SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

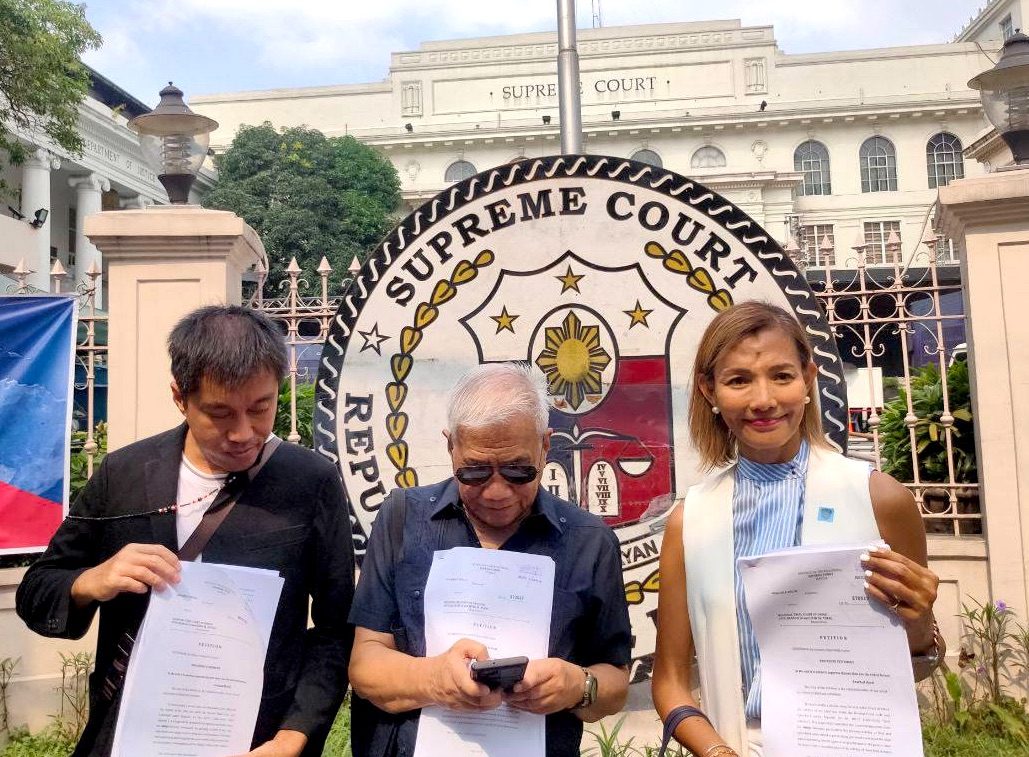

MANILA, Philippines – Activist and former lawmaker Walden Bello filed a petition before the Supreme Court on Tuesday, December 5, essentially asking the Supreme Court to decriminalize libel in the Philippines.

“Petitioner respectfully prays that the present Petition be granted declaring unconstitutional Articles 353 to 355 of the Revised Penal Code as well and Section 4(c)(4) of Republic Act No. 10175 on Cyberlibel for being violative of Section 4, Article III of the Bill of Rights and nullifying and permanently enjoining the prosecution of petitioner under the said laws,” said the petition, prepared by Bello’s lawyer Estrella Elamparo and the Union of Peoples’ Lawyers in Mindanao in Davao.

While Bello’s petition is asking the Supreme Court to nullify all of Philippine criminal laws on libel, the country’s civil code still says that a civil action may still be filed in cases of defamation, completely independent from criminal prosecution. Civil cases mean the aggrieved party can ask for damages, as opposed to criminal libel that can jail convicted people.

“Although net effect is if they’re declared unconstitutional, libel ceases to be a crime. [It] still may carry civil liability under Article 33 of the Civil Code for damages,” Bello’s lawyer Elamparo told Rappler in a message.

‘It’s high time’

Bello, who was a vice presidential candidate in the 2022 elections, is on trial and free on bail for two counts of cyber libel filed against him by Jefry Tupas, the former city information officer of then mayor and now Vice President Sara Duterte. The charges stem from Bello’s Facebook post during the 2022 campaign chiding Duterte for snubbing the debates, and mentioning there that Tupas was “snorting P1.5 million worth of drugs on November 6, 2021.” Tupas was at a beach party in Davao de Oro that was raided and caught with P1.5 million worth of drugs. Tupas said she had already left the party when it was raided.

“Petitioner was, at that time, also running for the post of Vice-President and was very clearly making a political statement when he mentioned that the trusted aide of his political opponent was reportedly caught by authorities during a drug operation,” said Bello.

“It was very clearly an expression of dissent and criticism against an incumbent official who was running for the second highest office of the land. And yet, such expression of dissent gave rise to his indictment, arrest, incarceration, and ongoing trial for cyberlibel,” he added.

Bello said that it’s “high time” that the Supreme Court removes criminal libel from Philippine laws.

The Court was already asked to do so in 2012, when free speech advocates challenged the Aquino-time cybercrime law. In that case, known as the Disini vs Secretary of Justice case, the Supreme Court fraughtly upheld the constitutionality of cyber libel, which retained the definition of ordinary libel but for internet content.

Libel, as defined by the 1930s Revised Penal Code, assumes automatic malice in a defamatory post or statement, even if the content proves to be true. This principle is called “malice in law.” It also only protects free speech in a very limited condition: that it is a straight report on a public statement (does not apply for confidential proceedings) that do not include comments or remarks.

This strict limitations have been condemned by advocates who argue that democracy will be vibrant if there is sufficient space for dissent, and a space to be wrong when you’re proven not to have disregarded truth and not utterly malicious. This inquiry into intent, and methods, is a principle called “malice in fact.”

In the 2012 Disini case, some justices wanted to already strike down libel as unconstitutional, while others like retired senior justice Antonio Carpio would have at least wanted for our libel laws to follow the “malice in fact” principle.

“While the text of Article 354 has remained intact since the Code’s enactment in 1930, constitutional rights have rapidly expanded since the latter half of the last century, owing to expansive judicial interpretations of broadly worded constitutional guarantees such as the Free Speech Clause,” Carpio said in his opinion to the 2012 Disini case.

Libel is among the pre-war laws that did not change even as the country amended and repealed laws after the restoration of democracy in 1986.

“It is high time, after a decade of the Disini doctrine, for the Honorable Court to strike down as unconstitutional the libel statutes and permanently prohibit and enjoin the prosecution of the case with the respondent court. Said laws have not achieved their legislative intents but instead have been weaponized to suppress fundamental Constitutional rights,” said Bello’s petition.

Philippines is one of 160 countries which still treat libel as a crime, as United Nations supports decriminalization.

‘Decriminalize libel’

The Supreme Court in 2012 did not only affirm libel, they also increased the penalty of cyber libel by one degree higher. That meant longer jail time, and had an effect of increasing prescription period, or the period by which one is allowed to file a libel suit after publication, from only one year to now 15 years.

Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and former researcher Reynaldo Santos was the test case for the increased libel shelf life, condemned as a threat to the free press by media groups all over the world. Ressa and Santos have appealed their conviction to the Supreme Court.

But through time, the Supreme Court has decided cases where the Court deviated from the malice in law principle, to apply the malice in fact principle, as Carpio advocated for before. Its last notable libel case was just this year where the Court also explicitly nudged judges to opt for a fine, instead of jail time, highlighting that the language of the current laws did not make jail time mandatory because of the use of the word “or” in ‘prisontime or fine.’

In 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Committee issued a non-binding resolution that Philippines’ criminal libel laws violate the country’s obligation to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which protects free speech.

The 1987 Constitution also guarantees that no law should abridge free speech and the free press.

“No freedom is absolute indeed but, given how the libel statutes have been weaponized to suppress political dissent, thereby producing the chilling effect that our Constitution has always sought to avert, it is respectfully submitted that maintaining libel/cyberlibel as crimes runs afoul with the Constitution,” said Bello.

“We have adequate legal remedies under our civil laws and procedure to curb such wrongdoing, no matter how grave it may be,” the petition added.

There is a resolution in the Senate filed by opposition senator Risa Hontiveros to decriminalize libel.

Data earlier obtained by Rappler also showed that the government has lost a third of the cyber libel cases filed since 2012, raising the argument of wastage of resources on the part of the prosecution team. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] Ted Failon, press freedom, and the Supreme Court](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240709-ted-failon-press-freedom-supreme-court.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=296px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.