SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

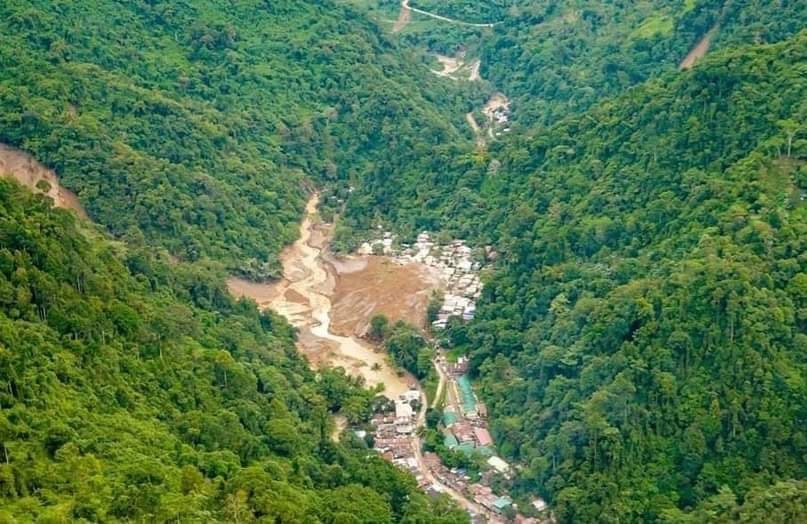

The February 6 landslide in Davao de Oro harks back to a similar disaster in 2008, when residents of Barangay Masara, Maco struggled with a deadly landslide due to heavy rainfall.

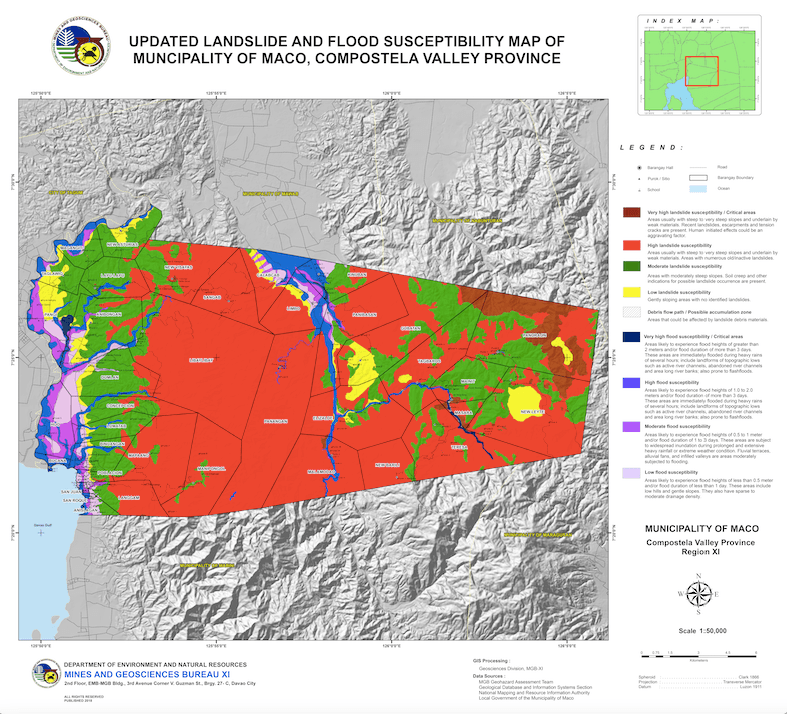

Sixteen years ago, the regional office of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) already declared the village a no-build zone. Successive geohazard mapping and assessment by the regional office of the environment department and the MGB “consistently show[ed]” that the area was “highly susceptible to landslides.”

The MGB said in a recent statement that they recommended back then the immediate relocation of Barangay Masara.

History repeats itself – first, as tragedy, the second time, as a result of negligence. If geohazard mapping was done more than a decade ago, and the area was already found to be highly susceptible to landslides, why didn’t the lessons stick?

The landslide that occurred in Barangay Masara last February 6 killed residents and miners on a bus going to a gold mine. As of Sunday, February 18, the death toll had climbed to 93, according to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), with 35 injured. The number of missing people was down to eight.

Lessons not learned

Back in 2008, Senator Pia Cayetano said that the tragedy could have been avoided or mitigated if safety precautions had been undertaken. “What’s the use of geohazard mapping if it can’t be implemented?” she said back then.

Hazard mapping is one of the ways to minimize landslide risks. It should help local government units determine areas under their jurisdiction where it’s not safe for people to live or work. (READ: Gov’t should use scientific data in hazard maps – Lagmay)

However, despite having completed geohazard mapping and assessment, the MGB can only make recommendations. It’s the local government’s responsibility to implement no-build zones or relocate communities at risk.

Local governments have always had a hard time enforcing the no-build zones in high-risk areas, Teresito Bacolcol, director of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) told Rappler in a message.

Phivolcs deals with volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, as well as communities affected by natural disasters like landslides. (READ: How Phivolcs’ Dynaslope helps avert disasters in landslide-prone areas)

“These individuals are reluctant to leave high-risk zones due to their livelihood,” said Bacolcol.

The Phivolcs director referred to past experiences recommending no entry and no permanent habitation inside permanent danger zones (PDZs). Despite this, government still has to evacuate residents in PDZs, such as when volcanoes are close to erupting or when strong typhoons are coming.

But Bacolcol said they’re not blaming residents. “Essentially, to ensure that people do not return inside the PDZs, local government units should guarantee a source of livelihood, which is not easy in some areas,” he said.

Establishing an early warning system in the community can also help address this, said Bacolcol. “If people refuse to relocate, they should be informed and made to understand the risks of staying in high-risk zones,” he said.

However, while this huge responsibility falls squarely on the shoulders of local governments, they are also looking to the national government for support. According to various reports, Davao de Oro Governor Dorothy Gonzaga said they’re still waiting for the MGB to recommend suitable relocation sites for affected residents.

Meanwhile, Environment Secretary Toni Yulo-Loyzaga only repeated the obvious but seldom-applied principle: the need to integrate hazard maps in decision-making. “A hazard does not have to become a disaster,” she said.

But ensuring people’s security during disasters doesn’t stop after mapping hazards. People are naturally wired to think about the jobs that feed them, the houses that keep them safe.

According to Science Secretary Renato Solidum, there’s a discrepancy between risk appreciation and livelihood opportunity. Why leave a place when there are no guarantees of making a living?

In the same way that safer relocation sites are not yet identified, residents would not give up the houses they already have. And without available sites, they wouldn’t even have other choices.

A multi-agency briefing on the landslide will be organized soon, a DENR official told Rappler.

Mining probe

A red flag for concerned environmentalists was the occurrence of the landslide in close proximity to a gold mine. Environmental groups have called for “a swift and independent investigation to determine the full extent of accountability” of APEX Mining Company Incorporated (AMCI), led by business tycoon Enrique Razon Jr.

That mining operations were allowed in an area declared a no-build zone is cause for alarm, environmental network Kalikasan PNE said in a statement last February 15.

While AMCI has “distanced itself” from claims that its operations played a part in the disaster, environmentalists said the company must still be held liable for not giving adequate measures to protect workers and communities.

A company disclosure from AMCI released February 12 said nine employees were recovered dead from the landslide site. One was injured. Nine more employees are missing and unaccounted for.

“The Maco incident is another stark reminder of how companies have joined forces with complicit government agencies to the detriment of local communities,” Kalikasan PNE said.

“This has all taken place under the framework of the Mining Act of 1995, which has historically provided little space for communities and civil society to assert their right to a clean, healthy, and safe environment against the profiteering of multinational companies and local oligarchs.”

However, another environmental organization pointed out that the extractive industry is on the receiving end of “unwarranted criticism.”

“Such misrepresentation impedes necessary interventions and hampers effective resource allocation on the ground,” said Felix Vitangcol, secretary-general of the Philippine Business for Environmental Stewardship.

Search and rescue teams from the provincial, local, and AMCI continue operations in the incident site.

Because of the incident, mining operations have been limited, with milling activities reduced within the range of 50% to 80%. AMCI said they are expecting lower volume of gold and silver produced and sold by next shipment.

When things go back to normal, the company said, “strategies will be implemented to address production gaps once the rescue, retrieval and clearing operations have been completed.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.