SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

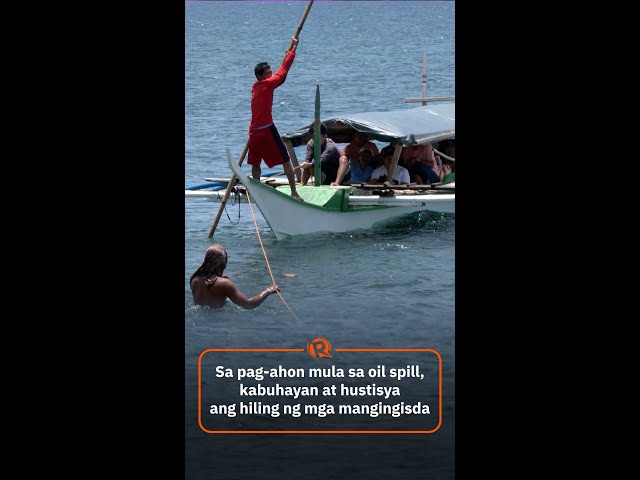

ORIENTAL MINDORO, Philippines – In Pinamalayan, one of the towns heavily hit by the months-long Oriental Mindoro oil spill from MT Princess Empress, some residents are left with no choice but to continue fishing despite the government’s continuing restrictions.

A 26-year-old fisherwoman from Sitio Pating, Pinamalayan, said that with the fishing ban in place for the last four months, they find themselves caught between a rock and a hard place.

Choices narrow further when the stomach grumbles.

“Sa hirap ng buhay at wala talaga pong pumapayag at walang dumadating na sapat na ayuda, napipilitan po talaga kaming maghanapbuhay nang patago,” she told Rappler. (Because of poverty, the fishing ban, and insufficient aid, we’re forced to do our livelihood in secret.)

When Rappler recently visited the fishing community, another Pinamalayan resident recalled an encounter with Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) personnel who reprimanded him for fishing but never charged or took him away. He said the coast guard may have been lenient because they also understand what the fisherfolk are going through.

Fisherfolks’ months of suffering is “worse than the COVID-19 lockdown,” said environmental group Kalikasan, “due to a blanket fishing ban and little to no ayuda (aid), leading to physical and psychological distress across communities.”

As of June 28, the oil spill has affected at least 3,052 fisherfolk in Pinamalayan, with the damage to agriculture in the town alone already reaching P675.48 million.

Pinamalayan is one of the last three towns where the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources’ (BFAR) fishing ban remains in place. Fisherfolk in 10 towns, including Bongabong, Bulalacao, Puerto Galera, have already been allowed to fish since more than a month ago.

What’s taking the BFAR – an agency under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s Department of Agriculture – so long to lift the fishing ban in the last three towns that desperately need their livelihood back?

The agency’s lack of technological capability to conduct faster testing of fish samples in affected municipal waters has drawn out the fishing ban, impeding the long road to recovery.

Slow process

For the fishing ban in Pinamalayan, Pola, and Naujan to be lifted, the BFAR must first ensure that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), or the toxic components of oil, would not be found in fish samples.

It usually takes the BFAR almost a month to test the toxicity of water and fish samples following an oil spill. Collecting samples could take days or weeks, depending on the number and distance of sampling sites the agency is extracting from.

Because the BFAR and the PCG do not have a functional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS) instrument used for analysis, they have to send the samples to other laboratories, such as the Natural Research Sciences Institute of the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. The samples are then analyzed within 10 days to more than two weeks, after which the BFAR releases the results and their recommendations to the public.

In towns where the fishing ban has been lifted, the BFAR found that PAHs had stabilized to much lower concentrations, and water samples revealed municipal waters to be within acceptable standards for fishing activities.

It took more than two months before the fishing bans were first removed in the Oriental Mindoro towns of Bongabong, Roxas, Mansalay, Bulalacao, Baco, San Teodoro, and Puerto Galera. This was followed by the towns of Calapan, Bansud, and Gloria, whose fishing bans were lifted only last May 26.

For the three remaining towns, the results the past four months have so far been inconclusive as the BFAR is still conducting analyses to establish the trend of contamination over a period of time.

Since the BFAR does not have the right equipment to do the collection and analysis faster, the fishing ban in Pinamalayan, Pola, and Naujan continues to prolong the suffering of over 8,000 fisherfolk.

What’s worse is it’s been “more or less two months” since the BFAR last visited Pola to conduct testing, according to Jennifer Cruz, the mayor of the hardest-hit town of Pola.

Environmental scientist Hernando Bacosa, who is involved in the oil fingerprinting or identification of oil in Oriental Mindoro, also lamented the slow-moving process in the collection and analysis of samples.

“One thing I’ve learned about this oil spill is our capacity to respond was really slow,” Bacosa said.

“Investment in research, investment in technology are investments of response,” he added. “And I think we need to have a more cohesive approach in the national government on how we respond to oil spills.”

Bacosa recommended that the BFAR get a functional GCMS instrument for faster analysis of samples and in preparation for future oil spills.

“The analysis could be done in [a] few days if there is dedicated equipment,” said Bacosa.

The BFAR said it had committed to provide P117.86 million worth of emergency and relief assistance for affected fisherfolk in Mimaropa. This covers fuel assistance, post-harvest training, and food aid.

Help is also slow to come

As the testing drags on and the prolonged fishing ban continues to hurt communities, fisherfolk and residents are forced to rely on the government’s cash aid, food packs, and the cash-for-work program. Locals, however, say the help they have received in the last four months is not enough to sustain them.

Following the oil spill, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) gave cash aid of P6,000 ($108.45) to fisherfolk with motorized boats and P3,000 ($54.22) to those with non-motorized boats as part of their emergency cash transfer program.

The DSWD also implemented a cash-for-work program to bring some relief to residents. Locals who joined the cleanup operations under this program got P5,300 ($95.86) for 15 days of work, or around P350 ($6.33) a day – much smaller than what they could get from a day’s worth of fishing. Catching a piece of lobster alone ensures P700 ($12.66) for a fisher, while five kilos of crabs and a kilo of lapu-lapu would get him P350 ($6.33) and P500 ($9.04), respectively.

But there have been delayed payouts from the cash-for-work program, something that residents of Pola and Pinamalayan are already used to by now. While they were already paid for their work for the months of March and April, they are still waiting for their payout for May.

And even before they receive the payouts, they already allot the payouts to pay for their debts.

“’Yung darating po sa kanila na cash-for-work [payout], pambayad lang po talaga sa utang,” said Leamore Paez, secretary of the association of fishers in Barangay Marfrancisco in Pinamalayan. (The cash-for-work income they’re waiting for, that’s only for paying their debt.)

According to Paez, they had to endure a lot – sometimes even to the point of skipping meals – since the oil spill hit their town.

It’s a different story in Pola, where residents had received more food packs and aid compared to other municipalities – partly because their mayor has been assertive in demanding more from the national government.

Cruz said she believes that especially in times of disaster, leaders should be strong-willed when asking for aid for their constituents.

In contrast, help has been harder to come by in Pinamalayan. As of June, residents there have only received eight waves of food packs – just half of what had been promised. Initially, they were told they would get a food pack every week.

Poor leadership, legislation

The Oriental Mindoro oil spill happened less than a year into Marcos’ presidency. Kalikasan dubbed it “one of the worst oil spills in Philippine history” – a disaster that “revealed the abject failure and criminal neglect on the part of the Marcos administration to respond to the economic crisis generated by ecological disasters such as this.”

From a PCG that has yet to modernize to a BFAR that still lacks the proper equipment to produce results within days, Marcos inherited a system that hasn’t learned its lessons from the country’s worst oil spill in Guimaras Island that occurred under the administration of then-president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Even legislation to bring pollutants to justice is sorely lacking.

San Miguel Corporation (SMC) president and CEO Ramon Ang neither confirmed nor denied that their subsidiary SL Harbor Bulk Terminal Corporation chartered MT Princess Empress. All eyes are mainly on the shipowner, RDC Reield Marine Services, which lost their operator’s license and currently faces a criminal complaint connected to the oil spill.

Environmental lawyer and former Department of Environment and Natural Resources undersecretary Ipat Luna said that what came out of the 2006 Guimaras oil spill was a system that held shipowners accountable while letting charterers evade responsibility.

Luna has 33 years of experience as an environmental law champion and had worked on a case with fisherfolk during the Bataan oil spill in 1990.

“Mahirap ang San Miguel kasi sila ‘yung may-ari ng langis pero sa batas, hindi talaga sila ‘yung pinuntirya ng batas,” Luna told Rappler. “Ang nakapuntirya ay ang shipowner at saka ‘yung insurer.”

(It’s hard to go after San Miguel because they may be the owner of the oil but the law goes after the shipowner and the insurer.)

The problem here, said Luna, is that shipowners do not usually have deep pockets, and they always have the option to declare bankruptcy.

If and when this happens, the Philippine government would most likely shoulder the burden of the total cost of rehabilitation.

The DENR had already estimated P7 billion worth of environmental damage. “Had we invested more [on technology], [the damage] could be far less,” said Bacosa.

Way forward

In the aftermath of the Marcos administration’s worst environmental crisis yet, a corporate environment liability law should be passed by the government, said environmental lawyer and former environment undersecretary Antonio La Viña. Under this law, private companies would be made to pay for environmental damage, loss of livelihood, and tourism revenues.

For now, the Philippines has the option to sign the Supplementary Fund Protocol of the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds (IOPC), a convention that seeks to beef up available funds for major oil spill incidents worldwide. The Philippines would have access to $1 billion, or P55.3 billion, if it were a part of this convention, but since it has only ratified the 1992 Civil Liability Convention and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund 1992, it can only get $284 million, or P15.7 billion, from the IOPC.

For marine biogeochemist Irene Rodriguez of the UP Marine Science Institute, the best preparation is prevention.

In an interview with Rappler two months after the oil spill, Rodriguez said it would be better if oil tankers have safer routes away from biodiversity hotspots, if ship crew undergo continual training, and vessels have proper equipment.

This way, future oil spill incidents would no longer threaten biodiversity centers like the Verde Island Passage.

From pushing for stricter legislation, leading agencies in charge of giving livelihood and aid, and investing in better maritime personnel and equipment, the Marcos administration has their work cut out for them to prevent and prepare for future oil spills. – Rappler.com

$1 = P55.30

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.