SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

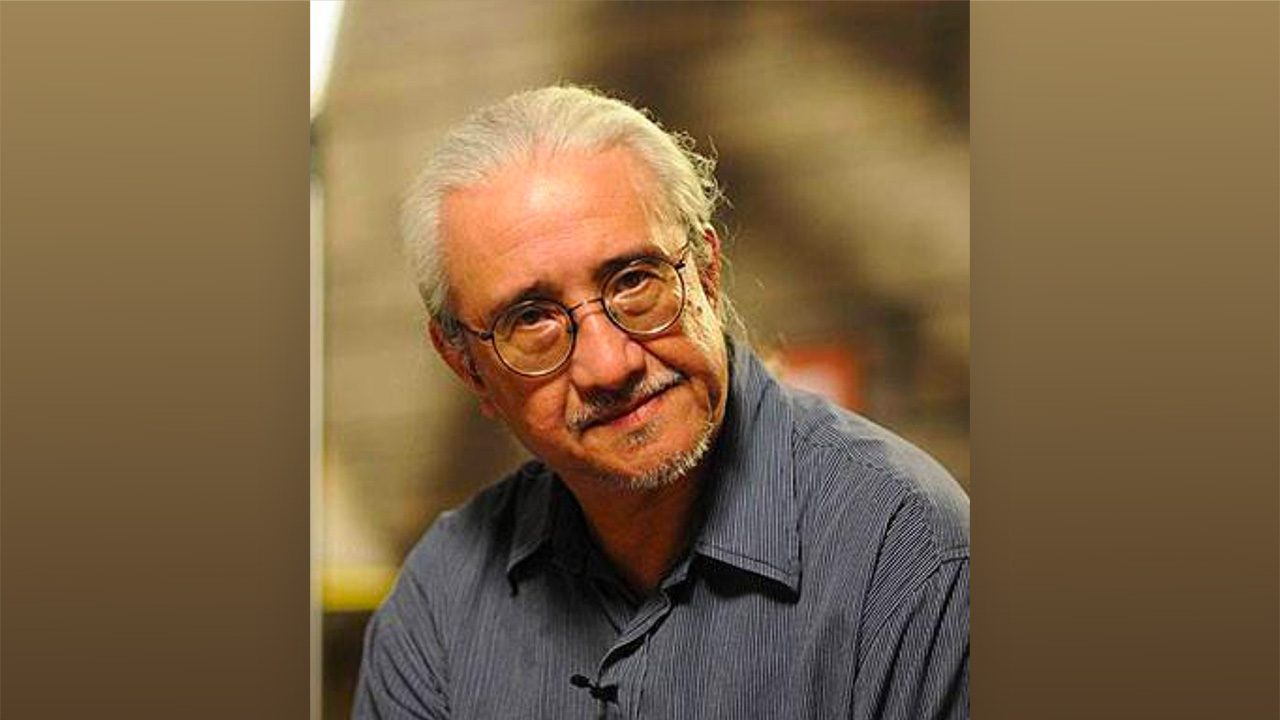

MANILA, Philippines – Conrado de Quiros is a name that, I like to assume, is known to us.

He was highly visible, after all, from 1991 to 2014 – or a good 23 years, once writing five days a week before shifting to four days a week, through all four weeks of a month of every year, without fail – as he racked up his column, “There’s the Rub,” in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, at a time when among media platforms newspapers enjoyed the biggest respect.

No wonder his fans, as it goes, were legion.

The Inquirer’s own young reporters were fans.

Unashamedly “kikay” – as veteran columnist Ceres Doyo says playfully – one of them, Juliet Javellana, now the paper’s associate publisher, recalls that when Conrad was going to be at the Inquirer building for a meeting or a talk (as columnist, he was free to send pieces from wherever he was, including from out of the country), the girls would go to the parlor first and have their “beauty fix.”

Publisher Karina Bolasco, after noting how Conrad’s young readers were cutting out his columns, and thereafter clipping, pasting, and sticking them onto notebooks, cartolinas, and clear books because, well, they wanted to write like him, sought him out as author.

And so came the first, Flowers from the Rubble, and the second, Dance of the Dunces, both anthologies of his commentaries that even changing times and tastes and technology have not diminished.

A believer, I was the self-assigned project manager for both books.

Such was the craze for his hard-hitting, often political, writing that the books just had to get done. Suddenly, ponderous subjects weren’t so boring when he subverted them with wit and humor and served them up in prose that gave gruff thoughts a surprising civility.

Likewise, it was a welcome treat to start the morning with his cunning turns of phrases, superior English, irreverent only-in-the-Pilipins anecdotes, and thickets of political gossip – the lot of it coming off as quite literary.

The fellow was just, as tiring as it is to keep saying so, brilliant.

Another book, Tongues on Fire, is a slim collection of speeches. After being invited so regularly as guest speaker in graduations, inaugurations, anniversaries in Metro Manila and the provinces, he had enough to fill a book, the more timeless of which he selected for publication.

Of course, being famous, he can also be found in many another author’s book to which he could not refuse pleas for prologues and epilogues.

One such book is 2012’s Not On Our Watch. Martial law really happened. We were there.

I am editor of that one, and as is often the case when I take on the editor’s job, I run out of writing time. Miserably close to printing date, I still had no book introduction.

I turned to Conrad. I knew the fellow was swamped with his, at the time, four-times-a-week column writing, interminable speaking engagements, high-profile meetings with political sources, and habitual visits to music dives, but, well, there was no one else I knew that could write very fast, very well, and for free!

Yes, we never talked money.

Friendship since 1971

Between us, we knew, from a friendship that began in 1971, that if I could produce money, he’d be paid for sure, but that if I couldn’t, it was what it was. Not On Our Watch happened to be a book that another set of friends wanted to contribute to Martial-Law literature, and we knew, as Conrad did, that no one would be earning from it.

What we talked about instead was theme and intent.

Within days, I got my intro.

A loose extract: “I was invited to the late great NU on a September 21 to talk a bit about Martial Law. The calls streamed back and forth. The youth were particularly fascinated by the lifestyle of their counterparts during Martial Law. Particularly by the midnight curfew…

“What disturbed me, however, was quite a number of callers wondering what was so wrong with martial law. They had heard from their parents and/or other ‘oldies’ that people were disciplined during that time, rice was cheap, gasoline was cheap, movies were cheap, the poor were less poor, life was generally easier.

“I said that was true in part. But underneath that lay one of the greatest deceptions of Martial Law. If art, as Picasso said, was the lie that revealed the truth, then Martial Law was the truth that revealed the lie. True enough, food was more plentiful then, things were much cheaper then, inflation wasn’t rife then. But all that was paid for by the sacrifice of future generations.

“Specifically, all that was paid for with the billions of dollars in loans Ferdinand E. Marcos got from foreign banks, much of which he, his family, and his cronies stole. Which debt doomed future generations to servitude: Which debt we are paying for now. Which debt our children and their children will be paying for tomorrow.

“Martial Law robbed this country of its wealth: It was during that time that this country’s forests disappeared.

“Martial Law robbed this country of many of its best and brightest: It was during that time that the youth who had taken to the hills were killed.

“Martial Law robbed this country of its future: It was during that time that the country embarked on the path to becoming the sick man of Asia, subsequently to be left behind while the rest of the continent advanced.”

The rest of the ten-page intro, let me assure you, is as riveting.

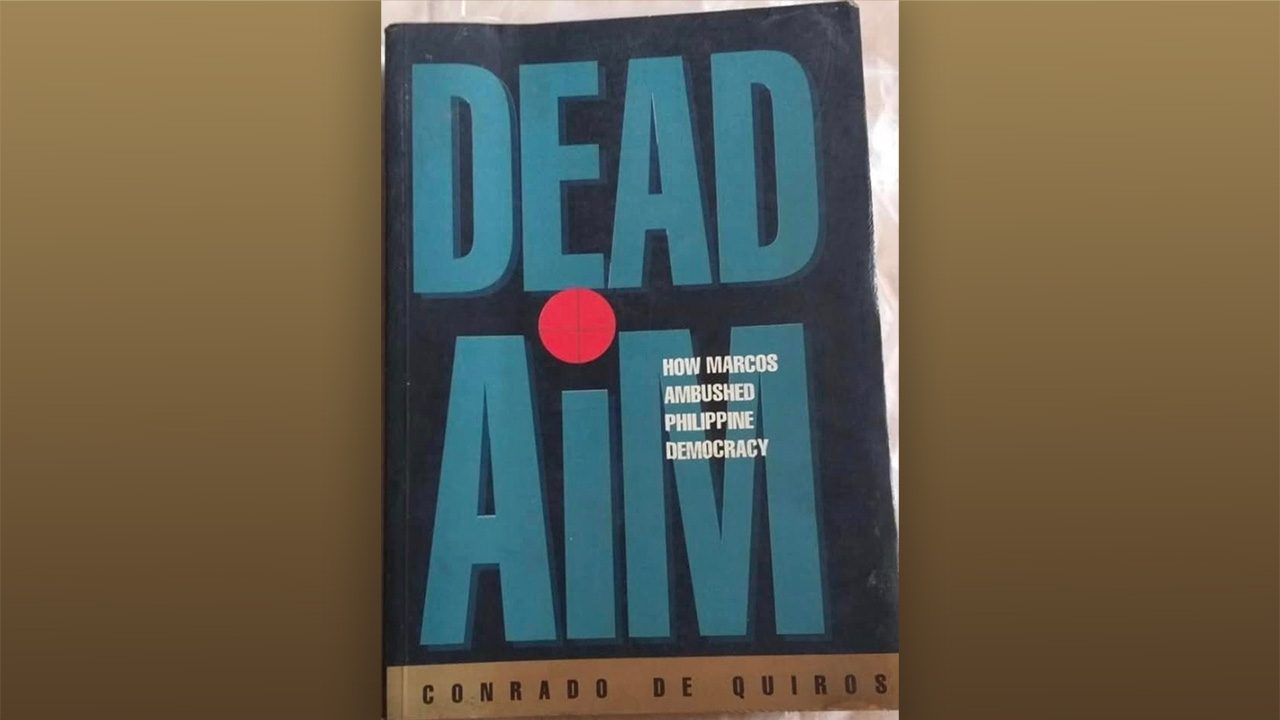

And then there is his magnum opus: Dead Aim. How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy.

A grand book, with publisher Eugenia Apostol its grand dame, Dead Aim is 444 pages replete with facts and figures, interpretation and analysis, past history and current events, highlights, sidelights, insights – all of which read in the end, as always with Conrad, like fine literature.

In his acknowledgment page, listing people who made the book possible, he wrote me up first, saying: “Jo-Ann Maglipon, whose faith moved mountains, gods, and Eugenia Apostol, in that ascending order of difficulty.”

A believer, I was the self-assigned prime mover of that major book that he produced even as he was producing his columns no fail, running an NGO serving the media needs of NGOs, accepting speaking invites, meeting with insider sources, and having his fix, if no longer nightly, of music dives.

No, we never talked money.

Between us, we knew that if he could produce it, I’d be paid for sure, but that if he couldn’t, it was what it was.

That was 1997, it is 2023, and I remember it all.

I headed a small team that barrelled past the stumbling blocks: research, fact-checks, interviews, encoding, copyediting, proofreading; past the cheerless nights when hours were never enough and daytime always came too soon, along with everybody’s daily job demands; past the physical fatigue that led to lost humor, frayed patience, and snarky tongues.

But it was also a team that knew how to lap up the many fun things – the sporadic chatter and political chismis; jokes about our friend Rustie Otico’s idiosyncracies, he whose editing skills a book already this superior still welcomed; and meals that Conrad’s family prepared for us, by way of thank you, through the many overnights over many months pressing up to Dame Apostol’s dreaded deadline.

The big book is worth the big work: Dead Aim is today a classic of political and historical literature.

To those, of course, who’ve never heard of Conrad or know of him only through his works, let it be said that here was a man who was more than the sum of his writings.

He was a studious breadwinner, fierce father, supportive husband, concerned citizen, disciplined writer, and loyal friend – even to loyal friends who liked being honest and said that the fellow’s was not at all the best voice in a jam with brothers Paul and Emil, who came into the world with pretty damn good voices.

Conrad did second voice admirably, says Paul in his manoy’s defense, and adds that Conrad had a good ear.

Which is, as I am witness, true.

Music and picket lines

In 1986, soon after the EDSA revolt, we were working for the revived Manila Times, and picketing it (a long story for another day) – Noel Cabrera, Fort Yerro, Malou Mangahas, Sheila Coronel, Lily Lim, Thelma Sioson.

It was boring, of course, having nothing but our placards while we walked in circles under the sun on a sidewalk in the Scout area.

Sympathizers from Business Day’s union came – Mon Isberto, Daisy Mandap. Journalist friends Nona Ocampo, daughter of activist Satur, and Margie Logarta also came. I recall Gringo Honasan, fresh from EDSA Revolt fame, coming to visit, although he could not resist playing to the gallery of the Times’ security guards and, disappointingly, made light of our heavy picket.

Conrad, who was not in media then but knew I was at the picket line, dropped by. One afternoon, he handed us a song. On the sidewalk, under a big old tree, Conrad had sat down to write the music and lyrics to a vigorous protest song.

Naturally, we sang it with gusto. In my recall, he accompanied us on the guitar. The fellow played good guitar, in case I failed to say. Classical guitar, no less.

Once he accompanied his dear and lovely friend Celina as she sang at the book launch of her father, Adrian Cristobal. And so it was that, at the Manila Polo Club in Forbes Park, in a barong to which he was unaccustomed, before a crowd he would never call his, Conrad played the guitar to “Kundiman ni Abdon.”

A picture of this not-so-common sight landed in the lifestyle pages of newspapers, providing his “impoverished” musikero friends an excuse to rib him big time.

See, of all Conrad’s many attractive features, one stood out for me: He could make himself a normal, regular, ordinary guy.

His was a highly evolved intellect. That he’d spent years devouring books, from Russian ideologies to Greek philosophies to English classics; and having taken electives, while still a sophomore and a junior, with upper classmen to listen and learn, without thought of the Ateneo diploma he never got in the end – all this had made him a really formidable mind.

He could mow down enemies, make mincemeat of naysayers, send villains to the moon. But the best of it was, he never let his huge intellect get in the way of being nice company. I saw how he maneuvered to make favorite friends forget how smart he was. He liked just being one of the boys.

All the banshee, pointless exchange, miscomms, mixed-up messages, and constantly repeating anecdotes that were the stuff of drinking sessions was just the stuff he reveled in.

Which is, I am guessing, why he taught himself to write so fast. The drinking, after all, could begin as early as six in the evening!

That – and his self-effacing talk, ridiculous asides, quick laughter, not to mention that the guy was a great listener – made him the favorite, the star figure to be honest, in a barkada that through the years changed members only slightly and remained small.

Publicly, he did make himself available, even picking up on an offer of a European cruise from the posse of Maria Montelibano and whooping it up in Germany’s Oktoberfest with his partner-in-crime Pancho Lara. But these excursions came few and far between and were always with circles he respected or considered friends or, if lucky, both.

Privately, he did not stray far from his small, tight circle made up largely of musikeros.

And then he stopped writing

Then, quite suddenly, in 2014, Conrad stopped writing.

He disappeared from the Inquirer. Except for a notice in the Op-Ed page saying he was on medical leave, not much was known.

Fact is, he had suffered a massive stroke from which he did not only not recover, it was something from which he would turn progressively worse.

Conrado de Quiros died on November 6, 2023, at the age of 72.

At his wake, as his old old friend, I read my letter to him.

This is a goodbye letter to a friend:

It’s become a bit long because I fancy myself my Friend’s soulmate.

The running joke between us, whenever I espied behavior I wasn’t sure I approved of, was that I could write his autobiography – yes, autobiography – because I knew him so well.

With that threat of immortal ruination hanging over him, he had better behave.

That would coax a chuckle out of him, plus the signature smirk he had that passed for a smile.

And, I do know him well, I wasn’t kidding.

Through the bad years, when his moves were tentative, indecisive, juvenile; and through the good years, when his actions were certain, bold, adult – I was there.

Through the good failures and bad triumphs – I was there.

Through the bad judgments and inspired choices – I was there.

And yet, in the here and now, I am not sure soulmate is a word I can still use for us two, because I have not – I could not – see him in the last nine years.

Nine years can be a lifetime.

Particularly when these are nine years I have come to call, with reason, The Lost Years.

Indeed, they are The Lost Years: 2014, the year of the cruel stroke, to 2023, the year of his cruel death.

Nine years when he was lost to the country, lost to friends, and, I now believe, lost even to himself.

A massive stroke had felled him and much that came after had failed him massively.

Suddenly, this man – whose every thought on everything that assuaged society or that assaulted it, had been printed, broadcast, anthologized to reach the millions hungry to make sense of it all – was nowhere.

No one knew what was going on in his mind.

And really, who knows?

Maybe my Friend, had he been surrounded by people of his choosing and surrounded by them often and regularly, would have remained interested in the world.

Maybe my Friend, always drawn to the bohemian life, had wrongly been deprived of stimulation from the unconventional, the untested, and the unusual, pushing him into an abyss from where he could no longer be reached.

Maybe my Friend, forever the vigilant subversive, understood that his freedoms were slowly being stripped from him until one day he found himself with nothing to fight with or fight for.

Or, maybe my Friend simply needed more music in his life, that most constant of his passions, of which he never got enough in his last nine years, certainly not from those he wanted it from the most.

Or, just maybe, my Friend’s mind could have been unlocked by means still untried.

He certainly had more going for him than French journalist Jean-Dominique Bauby who, following a stroke and coming from weeks of coma, completed The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, with just the use of his eyes, the only part of him that he could move and that he was trained to blink, until blinking unlocked the man inside.

Who knows?

Because I had not – I could not – visit my Friend, I remain as ignorant as his next best friends, the lot of them writers and musicians also deprived of visits, and thus were my Friend’s thoughts weighed under, trapped inside a terribly thinning frame, never to surface again.

And so I console myself with moments from a friendship going back to the early ’70s, when we were both annoyed citizens who just happened to write, until the mid-’80s, when we both became writers who just still happened to be annoyed citizens.

From those moments, of course, I have retrieved other recurring moments.

My Friend is drinking beer – and eating steak at Borromeo’s near the former JUSMAG, in a garden, in the middle of the day.

He is drinking beer – and devouring sisig at Welcome Rotunda in a dive that bursts into life evenings, as the band belts out: “We are the champions, my friend. We’ll keep on fighting till the end…”

He is drinking beer – in Ihaw Balot Plaza, and the boy serving up drinks has stacked empty green case after empty green case on the cement floor at the foot of the table. On a good night, the stacks reach the height of the table or higher, and that’s just four guys consuming everything because I can only take coffee and pineapple juice.

He is drinking beer – in Remembrances in Malate, in Meyrick’s across UST, in Bistro ’70s on Anonas, in Pook Luntian on Timog, in Conspiracy on Visayas Avenue.

If I hadn’t fallen away from the drinking sessions, maybe because I was getting acidic from all that coffee and pineapple juice, I’m sure I would have more dives on my list.

Surely, my Friend was the kind to drink and eat heartily. For the longest time, he was also a big carnivore. His appetites, one might say, were robust.

But what one could totally miss in all this is that he was so because he was basically shy.

He gravitated toward the solitary, or at least the silent, activity, which is probably why he was pretty good at chess.

It was at chess that our barkada Butch Hilario proved to himself that our Friend had a photographic memory. See, at times they played blindfold chess.

Although Butch said that, truth to tell, he kept his eyes open all the time. It was just our Friend who kept his blindfolded. Truth to tell again, Butch admitted he never won a single game. Eyes open or shut, our Friend won all the time.

Yes, my Friend is shy.

So shy that he simply could not shoot the breeze unless he was a little under the influence, and the more breeze he had to shoot, the more influence he had to come under.

Otherwise, he was incapable of small talk. He would just sit alone in the dark, nursing his San Miguel, his face pasted with a smirk that passed for a smile.

But, yet, he was not at all a dreadfully serious guy, not the whole entire day anyway.

When he was out enjoying his music, which was every chance he could get, he just wanted to be left alone to enjoy, please. But he was famous, and it nearly always happened that in a pub, a fan, recognizing him, would invite himself to his table and start debating, usually about politics and politicians.

He hated that.

It disturbed his peace – a peace he always got from beautiful lyrics and musical instruments and voices made in heaven.

Leave him with his hard rock. He was happy. And his jazz, especially his jazz. He could keep guitarist/vocalist John Pizzarelli’s music going on in his car for months! He also connected to protest songs and was friends with lots of activist singers. He more than tolerated pop. And, although he played classical guitar, he could just as easily riff the chords of “When I’m 64” and “One Note Samba.”

Anything music was fair game.

But, more and more during The Lost Years of 2014 to 2023, he turned to ’60s songs, the songs he began with, such as the peaceful rhythms of Crosby Stills and Nash.

Yes, all sorts of superlatives have been heaped on my Friend during the 23 years – 1991 to 2014 – that he bylined “There’s the Rub” in the Philippine Daily Inquirer. Nine years after he stopped writing, the tributes pouring in remain the same.

He is called erudite, cosmopolitan, an intellectual, the greatest hard-hitting columnist bar none, a genius, the spokesperson for a generation, and that most common of adjectives thrown his way: brilliant.

All the noise would be correct, certainly. Yet very few know, for this once robust man with the once robust appetite, there have been many moments away from the bombast.

I recall one in black and white. We are in Economia in Sampaloc, my home. He appears one quiet afternoon, tall, still too thin, single, and quite excited.

He tells me he’s found the girl he would marry. This is a big announcement for him.

He is not good with the ladies. He isn’t smooth.

Born in Manila and raised in Bicol in a poor family, he told friends the story of how, as gleeful young students in the province, he and his male friends would hold hands and race bikes in the streets and think nothing of it.

He grew up in a time and place of abandon and innocence, with the only one to keep him towing adult rules, particularly when it came to grades, was his father, who died too soon.

He had come to Manila in his late teens only because he graduated valedictorian at the Ateneo de Naga, which came with the prize of an Ateneo de Manila University scholarship.

Now here he is in my house announcing a momentous event in his life. We’re soulmates, remember?

He is proud to say that the girl, whom he says has a famous family name, commutes via jeepney, like he does, and is into piano, like he is into guitar.

What’s more, he says, with the half smirk that passes for a smile, she is “pretty.”

My Friend is big on pretty.

And that day, he didn’t know how good fortune could’ve smiled at him so.

We lose touch for many years. I don’t know how his writing is going, he doesn’t know how mine is.

Then comes the moment my cousin Susan, exactly my age, dies at 30. I am looking at my old directory and find my Friend there. The number still works. He comes to the wake in a chapel in a quiet neighborhood of Banawe.

We get a chance to cover our pasts and presents.

Of the past, he brings up my arrest and interrogation in ’74, the second year of Martial Law, when I was 23, and he, 22.

Timidly, and then in a rush, he asks if I had given up his name to my interrogators.

He says he had no one to ask and just needed to know if he had a dossier somewhere, the better to take precautions.

He knew that I knew that just months into Martial Law in September 1972, his mother, brother Paul, and he had rented an apartment that became the underground house for a band of cultural activists.

The family fronted for the UG group – and it was no cushy life. It was, in fact, life and death at every turn.

Any one of them could be shot, or worse, at any time – including his mother with the beautiful patrician features and the beautiful patrician name, Julieta Sotomayor de Quiros – even if she was kept in the dark so that she could carry on under the regime like a regular widow with sons to raise.

But, first things first.

I told my Friend I never gave up his name or his brother’s or his mother’s, nor did anyone among those I was arrested with – Bienvenido Lumbera, Ricky Lee, Flor Caagusan, Bobby Tuazon, Cesar Carlos— through 10 days of incommunicado and interrogation in Aguinaldo and close to one year in prison in Bonifacio, as proof of which their apartment was never raided and he and family never hauled to prison.

That gave him some peace.

Of the present, he says he was working for Adrian Cristobal.

Tentatively, and then in a rush, he explains that Adrian was adopting good writers out of work because of Martial Law, and giving them jobs.

Adrian, of course, was speechwriter and spokesperson for Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

And this is where I catch up to different moments in my Friend’s life.

I see then that my Friend is someone who can live with two worlds clashing inside him, someone who can navigate the contradictions within because he’s told himself to be rational, pragmatic, in the moment. He’s told himself these are the cards he’s been dealt.

On the one hand, he is roped in by his new role as head of the family to write sections of Notes on the New Society, a book officially authored by Marcos Sr. and is required reading in many schools and government offices.

On the other hand, he knows he once chose to go in the very opposite direction – and, verily, should again.

But, lest anyone not know it, the damage wrought by harboring the contradictions between how one believes and how one lives is something my Friend understands more than anyone who might think to reproach him.

My Friend is the kind to punish himself before anyone can even think to pick up the first stone.

He knows the side of right.

But, he is also the kind to become stuck in the bog.

One night, very drunk – I remember it was on one of those Broadway streets with the massive, scary gnarled trees – he suddenly throws open the car door and lets half his body out. I am driving, it’s a brand-new car, and between answering to my father for any ugly dent and my drunken Friend spilling his guts on the pavement on streets known as haunting ground for the White Lady, I really don’t know how I survive the night.

Getting his senses back, he slumps, says: “I could’ve been somebody. I could’ve been a contender.”

It is Marlon Brando’s line from On the Waterfront.

As Brando looks at his life’s choices and twists and turns, he sees that he’s taken himself out of the big fight, out of the big race, out of the big championship, and even farther off, out of the list of contenders.

In those lines, my Friend sees his own life.

It is a strange night even for one who fancies herself a soulmate.

My Friend spoke too soon, of course.

He was 36 or 37 at the time. He was yet to rise to his greatest moments, but he did not— no one did— know it then.

The greatest moments when he, wielding the pen that never failed him, would become the eloquent observer of our crazy life, a rampaging pundit, a thorn on the side of the mighty, an angry citizen tapping into his gifts of lucidity and language to lead the charge of the righteous, several days a week through an unbroken 23 years, in the biggest newspaper in the land.

He would not just be a contender – he would be a champ!

During those years, I catch one important moment vividly.

There was a Sam’s Diner on Quezon Blvd., with its catchy 3D logo that was half the face of a vintage car jutting out of the facade. The barkada liked hanging out there. Open in the late hours, it was brightly lit, and everyone, including the waitresses, who by the way moved around in roller skates, were nice and friendly.

One evening there, we find the place more sober than usual. One of the girls had been assaulted and murdered. A tabloid had carried the news.

My Friend seethed inside.

We were all asking questions of the servers in the diner, and every detail they filled us with made my Friend’s rage settle deeper and harder.

Then his column came out.

It asked the universe what and where and when it was that made sense to take the life of a girl walking late at night because her job demanded it, a girl who was a breadwinner hurrying home to rest the legs that had been on skates all night…

The column stayed with me.

It was a tour de force in writing; it was a tour de force in empathy.

Through the 23 years that he wrote – of what pained ordinary people, of afflictions arising from the greed of the powerful, of the selflessness of overseas workers and tribespeople and church activists, of unforgivable state abuse, of the beautiful and the kind and the generous in our midst – my Friend was rewriting his own life.

He was making up, steadily, ploddingly, and knowingly for the years he had gone in the other direction.

With every moment of writing, he was lifting himself out of the bog.

My Friend had both head and heart in his mighty pen, and so, too, in his crusty typewriter, next in his bulky computer, and finally in his sophisticated laptop. He was a writer with few equals or none – and he knew it.

Once I said, “Look at these plagiarists putting their bylines on your thoughts.”

And he said something he’d use time and again to rile me whenever I felt protective: “Forget it, there’s more where that came from.”

Wow, ang humble, ha. There would go the smirk that was a smile that was also contrition not expressed.

As for his penchant for praising females – from movie stars to party leaders to civil libertarians to models – largely because they were beautiful, I would always shake my head.

I would tell him that almost unbeknownst to him he was quite quick to assign virtue and quite slow to find fault with those who were physically beautiful.

I would add: Wow, hindi ka mababaw, ha. Paano na nga yung autobiography?

And there would go the smirk again that was a smile that was also contrition not expressed.

And, it is true! Over many of life’s moments, my Friend has not always been exemplary.

He can get stuck with his views, listen only to himself, believe he’s got all the answers. He can be downright stubborn. It was irritating.

This is particularly so with matters of health – his own.

My Friend has had problems with his lungs since he was young. On a barkada trip to Pangasinan, we drove over rice grains drying on the highway. Soon, he had difficulty breathing. The car windows were down, and he’d inhaled stuff that assaulted his lungs. No one else in the barkada was in any way affected.

His problems with uric acid came later in life, but this one often did obvious damage.

He used to say he knew more about gout than the doctor he went to who just kept prescribing Colchicine, which he took a lot of anyway, and which, when his son was a toddler, he’d made the boy ingest by mistake, rendering the little one obedient throughout the morning.

Any way, whenever he took one too many salmon appetizers from those silver trays at ritzy events, for sure in the next days his toe or ankle or knee or elbow or finger would flare up, something that became lifelong torture.

But even knock-out pain couldn’t make him hold off with the beer, wine, and tapas for good, and we got used to him opening the door in crutches. Typical of our Friend, he’d make us forget the big wooden things with some putdown of himself: “Some people think lofty things to make a difference. I just think of walking and breathing.”

Then, given his many lifelong medical problems, he began to believe he had the smarts to self-diagnose.

A barkada, musician Rey Abella, began calling him Dr. de Quiros, to which he responded with his signature smirk, even as he continued to believe he had the answers.

Funny thing is, there is a good side to stubbornness.

It makes for courage.

He once said about his children that, if the state ever did them harm, he was capable of killing. This was not figurative talk, and he said it with such quiet intensity, I believed him.

He could, for his children.

He could, if it meant standing his ground for them.

Just as he knew his ideas were hated by parties and personalities he railed against, but did it stop him?

Some YouTubers went to the trouble of creating animation that drew him as a fallen Jedi, because once he’d written something along the lines of “Hacienda Luisita is proof of the failure of EDSA,” following the routing that protesting hacienda workers got from the state, and now here he was calling for “PNoy for President.”

Enemies of PNoy made it appear that the change of heart was in exchange for his older brother Emil being named SSS chief and on account of his daughter Miranda working for the “yellowed” – the YouTubers’ word, not mine – ABS-CBN.

In both cases, his enemies were creating fake news. Did any of that stop my Friend? Did he fritter away his fame in safety and comfort? Did he back off?

No, he did not.

It took fate to do that.

And so, we come to this moment.

The moment when we honor this literary journalist, this unbroken warrior, this fatigued servant, this angry citizen – because he is all that; but more than this, because here is a man who did his damndest best with his gifts, bountiful and luminescent, the likes of which we may not see again in a long time.

Sleep, my Friend.

You’ve earned every moment of rest for every moment you were great I have caught and for every moment that I have yet to catch. – Rappler.com

Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon is editor of the recently launched Serve, a sequel to Not On Our Watch. Martial law really happened. We were there., both books additions to our meager Martial-Law literature. Currently, she is EIC of PEP.ph. This piece was first published on PEP.ph.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.