SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

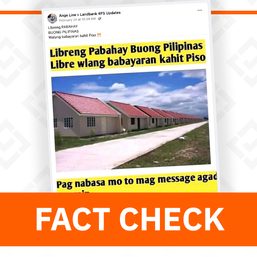

This story is part of Rappler’s series on the 10th anniversary of Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan).

Yolanda was one of the most powerful typhoons in history to make landfall on November 8, 2013. The super typhoon claimed thousands of lives and displaced millions from their homes. Ten years later, Rappler visits some of the affected communities to see what life has been like since the disaster.

Part 1: A decade later, 15% of Yolanda houses unfinished, thousands unoccupied

TACLOBAN, Philippines – In northern Tacloban City, beneficiaries of Yolanda housing site Greendale Residences gather in their multipurpose hall to learn about the art of haircutting.

Edmund Odinada, wearing an apron, takes out a heavy rusty pair of scissors and snips away behind the head of a little boy seated on a stool. Locks of black hair drift to the floor like leaves.

A few of Edmund’s neighbors have joined him in listening to the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority staff who was invited to the housing site to give the workshop.

Unlike some other Yolanda housing sites, many houses in Greendale Residences are occupied. Some of the longtime occupants have become community leaders and regularly arrange livelihood workshops for their neighbors.

A baking workshop is slated in the coming days. Edmund mentioned a regular youth dance competition. He pointed to blue-painted curbs in front of every house: “We were the ones who painted that.”

But just as apparent as the liveliness of the community is the community’s main hardship.

In almost every corner, rows and rows of large blue plastic canisters are seen. They are waiting to be filled with water from one of the community pumping stations – large metal faucets from the ground that produce water when an attached lever is energetically pumped.

Even very young children work the pump on orders of an elder who notices they are running out at home. Men and women heave blue jugs full of water on their shoulders. Though all Greendale houses have pipes ready for water, only a few are connected to a water source.

In one of the pumping stations, pumping water has been so ingrained in community life that a schedule has been hung on the wall.

Beside the sign, a young man named Mauricio wordlessly pumps the lever before a colony of neatly lined up blue canisters. Using only his fingers, he told us he is paid P30 ($0.53) to fill up around 20 to 30 canisters. He does this six times a day.

Later on, we spotted a water truck parked by a tank beside a school built for the housing site. The driver told us he supplies water to many Yolanda housing sites on orders of the Tacloban city hall.

“Kulang pa nga ‘yang tubig na dala namin (Even the water we bring is not enough),” he said.

“It gets so hot at night that you need to fill up two or three jugs with water, but soon, it runs out. The water dries up fast. Then you have to wait another hour or two hours to pump more water,” said Troy, a regular visitor in Greendale.

Rounding a corner after the multipurpose hall where people are learning to cut hair, we arrived at the home of Cindy Rose Vergara Lequin, a fish vendor and mother of six.

It is a single space, a corner of which is occupied by a walled bathroom. It is devoid of furniture, save for two small tables and an electric fan. A foldable mat suffices as a bed for their children. She and her partner sleep outside, in the same space as their makeshift kitchen.

During our interview, a cracking sound from above frequently interrupted the conversation. It was the sound of the metal roof bending under the afternoon sun.

Cindy was effusive in expressing her gratitude for the free house. When Yolanda washed away her seaside village, she and her partner had no home of their own and had just been living with their parents.

But she said life in Greendale is hard, especially during times of heat and drought. Water drips from the roof when it rains hard.

The government housing units are meant to be starter homes. They are given for free but beneficiaries are expected to foot the bill for improvements – for paint, added fixtures, and the like.

But Cindy and her partner can't afford these improvements with the income they get. Both of them are fish vendors and they used to sell in Tacloban City, where foot traffic is constant.

But since moving to Greendale, 20 minutes by bus from the city center, they have not been making as much. On top of that, the one-way bus fare would set them back by P30 ($0.53), which is a lot if you earn only P500 ($8.78) a day and have a large family to support.

'How will I live there?'

The buses are a fairly recent development, a response to complaints from Greendale residents about a lack of transportation to the city.

But even that has not convinced fisherman Rodolfo Delleva to live in the house reserved for him in another housing site near Greendale Residences, Guadalupe Heights.

"How will I live there? There's no livelihood there. My livelihood is here, by the sea. Somehow, I'm able to earn enough to buy rice. So until now, we still live here," he said in Filipino.

Tacloban City Mayor Alfred Romualdez, in an interview with Rappler, had downplayed an observation that relocation near the coast still happens because fishermen want to be near the sea for their livelihood.

Romualdez had said the seas around Tacloban don't have much fish left to make a living out of.

To this, Rodolfo snorted.

"Kasi, maraming ano dito eh, alimasag, isda – sari-saring isda nandiyan. 'Yung mga shell, tulad ng halaal at tahong, marami pang iba. Dito, araw-araw nangingisda diyan. 'Di ’nyo masasabi na walang isda. Dito lahat ng tao, dito pinagkukunan ng pagkain pang-ulam."

(There are many crabs and fish here – different kinds of fish. There are shells, molluscs. Every day, people fish here. You can't say there is no fish. All the people here get their food here.)

Rodolfo lost everything to Yolanda's storm surge. His house was in San Jose district, the worst-hit district in Tacloban City, where at least a thousand died from the storm surge alone.

Despite this trauma, he decided to rebuild his house on the same spot, using debris washed into his vicinity by Yolanda. The typhoon takes, the typhoon gives.

In Anibong district, where the iconic half of a stranded ship has become a mini-museum and Yolanda memorial, Matt is getting ready to leave.

The inside of his pink house is exposed to the elements, like a morbid dollhouse. This was the work not of the storm surge, but of city hall, which had demolished houses in the seaside area to enforce its "no dwelling zone" rule.

Matt is preparing to move his young family to Guadalupe Heights, the same housing site Rodolfo had refused. He is doing this because he has no choice, he said. He is just waiting to receive some pieces of wood that he can use to make a door. But what he is most anxious about is the lack of electricity.

Reasons for delay

Mayor Romualdez himself admits that many of the housing sites in his city are deficient. It got complicated when we asked him why and who is to blame.

He said that in the years immediately following Yolanda, there was a lot of pressure from the national government to speed up the housing projects, which in turn, led the NHA to pressure local governments like Tacloban City to quickly issue permits for the projects to commence.

Romualdez said city hall had no say in how the houses were designed but the local government was pressured to accept them anyway or risk being labeled a hindrance. Turns out, he said, many of the contractors for the housing projects were problematic.

"Unfortunately, many of them (contractors) did not comply. That's why we have problems there of substandard houses that were built…. The recourse that they (NHA) were taking was to file cases against these contractors. And this is what I said, 'You know, that case is going to take forever,’” the mayor told Rappler.

In summary, these are the reasons behind the problems in Yolanda housing, according to Romualdez:

- Lack of water connection inside houses because of "holes" in pipes laid by NHA contractors. City hall will have to repipe some houses.

- Need to rehabilitate old pipes to connect housing sites to the main Tacloban water system.

- Lack of titles for housing beneficiaries, which discourages them from spending on improvements on their houses.

- Failure of some contractors to finish the projects, necessitating termination of contracts and a restart of the entire bidding process.

Minimum standards for housing

But the NHA denied its housing units are subpar, though it admitted they are far from aesthetically pleasing.

In an interview with Rappler, Constancio Antiniero, NHA regional manager for Eastern Visayas, said all housing projects met the minimum requirements of Batas Pambansa Bilang 220, the law on socialized housing. The law lays out basic standards, like how detached housing units must be at least 72 square meters and row houses must be at least 36 square meters. It states required dimensions for doors, windows, and ceilings.

It requires houses to provide complete living facilities for one family – living, sleeping, laundry, cooking, eating, bathing, and toilet facilities.

But the same law requires water supply for individual housing units, with water meters for all. The situation in many Greendale houses is a violation of the law.

“Water supply shall be adequate in amount and reasonably free from chemical and physical impurities; a main service connection and a piping system with communal faucets to serve the common areas like the garden, driveways, etc. shall be provided. Pipes branching out from the main water line shall service the individual units which shall be provided with individual water meters,” reads Batas Pambansa Bilang 220.

The law is 41 years old and was signed by former first lady Imelda Marcos, who, at the time, was minister of human settlements.

"To tell you frankly, our housing units are really not presentable because these are just core starter housing units," said Antinierro.

"What can you expect from a P290,000 ($5,091.81) house-and-lot package if we put bedrooms, tiles? They are really core starter housing units because the NHA believes that it is now the responsibility of the beneficiaries to improve the housing units," he also said.

But what about housing projects like Carigara Housing Project 1 that are unlivable by any standard? Antinierro said it is among the 60 Yolanda housing projects that have been delayed for so long that the NHA is in the process of terminating contracts with developers.

Hi-Tri Development Corporation, the failed contractor of the Carigara housing site, was given 60% of the P197-million contract cost. Due to delays, they were made to pay for damages, around 10% of the contract. Despite this, Hi-Tri is still trying to keep the project by partnering with another developer, Chucon Builders Corporation, a company based in Tacloban City. It is a contractor of the Department of Public Works and Highways, mostly for road projects in Leyte like the Tacloban-Palo Diversion Road.

Is the NHA inclined to accept this deal with Hi-Tri?

"It depends on how they are going to respond if we are going to issue the order of termination," said Antiniero.

Termination takes a lot of paperwork and time, which has further pushed back the timeline for housing projects. It is only when a contract is terminated that the bidding process for a new developer to take over the project can begin.

Water problem

What about the lack of water connection that has discouraged beneficiaries from occupying their houses or made life difficult for those who have moved in?

Antiniero again pointed to local governments. In those early years of the rehabilitation work, great pressure on local authorities to speed up their permit process led to their issuance of water source certification documents. This document is supposed to attest to the presence of a water source near the intended housing site.

But according to Antiniero, there were cases when certifications were issued even if there was no actual water source near the site. In other cases, there had been a water source before but it had dried up, either due to extended periods of drought or other reasons.

Meanwhile, it's the local governments that have tried to fill in gaps for the housing projects they have accepted and awarded to beneficiaries. The most pressing problem for Tacloban housing is water.

"To tell you frankly, my target was last year. I keep pushing this. In fact, that's why we have water tankers just to deliver water to them," said Romualdez.

According to COA reports, interviews with local government officials, as well as current and former housing officials, the following are common reasons for delays in Yolanda housing projects:

- bad weather

- COVID-19 pandemic

- suspension orders

- processes for terminating contracts, surveys, individual titling, converting land classifications

- installation of power lines

- descaling due to unbuildable areas

- land claimants preventing developers from starting construction

- requests for design changes from local governments

- rectifications in design specifications

Yolanda-hit communities have weathered all kinds of political winds under three different presidents, yet many of the old problems remain.

The aftermath of a calamity that struck during an Aquino presidency is now in the hands of a Marcos.

Romualdez himself is a second cousin of the President, who won overwhelmingly in Tacloban City because it is the hometown of his mother Imelda.

Is that blood connection bearing fruit for the thousands of Taclobanons who suffered from Yolanda and now still suffer, this time from the snail's pace of government action?

Romualdez said he has "conveyed" to Marcos their need to distribute more titles to housing beneficiaries. The President, he said, has ordered NHA to "fast-track" the process.

The Marcos-time NHA has promised to finish all Yolanda housing projects, including those delayed due to termination of developers' contracts, by 2024.

"We don't allow the Yolanda [projects] to be carried over to 2025," said Antiniero.

"Mahiya naman tayo kasi ilang administrasyon na ang dumaan, hindi pa rin tapos (It would be embarrassing because multiple administrations have passed, and it's not yet complete)." – Rappler.com

$1 = P56.96

ALSO ON RAPPLER

- After Yolanda: A causeway threatens efforts by locals to restore a mangrove forest

- PANOORIN: Mga Kuwentong Yolanda

- Rappler Talk: Alfred Romualdez on learnings from Yolanda, 10 years later

- Call her Landa

- After Yolanda: A teacher’s dream for the children of Guiuan

- Rappler Talk: Guiuan’s decade of recovery after Yolanda

- WATCH: How the people of Eastern Samar take care of the environment

- Rappler Recap: ‘Work is not done,’ Marcos says of Yolanda recovery

- Rappler Recap: Tacloban residents light candles for 10th year of Yolanda

- On Yolanda’s 10th year, groups urge gov’t to ‘hold big polluters accountable’

- Marcos resurrects issue of ‘uncounted, unrecorded’ victims of Yolanda

- [Under 3 Minutes] Kumusta na ang Yolanda housing projects?

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] In the Public Square with John Nery: Abolish the National Housing Authority?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/In-the-Public-Square-LS.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=377px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Under 3 Minutes] Kumusta na ang Yolanda housing projects?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/11/title-card-ls-3.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.