SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

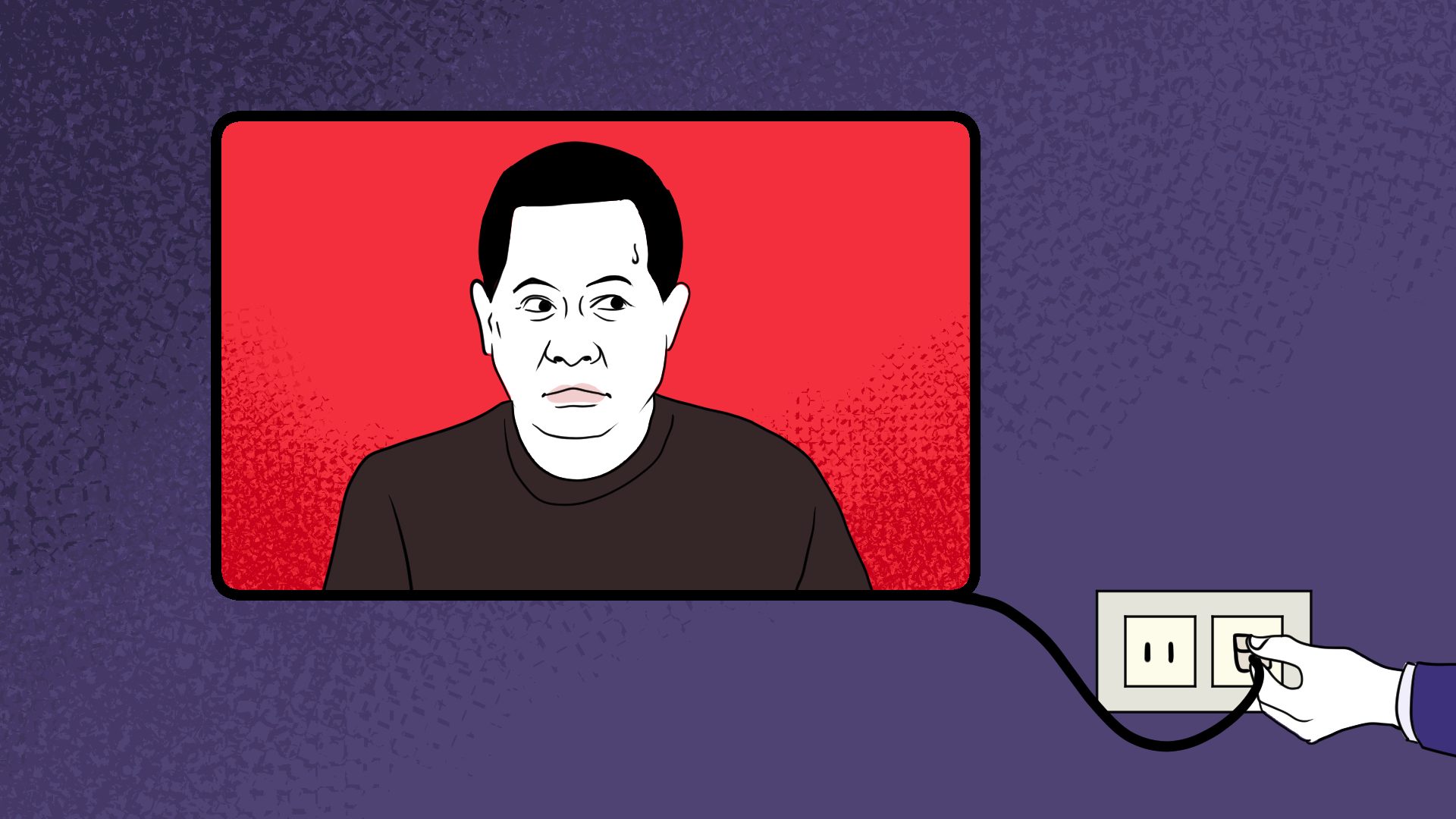

MANILA, Philippines – For the past few years, the self-proclaimed “appointed Son of God” has been dealing with the consequences of the abuse and trauma his victims have alleged.

Pastor Apollo Quiboloy, founder of megachurch The Kingdom of Jesus Christ (KOJC), has been accused of various offenses including land grabbing, sex trafficking, fraud and misuse of visas, and money laundering. Ex-members of the church have had to seek help to fully recover from years of emotional and psychological abuse.

The Davao pastor is also known for his close ties to powerful politicians, particularly former president Rodrigo Duterte. KOJC’s media arm, Sonshine Media Network International or SMNI, has a history of spreading propaganda and disinformation as well as attacking and red-tagging members of the opposition, journalists, and government critics.

But the preacher’s actions have been catching up with him. In 2022, Quiboloy was placed on the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most wanted list, and months later he was sanctioned in the US for “serious human rights abuse.” Quiboloy has said it was a “badge of honor” to be at the center of such a controversy. But since then, he has faced repercussions not just offline, but online as well.

Should a user facing heavy, serious allegations and state-imposed sanctions be allowed to maintain an online presence that empowers their ability to influence? That’s the core question in the Quiboloy case, and his presence on social media prior to his removal by the major platforms.

With Quiboloy being a precedent-setting case in the Philippines, Rappler took a closer look at social media policies and relevant legal resources to understand the grounds of removing human rights violators, and those facing serious allegations and cases on rights abuses, from online platforms.

These also helped us assess whether or not tech companies were doing enough work to foster safe spaces on their respective websites.

Quiboloy deplatformed by Meta, YouTube, TikTok

As of writing, Meta, YouTube, and TikTok have terminated Quiboloy’s official accounts on their platforms.

On Facebook, Quiboloy enjoyed a blue checkmark and 1.2 million followers – his largest audience on any social media platform. Rappler learned in August that Quiboloy’s Facebook page was deleted, and that Quiboloy’s Instagram account was also inaccessible.

In an email sent to Rappler on Thursday, August 31, Facebook parent firm Meta confirmed that Quiboloy’s page was deleted due to its policies on Dangerous Organizations and Individuals.

In this policy, Meta categorizes entities into three different tiers. Tier 1 includes entities engaged in “serious offline harms,” such as terrorism, organized hate, and other large-scale criminal activity. In this tier, Meta includes hate organizations, criminal organizations, and terrorist entities and individuals designated by the United States government. Due to his US sanctions, Quiboloy falls under this category.

Tier 2 includes what Meta calls “Violent Non-State Actors,” or entities that engage in violence against state or military actors, and not necessarily civilians. Tier 3 includes entities that violate Meta’s hate speech policies on or off the platform, or entities that have “demonstrate[d] a strong intent to engage in offline violence in the near future.”

Previously, Meta has enforced this policy for Filipino individuals when it took down the verified account of Chao Tiao Yumol, the gunman involved in the July 2022 Ateneo shooting incident. Meta also removed Facebook posts that would sympathize with Yumol, as their policies explicitly prohibit content that “praises, substantively supports, or represents” dangerous events.

It’s currently unclear what caused Quiboloy’s Instagram account to be unavailable or whether Meta applies the same Facebook rules to Instagram, but Instagram’s Community Guidelines also prohibit “support or praise” for “terrorism, organized crime, or hate groups.”

YouTube’s parent company Google said it terminated Quiboloy’s channel in “compliance with applicable US sanctions.”

The company also has a violent extremist or criminal organizations policy that prohibits content produced by dangerous entities. YouTube says it relies on “many factors” such as government and international designations when determining if an account is linked to a violent or criminal entity. Potentially problematic content that is flagged by YouTube’s automated systems are also reviewed by human moderators, who confirm whether the content indeed violates the company’s policies.

This is not the first time YouTube shut down channels due to legal reasons. In 2018, the video-based platform suspended at least three channels linked to the Syrian government. After the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011, then-US president Barack Obama barred American individuals and companies from providing services to the Syrian government.

Sometimes, new YouTube channels are created to replace previously banned ones. In such cases, Google also told Rappler that while they do monitor for these replacements, the company advised concerned users to make a report to Google, and flag the new channel so they may be able to remove it quicker.

Representatives for TikTok also confirmed Quiboloy’s US sanctions were the basis for banning his account on the platform. In September, TikTok later told Rappler in September that Quiboloy’s account was banned in accordance with its Community Guidelines, specifically its policies on Youth Safety and Well-Being.

Its Youth Safety and Well-Being policies prohibit “sexual exploitation” and “trafficking of young people.” The tech company also told Rappler that off-platform activity “may be considered to help make decisions about a ban.”

What about X?

Despite X having policies on violent and hateful entities and perpetrators of violent attacks, Quiboloy is still active on the platform, where he has approximately 11,700 followers.

X classifies violent entities as those “that deliberately target humans or essential infrastructure with physical violence and/or violent rhetoric,” while hateful entities are those “that have systematically and intentionally promoted, supported and/or advocated for hateful conduct.” The policy also prohibits posts that promote activities of violent or hateful entities.

Any account found to be violating X’s violent and hateful entities will be “immediately and permanently suspended,” according to the tech company.

Likewise, its policy on perpetrators of violent attacks says the company will “remove any accounts maintained by individual perpetrators” or “accounts glorifying the perpetrator(s),” but mostly focuses on “terrorist, violent extremist, and mass violent attacks.”

X also has protocols in place when responding to legal requests that involve accounts on the platform, although such requests may only be submitted by law enforcement or government officials.

Non-legal agents are directed to X’s Help Center to submit requests and report issues. However, X’s Help Center’s topic options are very limited. The closest topic option, which focuses on safety and sensitive content, only covers issues related to harassment on the platform or intentions of self-harm or suicide. An option related to child sexual exploitation is the most applicable to Quiboloy’s case, but it does not cover offline incidents and instead requires users to indicate where they see the incident happening on social media.

Rappler sent multiple emails to X’s press team on separate occasions, but we all received the same automated response: “We’ll get back to you soon.”

X has not had the best track record for platform safety since Musk took over in 2022. For example, it wasn’t until July 2023 that the firm announced plans to reorganize its trust and safety team, responsible for policing harmful content on the platform.

How are laws holding tech companies accountable?

Quiboloy is currently facing US Executive Order (EO) 13818 sanctions, having been indicted for charges including sex trafficking. He is also on the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most wanted list.

Under the EO, as the NGO Human Rights First explained in an FAQ, the US government can sanction any person, including US persons, that “have materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for” persons in the sanctions list or the violative activities of the sanctioned persons.

The EO’s clause on prohibiting “technological support” means tech platforms may be held accountable by the US government if they continue to provide their services to sanctioned individuals.

This is where tech platforms’ terms of service or terms of use come in. These terms include a list of rules or agreements that users must abide by in order to receive the platform’s services.

Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, and X all state in their terms that they remove accounts if required to do so by law.

While Quiboloy’s trial for charges including sex trafficking will not start until March 2024, Facebook and Instagram do have rules that prohibit “convicted sex offender[s]” from using their platforms, should the eventuality of a Quiboloy conviction on the relevant case occur.

Tech platforms have also complied with Magnitsky sanctions in the past. In 2017, the Facebook and Instagram accounts of Ramzan Kadyrov, leader of the Chechen Republic in Russia, were taken down. Kadryov was sanctioned under the Magnitsky Act over “extrajudicial killing, torture, or other gross violations of internationally recognized human rights,” and Facebook confirmed to The New York Times that the tech company had a “legal obligation” to remove Kadryov’s accounts.

Despite this, like in Quiboloy’s case, media outfits noted that Kadryov’s Twitter account was still up and running despite his suspensions on other platforms.

How tech companies handle human rights violators and other dangerous entities on their platforms speaks volumes of how much they value accountability and integrity. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.