SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This story is part of Rappler’s series on the 10th anniversary of Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan).

Yolanda was one of the most powerful typhoons in history to make landfall on November 8, 2013. The super typhoon claimed thousands of lives and displaced millions from their homes. Ten years later, Rappler visits some of the affected communities to see what life has been like since the disaster.

TACLOBAN, Philippines – She is the third of six children, born a week after Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) hit Tacloban City. The kid will turn 10 soon. She has written her name on the bare wall of their home, the paint darkened by years of grime.

Ykhana L. Niones, the scribble on the wall reads. Her family and neighbors call her Yolanda. Landa for short.

On the cold cement floor lies a mat on which the whole Niones family sleeps. Beside the mat are plastic cabinet drawers containing their clothes and other valuables. Across the room is a door that opens into a dirty kitchen. There’s not much inside, but their family is thankful for it.

For her 10th birthday, Landa wishes for a television set and a proper bed.

She has only the slightest inkling of where her name comes from, when her parents would tell bits and pieces of the story of her birth. All her neighbors in Greendale Residences are Yolanda survivors.

They all have stories about the typhoon that occurred a decade ago. These stories are buried deep. But when asked, the survivors talk like pipes springing a leak.

Newborns among the dead

Cindy Rose Vergara Lequin’s memory of the past decade is kept intact by the nickname of her third child.

“Palatandaan ko ‘yan [noong] buntis pa ako.” (That was my reminder of the time I was pregnant.)

Ten years ago, Cindy wasn’t sure where she would give birth. She kept transferring places – from her mother’s house in Sagkahan before the storm hit, to her mother-in-law’s place in Diit. Because of the storm’s damage, all travels were done by foot.

She walked among corpses. Days had passed since Yolanda hit land, and dead bodies were banal sightings. She heard news that one of her neighbors found dead was with a child.

“Gusto ko umiyak, pero lakad nang lakad lang ako makauwi lang ako,” said Cindy. “’Pag tingin ko sa kalsada, madaming mga patay na. Wala na akong pakiramdam – parang dere-deretso na lang akong naglakad.”

(I wanted to cry, but I kept on walking just to get home. When I looked at the streets, there were many corpses. I was numb already – I just kept walking.)

Even when she was in labor, she had to walk. No vehicles would stop to give her a ride.

In the late afternoon of November 13, Cindy was waiting to give birth at the Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center. When night came and her baby still wouldn’t come out, the medical personnel on duty told her to wait outside the emergency room.

That night she remembered many patients milling around. Women were giving birth on a pile of mattresses. Expecting that the wait would be long, Cindy walked back to the evacuation center in Sagkahan.

“Parang pabilisan ng panganganak,” Cindy said. (It seemed like mothers were racing to give birth.)

But she had to return sooner than expected. She was back at the hospital by 3:40 am.

At 4 am on November 14, Cindy welcomed her third child to a world on the brink of destruction.

Chapel of memory

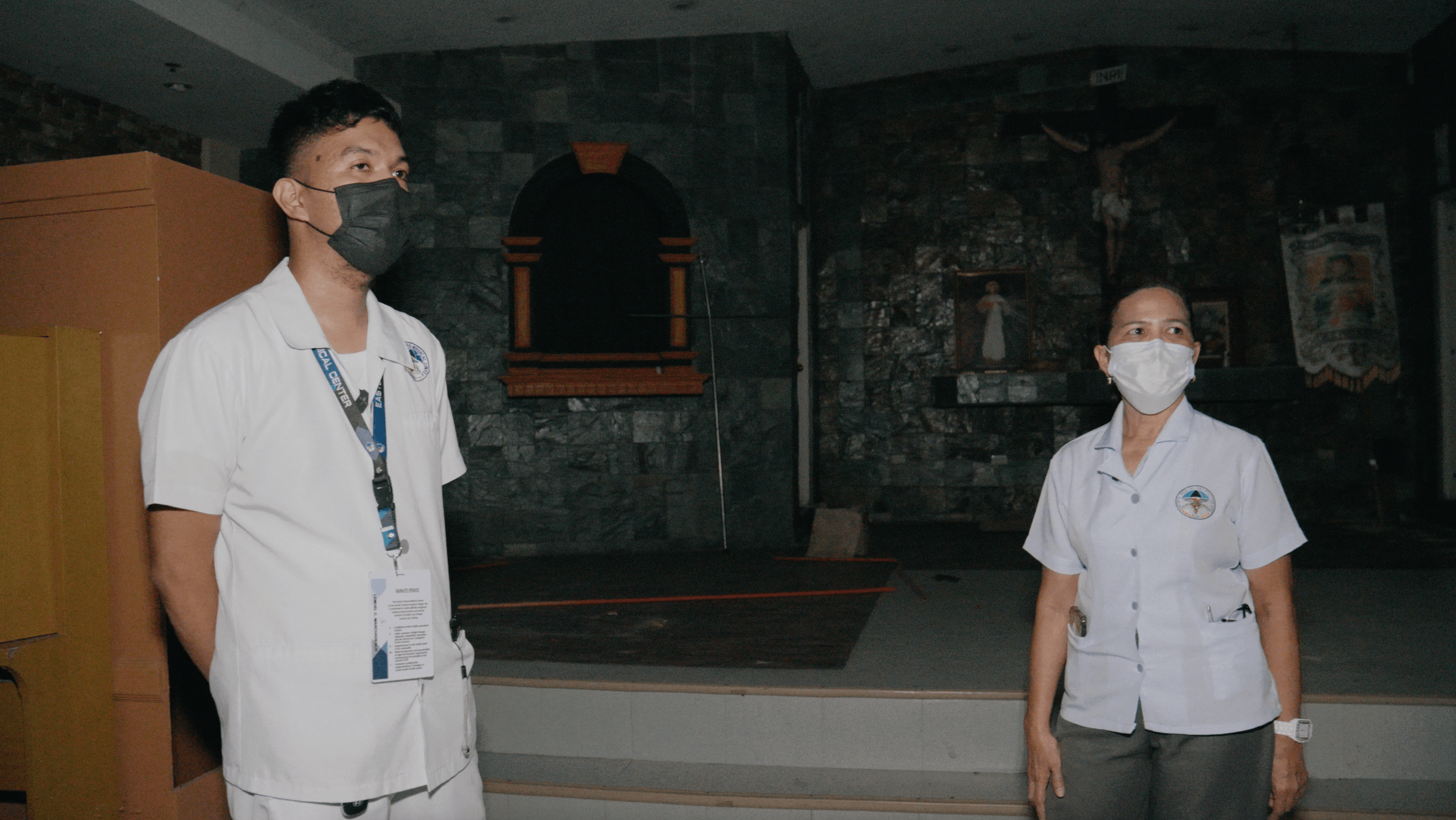

Midwife Brenda Achazo and nurse Lemuel Marchadesch were overwhelmed by memories as they stood inside the empty chapel of the old Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center.

Much has changed. The chapel is abandoned. It is quiet as a crypt. Gone are the cries of newborn infants, the repartee of medical staff, the hushed conversation of new parents – sounds of the chapel when it was Tacloban’s only functioning maternity ward and delivery room during the desperate days of Yolanda.

Not all babies born in this chapel survived, as was recorded by journalists covering the aftermath. But Landa was one of those who did.

She may have been attended to by Brenda or Lemuel. But with a little under 30 babies under their care during those days, they do not remember.

“Entering this chapel now, I remember the situation, and I can hardly believe I was able to deliver babies without equipment,” said Brenda, her eyes scanning the dark, musty room.

Though it’s been a decade, her memories have retained their powerful grip.

She remembers how packed the chapel was, yet how quiet many of the mothers were, deep inside their heads grappling with the death of a loved one, in some cases, the father of their new child.

She remembers the row of cribs in front of the altar, where premature and sickly babies lay. Green oxygen tanks stood over them like strange guardians. Plastic tubes spread out like octopus tentacles connecting a single tank to multiple infants.

The left side of the altar functioned as a makeshift delivery room. For privacy, a blanket was slung across the foot of a pile of foam mats that served as a delivery bed.

Every now and then, Brenda would run to the flooded ground floor, to the original delivery room, to fetch more supplies. She would wade through corridors swimming in mud, placenta, ampoules, and needles.

Above all, she remembers the darkness. They delivered babies with nothing but pen lights or cellphone lights, borrowing from fathers when their batteries ran out.

They prayed infections would not arise from suturing instruments that could only be cleaned with rainwater collected by doctors.

On duty on the day Yolanda hit land, Brenda had no contact with her family for days. With the hospital so near the sea, her children assumed she was dead, even as she was busy ushering in new life.

“Sinumpaan ko ‘yan, na tumulong or to save a life. Call of duty,” said Brenda. (I made a vow, to help or to save a life. Call of duty.)

Nurse Fe Anelia Sia had a different problem. It was not her shift when Yolanda hit, and she could not quickly get to the hospital because of the floods.

She had heard rumors that no one in the hospital survived. Four days after landfall, she walked eight kilometers from her house to the hospital, not knowing what to expect.

When she arrived, her colleagues wept for joy.

“We were all crying because it meant those on duty could finally go home. I brought them hope that they could go home to check if their families were alive or not,” Fe told Rappler.

For two weeks, doctors, nurses, and patients subsisted on rationed water, biscuits, and sardines. Breast milk supply quickly became a problem as the newborns went through the hospital’s stocks and traumatized mothers had a difficult time producing their own milk.

“I admire my colleagues…. We had to suppress all our stress, our fears – fear for the condition of our families, fear for the future of Tacloban,” said Fe.

There were happy moments amid the desperation.

A visitor bringing coffee was a celebrated guest. But the real hero, in Fe’s memory, was the man who brought the nurses fresh underwear. Finally, after endless days and nights, they could feel clean down there. Comic relief came from unexpected circumstances.

Neither Fe nor Brenda could recall recently meeting any of the children born in the chapel. But the thought that the babies then are now 10 years old filled them with gladness.

“They need to treasure their life. God gave you a chance to live. Perhaps they have a mission on this earth they need to fulfill,” said Brenda.

Life after Yolanda

Cindy spent two days in the chapel. Carrying Landa, she returned to the Sagkahan area, where her partner lived in a building with other families.

Years passed, and Landa was followed by three more siblings. They are all girls, except for the youngest.

When they received a housing unit in Greendale in 2016, they were grateful because before that they did not own a house.

But 37-year-old Bernard Niones, Cindy’s partner and Landa’s father, found that after a decade, not much has changed. He lamented the life he has given Landa and her siblings.

“Ngayong November 14, mag-te-ten na siya, wala siyang nakikita sa bahay ko kahit anong gamit man lang,” Bernard said.

(This November 14, she will turn 10 soon, but she still hasn’t seen any improvements in the house.)

It has been a hard life. Every day, Cindy and Bernard would wake up at 2 am to buy the day’s catch from the market. They would sleep a bit after, only to wake up again at around 5 am to cook breakfast and fetch bath water. Cindy sells the fish first, then Bernard takes over so she could check on their children as they get ready for school. Bernard said he sometimes dabbles in construction work to augment their income.

Even though they own a house now, they are not convinced that life has improved drastically a decade after Yolanda. Water issues beset the housing projects they live in. And because they weren’t able to pay their bill last December, the family has been living without a steady water supply for almost a year now.

Other neighbors have been spreading stories about the sorry state of their house and their many children, said Bernard. But all these go in one ear and out the other.

“‘Yung naisip ko lang, makapaghanap lang ng pera para makapagbaon sa kanila, ‘di lang mapabayaan ‘yung pag-aaral nila,” he said.

(All I think about is earning money to give my children allowance so they won’t neglect their studies.)

Tacloban’s children

Landa was home on the day we visited her family because it was World Teacher’s Day. On what would normally be a school day, Tacloban City’s children were out in the parks.

In a park beside the Astrodome – a site of tragedy during Yolanda – high school students practiced dance routines on the grass. In ordered rows, they twisted and swayed, turned, and jumped, laughter punctuating mistakes and teasing.

On a quiet corner stood a memorial to Taclobanons who died in the Astrodome. Victims’ names were painted in white, upon dark gray plaques facing the sky. Four of the dead were named Yolanda.

It started to rain. Drops of water began to pelt the names of the perished, the rebuilt Astrodome, the sidewalks.

Paying no heed, Tacloban’s children kept on dancing. – Rappler.com

ALSO ON RAPPLER

- After Yolanda: A causeway threatens efforts by locals to restore a mangrove forest

- PANOORIN: Mga Kuwentong Yolanda

- Rappler Talk: Alfred Romualdez on learnings from Yolanda, 10 years later

- After Yolanda: A teacher’s dream for the children of Guiuan

- 10 years on, Yolanda survivors grapple with memory, delayed recovery

- Rappler Talk: Guiuan’s decade of recovery after Yolanda

- WATCH: How the people of Eastern Samar take care of the environment

- Rappler Recap: ‘Work is not done,’ Marcos says of Yolanda recovery

- Rappler Recap: Tacloban residents light candles for 10th year of Yolanda

- On Yolanda’s 10th year, groups urge gov’t to ‘hold big polluters accountable’

- Marcos resurrects issue of ‘uncounted, unrecorded’ victims of Yolanda

- A decade later: 15% of Yolanda houses unfinished, thousands unoccupied

- [Under 3 Minutes] Kumusta na ang Yolanda housing projects?

- Part 2: Water, electricity issues bog Yolanda relocation plans

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.