SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 2 parts

Part 2: In Ilocos Norte, a ‘tiny minority’ speaks up vs Marcos Jr.

ILOCOS NORTE, Philippines – In front of the Immaculate Conception Church in Batac, Ilocos Norte, the birthplace of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, tricycle drivers greeted us with a chant: “BBM! BBM!”

BBM stands for Bongbong Marcos, namesake and son of the late dictator who is now the leading presidential aspirant in the 2022 Philippine elections. To many Ilocanos, putting another Marcos in Malacañang is akin to reclaiming lost glory and reliving those two decades of Marcos’ rule – when being from Ilocos Norte was a ticket to work, wealth, and power, and an insurance for paved roads and resilient bridges.

We visited the province in December, in time for Marcos Jr.’s much-awaited caravan here with running mate Sara Duterte but which was postponed due to Typhoon Odette.

In Laoag City, the seat of power of the Marcos-controlled province, only good things are openly said about Marcos Jr. Criticism and attacks are made in whispers, if at all, as residents who oppose the Marcoses shut their doors and windows when it’s time for dinner stories, cautious that their loyalist neighbors would hear them and cause trouble.

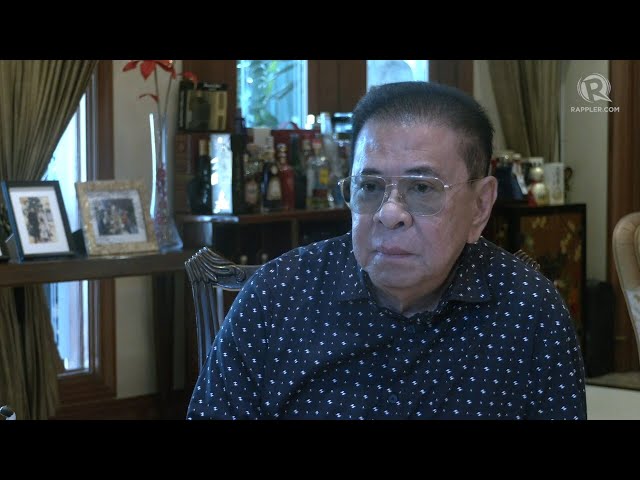

But Manuel Aurelio, the dean of Northwestern University’s College of Law in Laoag where Marcos Jr.’s wife Louise “Liza” Araneta Marcos used to teach, is not one to mince words about the former governor.

“He was a perennial absentee,” said the 81-year-old Aurelio, a retired prosecutor of Laoag and a former councilor of nearby San Nicolas town who has written a book on the province’s history.

Marcos Jr. had served as vice governor and then governor of Ilocos Norte under his father’s dictatorship, from 1980 until February 1986, when they were ousted and exiled in Hawaii.

The young Marcos returned from exile in October 1991, and a year later he ran and won as representative of Ilocos Norte’s Second District. After only one term in the House, Marcos set his sights on the Senate, but he lost his first senatorial bid in 1995, landing on the 16th place in the race for 12 seats.

It seemed too much too soon; even his father before him had served as congressman for three terms before shooting for the Senate in 1959 – and topping that race.

Thus, in the following elections, 1998, the 40-year-old Marcos Jr. decided he was not ripe for another national run. He ran for governor instead, won, and got elected for two more terms until 2007.

Aurelio said it was Marcos Jr.’s provincial administrator, Ireneo Martinez, who was visible during those years. “When I went to the office, Mr. Martinez was there and Bongbong was not there. But of course he came here every now and then, but me, I wished Bongbong was there most of the time, not most of the time away from Ilocos Norte,” Aurelio told Rappler.

Even during his first stint as governor in the 1980s, when his father was president, Marcos Jr. would also only “fly in and out of Laoag,” and it was his vice governor, Roque Ablan Jr., whom residents and public officials would mostly see, a local politician told Rappler.

Marcos Jr. was, after all, in his 20s at the time – he partied, drove flashy cars, and had the time of his life as the only son of the country’s most powerful man.

Marcos the student-governor

It was in January 1980, when Marcos Jr. was barely 23, when he first got elected as vice governor of Ilocos Norte in the first local elections held in the Philippines after his father’s declaration of Martial Law in 1972. Marcos’ party, the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL), naturally swept the races.

While vice governor, the young Marcos went to school in the United States, at Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, where he did coursework from September 12, 1979, to December 20, 1980, and then again from September 1, 1981, to December 20, 1981. He did not earn any degree there, Wharton told Rappler.

Then, in 1983, Marcos Jr., already 26 years old then, was sworn in as governor to replace his aunt, the dictator’s sister Elizabeth Marcos Keon, who was governor from 1971. She had become ill and resigned. Elizabeth is the mother of now-reelectionist Laoag City Mayor Michael Keon, who has been estranged from the Marcos clan.

As governor, Marcos shied away from the media and the public eye. Residents recalled that it was his media-savvy spokesperson Lito Gorospe, a broadcaster, who would be seen on the frontlines. The late Gorospe, not Marcos Jr., would often speak for the capitol. This aversion to media continues to this day. (Nowadays, it’s lawyer Vic Rodriguez attending press conferences and issuing statements on national policies for his candidate.)

In an interview with radio DZME on November 22, 2021, former Ilocos Norte governor and First District congressman Rodolfo “Rudy” Fariñas claimed that in 1998 Marcos had asked him to give way and support his gubernatorial bid. “I supported him,” said Fariñas, who ran for Congress that year.

“Noong gobernador si Bongbong, wala naman po siyang naibigay. Hindi naman po natin puwedeng ipagkaila na ang tatay nila maraming nagawa, pero ‘yung mga anak eh walang nagawa,” Rudy Fariñas said in the same interview.

(When Bongbong was governor, he did not give anything to the province. We can’t deny that their father had done a lot, but the children have done nothing.)

Nonetheless, the Marcoses showed their staying power in the province.

In the last 50 years, in fact, the only non-Marcos to hold the position of governor was Fariñas himself, who occupied the capitol from 1988 to 1998. He is now running for the same post against a third-generation Marcos, reelectionist Governor Matthew Marcos Manotoc, son of Senator Imee Marcos. (After Marcos’ ouster in 1986, several people were appointed as officers-in-charge of the province, including Roque Ablan Jr and Castor Raval.)

Achievement? ‘Tingnan ang nagawa ng tatay niya’

Marcos’ supporters back the campaign slogan Babangon Muli or Rise Again, an allusion to the dictatorship that loyalists claim was the golden era of the Philippines. They hold on to this belief despite historians, economists, and even bureaucrats having repeatedly debunked the claim, showing proof of poverty and debt during Martial Law.

Luis “Chavit” Singson, the former governor who remains the political kingpin of Ilocos Sur even if he has settled as mayor of Narvacan, sat down with Rappler one morning in December 2021 in his home in Quezon City. We asked him what his pitch would be for non-Ilocano voters to choose Marcos Jr.

“Tingnan ang nagawa ng tatay niya,” Singson said. (Look at what his father has done.)

But what has Marcos Jr. done on his own?

“He’s gaining experience. To be a leader, you should be well-educated, well-experienced,” Singson said. “Nasubukan na n’ya lahat, marami nang eleksiyon siyang nasubukan. Siguro bumalik ‘yung…parang dumating na ‘yung [panahong] sawa na ang tao sa pambubugbog sa tatay niya,” said Singson, echoing the defense of Marcos supporters that the sins of the late dictator are not the sins of the son.

(He has tried everything, he has gone through many elections. Perhaps the time has come when people have gotten sick of the criticisms against his father.)

Besides, Singson said with conviction, “It’s his time.”

‘Good in ceremonies’

As for Aurelio, who has seen Marcos Jr.’s terms in various capacities: “I am at a loss for what big projects Bongbong did. I do not seem to know of any.”

Ilocos Norte is a budding tourism hub of not just Northern Luzon, but the entire Philippines.

Could that be credited to Marcos?

Tina Tan, who worked as tourism officer for three months under governor Imee Marcos, told Rappler that “community initiatives were not welcome during Bongbong’s term as governor.”

Tan is the founder of LEAD, which is credited for introducing sandboarding to boost provincial tourism.

“Maybe he doesn’t even know there were such initiatives because he wasn’t visible anyway,” said Tan.

She said it was LEAD which developed and promoted the Laoag sand dunes, but was sidelined after Imee asked for help to develop and promote the Paoay sand dunes instead. “If the Marcoses are not directly involved in a project, you don’t get their support, or if they want your project, they steal the credit for your idea,” said Tan.

Rappler made repeated attempts to interview Ryan Remigio of Team Marcos for this story. Remigio, a local politician and staunch ally of the Marcoses in Ilocos Norte, initially said he would find a schedule, but eventually stopped responding to our messages. Rappler also reached out to Marcos’ spokesperson Vic Rodriguez for a comment, but has yet to get a response.

Aurelio said that, from the matriarch Imelda to her children Bongbong to Imee, the Marcoses were “very good in rituals, ceremonies.” (Imelda, despite having served as representative of her home province of Leyte, was elected as Ilocos Norte Second District congresswoman for three terms starting in 2010.)

“I’m not saying they did nothing that we can remember them by, but they could have done better during their time. Imelda, for instance loved, frivolities,” said Aurelio.

Bangui windmills not Bongbong’s project

Imelda as a first lady loved larger-than-life projects to display her penchant for all things bright and beautiful, like the Cultural Center of the Philippines. The CCP remains today an icon of Imelda’s so-called “edifice complex,” a term coined in the 1970s to describe her habit of overspending on infrastructure to project political power.

Like his mother, Marcos Jr. also wants clear association with infrastructure. All of his campaign ads feature the Bangui Windmills, the towering white mills that peek through the sky off the picturesque coastline of the northernmost parts of Ilocos Norte.

The Bangui windmills are an hour’s drive from Laoag, and were built in 2005 while Marcos Jr. was governor. But it wasn’t his idea or his project.

Records from the Philippine Senate and the US-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory showed that the Philippines had shown potential for wind energy, and that by 2004 this had become part of the Department of Energy’s nine-year energy plan.

Marcos Jr himself said in a 2010 interview with ANC when he was running for senator: “One thing that people seem to think is that it’s a government project. It’s not. It’s a private commercial enterprise.”

The Marcos connection, besides the fact that Bangui was the chosen site during his time as governor, was a lawyer named Ferdinand Dumlao. In 2000, Dumlao, a close ally of Marcos, met Danish Neils Jacobsen at a conference. The meeting led to a site visit, according to the 2010 doctoral thesis on ecological social justice written by noted maritime lawyer Jay Batongbacal.

It’s not clear how it all came to be, but Dumlao, who was Marcos’ provincial special projects director at least in 2004, a year before the Bangui windmills were installed, was chairman of the board of directors of a company called Northwind Development Corporation, of which the Danish Jacobsen was president.

Northwind received funding from the World Bank and the government of Denmark to build the Bangui windmills.

According to Batongbacal’s thesis, citing an interview with Jacobsen, a condition for the Danish funding agreement was to insulate the windmills from politics. “This was the reason why they did not have any high-ranking politicians prominently associated with the project; indeed, in all news media reports, even the governor has been relatively very low-key in regard to the project despite its being an obvious achievement for the province,” wrote Batongbacal, citing Jacobsen.

Today, Dumlao is one of the people behind the reorganization of KBL, party executive vice president Mong Ocampo told Rappler. KBL is the party founded by the late dictator and the vehicle for Marcos Jr.’s first electoral win in 1980, as well as his failed senatorial bid in 1995. KBL revived itself to campaign for Marcos’ 2022 candidacy although Marcos Jr.’s nomination is under the barely three-year-old Partido Federal ng Filipinas.

Agriculture sector felt neglected

Aside from the promise of clean energy and undisrupted power for the whole of Ilocos Norte, the Bangui windmills had become a main tourist attraction too.

Nine years after Bangui windmills, another set of windmills was built in nearby Pagudpud, a town known for its beaches, in 2014 under the term of Imee Marcos. Concerns over safety because of the Pagudpud transmission lines caused protests and even reached the court, ABS-CBN News reported.

The issue for the Pagudpud tribes was that there was delay in paying them royalty for their ancestral domain, chieftain Benny Aguinaldo told Rappler. “The windmills would have been good, but it’s not favorable to us because our electricity rates went up. We cannot afford it,” Aguinaldo said in Ilocano.

Marcos Jr. has been saying that boosting agriculture would be a priority if he becomes president, but Normerto Palaganas, a tribal elder and a farmer in Pagudpud, told Rappler in Ilocano: “Even back then, we have not felt that the Marcoses have helped our sector.”

Least poor, but…

Contrary to what Marcos’ critics have been spreading on social media, Ilocos Norte is among the least poor provinces, according to the poverty incidence data of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) that is measured every three years.

Ilocos Norte belonged to the least poor clusters in the 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2015 reports. These years cover the last two terms of Marcos Jr. and the first two terms of Imee. Ilocos Norte also has one of the lowest poverty incidence in the most recent PSA 2018 to 2021 report, which covers Imee’s last term and the first two years of her governor-son.

White elephant projects

Another indicator would be the audited financial report of local governments done by the Commission on Audit (COA). The 2020 AFR, the most recent, shows that while Ilocos Norte does not have the biggest liabilities, it’s not in the list either of provinces with the highest assets or provinces with the highest revenues.

To many people, a progress indicator is one they can see or touch, and the Marcoses know this. Before Marcos Jr. ended his term as governor, Ilocos Norte took out a loan to build the Dap-Ayan Center, a vacant lot of about 2,000 square meters that he had wanted to convert into a tourism hub. But “this was not sustained in the long run due to lack of manpower assigned by each local government unit and provision of security personnel to guard the area,” Ilocos Times reported in 2015, when the structure underwent a second facelift.

Photographed by Rappler recently, the Dap-Ayan Center is still just all steel bars and cement – far from functioning.

In 2018, just before she ran for the Senate in the 2019 midterm elections, then-outgoing governor Imee Marcos had the province borrow P2 billion from the Development Bank of the Philippines to finance yet again the reconstruction of Dap-Ayan, the redevelopment of the Ferdinand E. Marcos stadium, and the construction of a multi-purpose building behind the capitol, or the so-called “Big 3,” according to the 2020 audit report of Ilocos Norte.

They were supposed to be finished by April 2022, said the audit report, but of the three, only the stadium will meet the target as it’s set to reopen in June.

Ilocos Norte Governor Matthew Manotoc has inherited these projects, even though one of them was started by his uncle when he was just a teenager.

Residents would point to the Dap-Ayan Center as one example of Marcos Jr.’s white elephants.

In his November 2021 interview, Fariñas pointed to another white elephant. He said that Marcos Jr. also took out a loan toward the tail end of his term in 2007 for the construction of the sprawling Plaza del Norte Hotel and Convention Center in Paoay. Fariñas described it as “walang pakinabang at walang kinita ang gobyerno (of no use, and did not result in profit for the government.)”

Indeed, Marcos has the most extensive government experience among the presidential aspirants – 21 years out of total 27 were in the service of Ilocos Norte as their governor and congressman.

Yet, his concrete achievements are debated even in his own province. To his base, however, does this even matter? These days, if survey numbers will be sustained, the once-partying presidential son and once-absentee, once-carefree governor is a breath away from Malacañang. – with reports from John Michael Mugas/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] Improbable vote](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/03/Newspoint-improbable-vote-March-24-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=339px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] 19 million reasons](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/12/Newspoint-19-million-reasons-December-31-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=181px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[New School] Tama na kayo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-tama-na-kayo-feb-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=290px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.