SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is yet to make good his promise of respecting human rights and giving justice to victims of state abuses more than a year and a half into his administration.

The Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights) said that “not much has changed for the better” even as Marcos tried to shift away from his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte’s “macho posturing.”

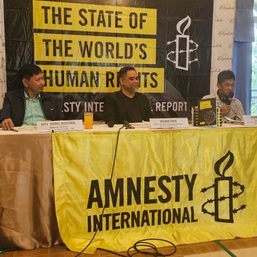

“With Marcos’ ascent to power, the promise of a shift from [Duterte]’s violent legacy remains unfulfilled,” PhilRights executive director Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan said during launch of the group’s 2023 human rights report on Thursday, December 7.

Duterte left office in 2022 with a bloody trail, mostly due to the killings under his flagship war on drugs. Data show at least 6,252 people were killed in police anti-drug operations by May 31, 2022, while rights groups estimate the number to reach 30,000 to include those killed vigilante-style. Documents obtained by Rappler, however, show that 7,884 drug suspects were killed in police operations by August 31, 2020.

The bloodbath continues well into the Marcos administration. At least 482 drug-related killings were recorded from July 1, 2022, to November 30, 2023, according to the Dahas Project of the University of the Philippines’ Third World Studies Center.

Meanwhile, rights group Karapatan also documented at least 87 extrajudicial killings as part of the counter-insurgency campaign under Marcos, as well as 12 victims of enforced disappearances and at least 316 victims of illegal and arbitrary arrest, among others.

Only three cases have led to a conviction seven years after Duterte waged his violent drug war, and more than a year into the Marcos presidency. Families of drug war victims are pinning their hopes on the International Criminal Court (ICC), even as they continue to face harassment from police, with many reporting being pressured into signing waivers that say they will not pursue legal cases anymore.

In May 2023, Rappler reported that families were asked to sign waivers, with PhilRights documenting at least 13 families who experienced the same over the years.

According to Simbulan, the reality on the ground continues to cast “shadows on any pretense of accountability and respect for human rights.” The current administration, she added, has adopted the Duterte regime’s “lack of concern” for exacting accountability.

Support the ICC investigation

The ICC is currently investigating the killings under Duterte’s nationwide drug war and the alleged killings carried out by the so-called Davao Death Squad during his watch as mayor. The proceedings have reached a level where the next possible stage could be for Prosecutor Karim Khan to either request an arrest warrant or summons if there are enough grounds.

In recent months, the Marcos administration and allies have changed their tune regarding the international court, veering away from the aversion seen during the Duterte years. More lawmakers have urged the government to cooperate with the ICC. Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla has said that cooperation with the ICC needs “serious study,” while Marcos himself said that rejoining the ICC is being studied.

Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra, who was Duterte’s justice secretary, also now does “not see any reason why [the ICC] should be prevented from coming in.”

But families and advocates are wary that things can change, and that possible openness to the ICC is still built on shaky grounds.

For PhilRights’ Simbulan, Marcos needs to be “firm and consistent” with his positions. These can be shown through the “mobilization of various agencies,” and the creation of a body that can provide assistance to the ICC and families who have filed complaints.

“If you create a structure or body to lend support and assistance both to the ICC, you should provide a budget,” she said.

“That’s one indicator that the government is indeed serious and sincere in its pronouncements to open our doors to the unhampered investigations to be conducted by the ICC,” Simbulan added.

Still, human rights groups vowed to continue engaging with stakeholders, including the government, to ensure that policies are enacted with the welfare of victims in mind.

“Hindi sapat ang galit,” Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates secretary-general Rommel Yamzon said. “Patuloy ang hakbang namin na i-engage ang gobyerno sa lobbying para ipakita ang sinseridad ng community.”

(Anger is not enough. We will continue engaging with the government and lobbying to show the sincerity of the community.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] In the Philippines, the fight for the climate is a fight against state violence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/imho-contexualizing-state-violence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=265px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.