the country, a meme started to spread on social media. “Inilagay ng Diyos ang (God put in place the) Sierra Madre Mountain Range to protect us from typhoons,” it read, showing the mountain range on the side and using the hashtags #SaveSierra and #NotoMining. “Let us all help by simply sharing this campaign information.”

The meme became viral. Of the three, only Typhoon Liwayway affected the Philippines. It enhanced the southwest monsoon, caused floods in extreme Northern Luzon, and caused relatively mild agricultural damage of about P5.65 million in Pampanga.

Liwayway or Lingling wreaked havoc in Japan, South and North Korea, China, and even Russia, killing eight people and causing P300-million damage to property.

The third one, Tropical Storm Faxai, did not enter the Philippine area of responsibility. It became one of the strongest typhoons to hit Japan, resulting in three fatalities and $10 billion in damage.

Three years later, in September 2022, the meme resurfaced when Super Typhoon Karding (Noru) made landfall, hitting the Sierra Madre in Quezon province.

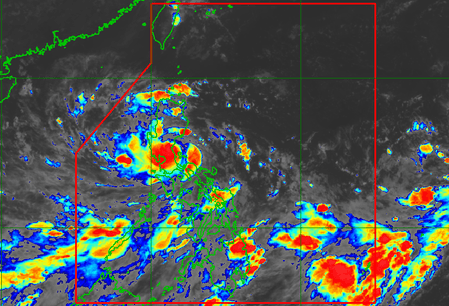

“The Sierra Madre mountain range doing her thing,” went one post that social media users retweeted 3,500 times. It showed what it claimed was a Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) image from a weather tracking station, showing Karding about to hit Sierra Madre.

Karding lived up to its super typhoon status. The strongest Philippine typhoon of 2022 killed 40 people. The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council reported more than P300 million in infrastructure damage and over P3 billion in agricultural damage.

When Karding made its first landfall over the Polillo Islands at 3:30 pm on September 25, 2022, it was a Category 4 typhoon with a peak intensity of 177 kilometers per hour. After hitting Polillo and the Sierra Madre, it weakened to the point that it disappeared from multispectral satellite imaging.

It emerged again from Zambales as a Category-2 typhoon at 5 pm of the following day.

‘Backbone of Luzon’

The Sierra Madre is often referred to as the backbone of Luzon. It resembles a huge spine stretching across the entire eastern side the Philippines’ main island. The longest mountain range in the country, it spans 10 provinces in the Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon, and the Calabarzon.

With a total length of 600 kilometers and a maximum elevation of 1,500 meters, the Sierra Madre presents an imposing landscape. Despite appearing as a continuous wall of mountains, it is divided into northern and southern segments by the Philippine Fault near Dingalan Bay.

In 2022, apparently to generate media attention surrounding the Sierra Madre, memes peddling false information surfaced, even outrageously claiming that the Marcoses built the Sierra Madre.

The Sierra Madre was formed 20 million years ago by the Pacific plate, integrating the archipelago into the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Aside from the Sierra Madre, another mountain range formed by the Pacific plate is the Cordillera Central, which extends 300 kilometers in length and 90 kilometers in width. It runs along the western side of Luzon, reaching maximum elevations of about 3,000 meters. Although the Sierra Madre is twice as long as the Cordillera, it is only half as tall.

Connecting the Cordillera to the north with the Sierra Madre to the east are the Caraballo Mountains. Together, these three mountain ranges form the catchment basin known as the Cagayan River Valley, the second-largest expanse of flatland in the Philippines.

What science says

So, can these mountain ranges bring typhoons, even super typhoons, to their knees?

Two young Filipino climate scientists – Dr. Gerry Bagtasa and Dr. Bernard Alan B. Racoma – decided to answer the question in their study, “Does the Sierra Madre Mountain Range in Luzon Act as a Barrier to Typhoons?,” published by the Philippine Journal of Science in January.

Bagtasa is a professor from the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology at the University of the Philippines-Diliman. Racoma – also of IESM and UP Diliman’s most outstanding PhD graduate this year – is connected with the University of Reading in the United Kingdom.

The study, supported by the Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development, followed the tracks of tropical cyclones that passed through the Sierra Madre.

Their study pointed out that it is a scientific fact that cyclones that make landfall weaken, and that typhoons should not be seen as a chaotic punishment from the gods, as the Sierra Madre legend would have it, but in more physics terms.

In the Philippines, a broad zone of low pressure exists on either side of the equator: the northeast trade winds (known as amihan) and the southeast trade winds (habagat).

Within these trade winds, air heats up over the warm tropical ocean, leading to the formation of thundery showers. When these showers rapidly grow into large clusters, they often develop into a depression with a center of low pressure at the surface.

At times, these depressions evolve into typhoons as the increased strength of the trade winds, and the accelerating spiraling winds inward and upward, release heat and moisture. The intensity (maximum horizontal wind) at the surface can reach almost 170-kph.

Intensity and strength define typhoons. The Hongkong Observatory states that in accurately assessing the intensity of a tropical cyclone, the best way is to collect and analyze the wind speed information near the center of the storm. It is difficult to measure that when a weather formation is still far out at sea, so forecasters use satellite imagery for the D’vorak technique, which analyzes the distribution and patterns of cloud top temperatures of a tropical cyclone, and incorporating these with statistical data summarizedthrough a number of years.

A typhoon’s momentum is disrupted when it makes landfall.

“Dissipation due to surface frictional loss, especially in the boundary layer with rugged terrain like mountain ranges, reduces the inflow of angular momentum, thus prohibiting its conservation. This process weakens the maximum and/or tangential winds associated with TCs (tropical cyclones),” part of the study read. They referred to this as the decay constant.

“TC intensity decreases when it interacts with land due to surface friction and the reduction of ocean heat, momentum, and moisture fluxes,” the study said.

Simulations and experiments

The two scientists said no previous study on the topic has investigated the hazard-mitigating effects of the Sierra Madre and the Cordillera ranges. So they asked: What happens if the Sierra Madre Mountain Ranges (SMMR) and Cordillera Mountain Range (CMR) weren’t there in the first place?

For the research, they used the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model for simulations. The model is a non-hydrostatic numerical weather prediction model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and widely used for atmospheric research and operational forecasting.

Bagtasa and Racoma ran 45 tropical cyclones that passed through these ranges from 2000 to 2020 through the WRF. Each simulation started two and a half days before landfall and two and a half days after, “with one day allotted for the model spin-up.”

The tropical cyclone simulation began with Typhoon Seniang or Bebinca in November 2000 and continued until Noru or Karding. Most were typhoons, while six were severe tropical storms, and four were tropical storms.

They conducted three numerical experiments using the WRF.

“The first experiment is the control (CTRL) run where the model terrain was unmodified. The second and third experimental runs used a terrain with flattened SMMR and CMR, respectively,” the study said.

In the second and third models, it was as if the two mountain ranges never existed. However, this was done to answer the question of whether they indeed have a dramatic effect in protecting the rest of Luzon from typhoons.

It depends

Does the SMMR and the Cordillera Mountain Range in Luzon act as a barrier to typhoons? Bagtasa and Racoma said it depends on the hazard involved and the location in question.

One of the more surprising results in the simulations was that, with or without the Sierra Madre and the Cordilleras, the intensity of the tropical cyclones did not weaken during the first six hours on land.

However, the Cordillera limits the re-intensification of the typhoons emerging from land and moving westward over the West Philippine Sea.

“In addition, both the SMMR and CMR slightly slow down the translational speeds of TCs before and at landfall, which means that the mountains’ presence may be able to increase the exposure duration to TC hazards such as wind and rain,” it added.

The scientists also noted the typhoons that passed through both mountain ranges, as well as those that passed only through the Sierra Madre and Central Luzon, and those that passed through the southern end of the Sierra Madre toward the relatively flat Southern Luzon area.

They found that the Sierra Madre reduces wind field strength more uniformly across Luzon, partly due to its extensive length covering almost the entire eastern Luzon.

“The SMMR has the most significant mitigating potential for the island of Catanduanes and the southeastern parts of Bicol in the case of TCs traversing the southern Luzon region,” they wrote.

The study found that Sierra Madre reduces wind hazard exposure from 1% to 13%.

Cordillera at its summit reduces wind exposure to up to 10%. Cordillera also shows a higher weakening effect in terms of AWE or accumulated TC wind-field energy for Cagayan Valley and in the western and Central Luzon where it can reduce AWE from 8% to 30%.

‘Orographic effect’

The Sierra Madre effect on rain generation, however, is another story.

Bagtasa and Racoma together with Dr. Carlos Primo David, also of UP Diliman, published an article for the Philippine Journal of Science entitled “The Change in Rainfall from Tropical Cyclones Due to Orographic Effect of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range in Luzon, Philippines.”

The term “orographic effect” refers to variations in airflow caused by land topography that drive air upward. These alterations have the potential to disrupt the weather system.

The study showed that the leeward (the side of the mountain sheltered by the wind) and the windward (the side facing the storm) shift depending on the location of the tropical cyclone.

“At the moment where the TC hits the mountain range, the southwest and the northeast portions of the intersection between the center of the storm and the mountain range becomes the windward side, hence increasing precipitation in those general areas,” the study said.

This is in contrast to the storm direction, in which winds to the south of the storm direction are going in the opposite direction of the storm.

“This is contradictory as well with the idea of SMMR blocking rainfall associated with TCs coming from the East, as the TC in fact brings in more rain along the southwestern areas of the mountain range due to the reversed flow of winds,” the study added.

More rain as they linger

The Sierra Madre also slows down typhoons causing them to generate more rain as they linger.

“Were it not for the increased rainfall due to the orographic effect caused by the SMMR, flooding would probably have not occurred during the storms TS Ondoy, TY Labuyo, and TS Mario in Metro Manila,” the study said.

The latter study by Bagtasa and Racoma expounded on these.

“In terms of rainfall, SMMR increases rainfall along its western slopes from 23-48 percent (and from 25-55 percent in Metro Manila) and reduces rainfall in Cagayan Valley by 10-59 percent, especially on the eastern slopes of the CMR as the SMMR serves to block the westward moisture flow,” the study said.

The orographic effect of the Cordillera is relatively constrained to its immediate slopes where the rainfall increases by more than half (58%).

Without the Sierra Madre and Cordillera, most of Luzon would be drier except for Cagayan Valley, which is sheltered by Sierra Madre from winds and rains.

But how comforting would it be for Metro Manila, for example, if the Sierra Madre could reduce the wind velocity of typhoons by 3% to 8% but enhance rainfall threat by more than half?

“Therefore, with the consideration that more TC-induced damages are water-related and not due to wind, relying on mountain ranges as barriers to TCs is flawed, inaccurate, and potentially dangerous as this may lead to complacency,” the study said. – Rappler.com

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] Willful indifference](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/np-willful-indifference-05032024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=270px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.