SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

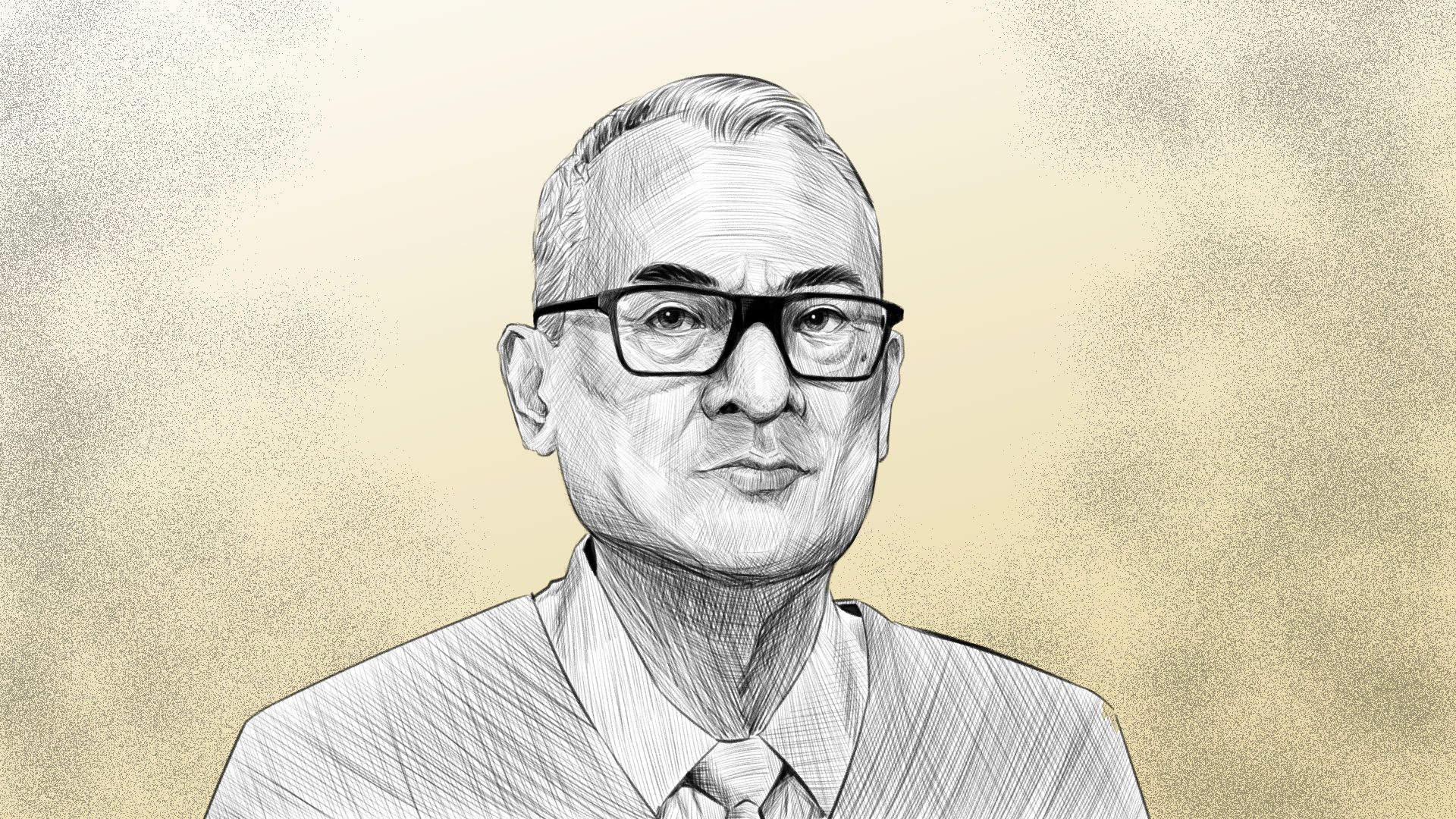

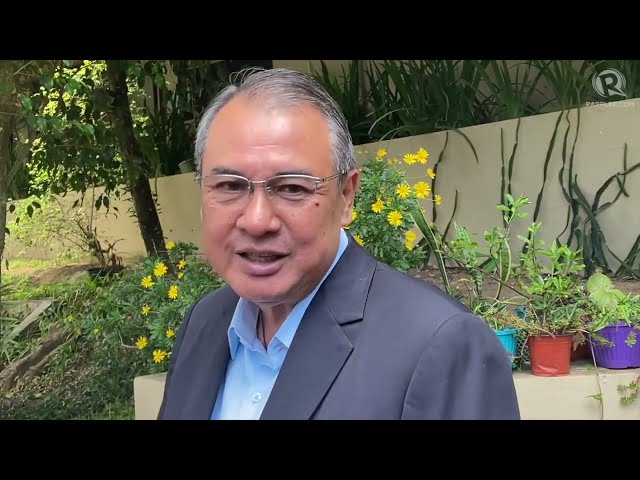

MANILA, Philippines – Alex Gesmundo is a workaholic. He says so himself.

The best part of leading the judiciary, according to the Philippines’ 27th chief justice, is “the challenge of working non-stop,” he told the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) during his application for the top post in March 2021.

“He is a workaholic,” lawyer Isobel Solis, Gesmundo’s former executive clerk of court in the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan, confirmed to Rappler.

In the Supreme Court, before he was appointed chief justice, Gesmundo had taken on lead roles in several committees on reforms. But he was too low profile that his satisfaction rating, according to Pulse Asia in December 2021, was just 31% – a low one for chief justices. In fact, this was the score that ousted chief justice Maria Lourdes Sereno dropped to in December 2017 in the heat of her impeachment proceedings.

But it’s also because out of all the branches, people are least aware of what the Supreme Court does, or who the chief justice is – especially when the chief justice is as quiet as Alex Gesmundo.

“The Chief Justice is a private person,” Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen told Rappler.

He is also averse to the spotlight. When it was his time to hold the traditional Chief Justice Meets the Press, he brought the entire en banc with him, a first for the Supreme Court. It was something that surprised journalists, who did not expect to face all the Gods of Padre Faura when they entered the Zoom link that morning.

But since Gesmundo took the helm in April 2021, the Supreme Court has done a few rare things that merited headlines: it issued a strong and rare public statement against attacks on lawyers and it scrapped the contested power of Metro Manila judges to issue search warrants outside of their jurisdictions. Remote search warrants had been the judicial basis of raids conducted by state agents that ended up in killings, like the Bloody Sunday incident in Calabarzon.

Addressing that problem further, the Court required police officers to wear body cameras at a time when killings by state forces have been alleged at the International Criminal Court to have amounted to crimes against humanity. All that under a human rights committee that gained new life after Gesmundo came on board.

The incremental transition to digital processes – such as allowing e-payments which might seem late to the general public, but actually revolutionary for an old-fashioned Philippine judiciary – enhanced Gesmundo’s name recall somewhat among the Court’s users: the lawyers, litigants, and even employees.

The stabilizing force

“I just want to emphasize that whatever rating I achieve, they just put my name, but it is a collective effort of the entire Supreme Court, not only of the justices but equally important, people in the judiciary, because the most important people there is who the survey takers talked to, perhaps they have good experience in dealing with the lower courts. We take care of the lower courts because that’s the people’s first encounter,” Gesmundo told reporters in a reluctant interview on the sidelines of an off-the-record media training in Baguo in April 2022. He was responding to the 27% rating he got in that month’s Publicus Asia survey.

Gesmundo declined Rappler’s request for an interview for this story and said any interview must be done with the entire en banc.

“He has introduced a new level of collegiality among his colleagues, always consulting on the most critical decisions that would impact on the judiciary,” said Leonen, who recommended the scrapping of remote warrant powers of Metro Manila judges and the requirement of body cameras.

Collegiality is an honored, and very crucial virtue, in Padre Faura. So is seniority. When Gesmundo, then only the fourth most senior on the bench, was chosen chief justice by former president Rodrigo Duterte over the most senior who applied – now retired senior associate justice Estela Perlas Bernabe – there were concerns about the acceptability of his appointment to the bench.

After all, bypassing seniority was what caused Sereno trouble before. It resulted in a quo warranto ouster that shook the institution to its core. It didn’t help that Duterte appointed a revolving door of chief justices – three, Teresita Leonardo De Castro, Lucas Bersamin, and Diosdado Peralta, in only three years. Four, if the acting capacities of Antonio Carpio are counted.

It seems Gesmundo knows, and is very conscious of, the need to be collegial to stabilize a highly-politicized Court. The result was obtaining the approval of the people crucial to his success as chief justice: his colleagues on the bench.

“He is a decent man and a leader who really looks out for his troops,” said a fellow justice.

He also enjoys approval among trial court judges.

Said one: “As an administrator, I believe he is doing good in the judiciary. Based on the circulars he issues, I think he is responsive to existing conditions, and efficient and sensitive to the needs of the people in the judiciary.”

“He leads by example. He is thus a unifying force in the judiciary,” said Solis, who worked for Gesmundo in the Sandiganbayan for a decade

His rulings, especially on anti-terror law

Those who cover or observe the Supreme Court know all too well the myth of the deliberations room: the supposed shouting matches, the heated debates which remain myths because nobody else outside of the 15 magistrates are allowed in the room, except those who serve their food.

In that room, said Leonen, Gesmundo “encourages debate among his peers, never showing any insecurity with his own position, magnanimous when he wins a vote but respectful when he loses one.”

When it comes to the end result, or his rulings and opinions, Gesmundo would not be the most favorite justice of libertarians. His opinions on the anti-terror law could even make him the least favorite for some.

During his tenure in the Supreme Court, Gesmundo has never voted against Duterte’s interest. His name was floated as a potential swing vote to overturn the 8-6 Sereno ouster in 2018, but he still voted to oust on appeal, as he did the first time.

For the anti-terror law, Gesmundo’s opinion was largely pro-government and in fact won the close votes on some crucial issues. Although he is not the ponente, his opinion became the majority ruling that retained the clause that makes recruitment to a terror group a crime. Six justices, including the ponente, retired justice Rosmari Carandang, wanted to remove it for being ambiguous and prone to abuse, but Gesmundo won the vote, 9-6.

Gesmundo also won a most crucial vote, and by a hairline 8-7 vote at that, to retain the hotly-contested power of the anti-terror council (ATC) to designate a person or a group as a terrorist, based only on the council’s own determination. The ATC could do this without having to go to court, or even notify the designess, much less give them a chance to defend themselves.

What petitioners consider a win – big or small, depending on which petitioner group you ask – is the Court striking out a clause in Section 4, or the definition of terrorism in the law. This is the so-called “killer caveat” that would have given law enforcement a lot of latitude in interpreting dissent as terrorism. Gesmundo voted, although he lost, that it was not unconstitutional.

Gesmundo voted to take recognition of only four of the total 37 cases, saying that the rest did not pass the test. A big issue in the anti-terror law was the standing of the petitioners when they filed the case itself, considering that they had not been prosecuted or charged.

When the petitioners filed their appeal, some feared it could make a turn for the worse and just go the Gesmundo route. The junking of the appeals in the same way – meaning retaining the Section 4 win on the definition of terrorism – gave relief to some extent.

“I was not surprised with his ruling on the anti-terror law because that is his background, to defend what the State does,” said law professor Tony La Viña, a counsel for the petitioner group of indigenous peoples.

“In the same way that Justice Leonen, being a human rights lawyer all those years before becoming a justice, you would expect him to be more sympathetic to petitioners. Based on his decisions, Chief Justice Gesmundo is inclined to give the benefit of the doubt to the State,” La Viña told Rappler.

Immediately after passing the Bar in 1985, Gesmundo worked as a trial attorney at the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) and rose through the ranks to become an Assistant Solicitor General by 2002. Between 1998 to 2001, he was on seconded appointment as commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG). He was appointed to the Sandiganbayan by former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2005, and to the Supreme Court by Duterte in 2017.

It’s been observed that in the judiciary, judges who were career government officials have a tendency to vote in favor of government.

Conservative justice

“His opinions indicate that he generally may not be a big fan of the expanded and pro-active exercise of judicial review. Such apparent judicial conservatism seems to run through most, if not all, his votes at the Bench, even as we have to note that they are all well-written, eloquent and powerful,” said Edre Olalia, president of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers.

His concurrences to Duterte wins, and his ponencia on junking the challenge to Duterte’s pandemic Bayanihan Law, have shown his inclination to defer to the political branches. In his JBC interview, Gesmundo said he was against judicial legislation, and if there was a need to change something about a law, “Congress can legislate on those matters.”

“Because judicial legislation may technically provide something that’s not in the law, so if the reason or the rationale of the decision is to call the attention of Congress to pass a specific law as reflected in the decision, Congress must address that,” said Gesmundo.

This is a more conservative judicial principle compared to, for example, Bernabe who, although she considers herself to be a textualist, or one who sticks to what the law says, declared in her own JBC interview that “if the intent is vague, I would apply reason, logic, and societal implications of that ruling, and fairness of that ruling.”

“For some justices, sometimes we think there was no integrity to the decision, just siding with the State for its own sake. With Chief Justice Alex, we see the consistency in his reasoning and the consistency of his siding with us on search warrants and protecting lawyers,” said La Viña.

Consistency and predictability, even when you don’t agree with the decision, are also valued traits in the Court. Generally, you wouldn’t want a Court that flip-flops and a Court that reverses precedents all too often. There would be instability of laws when that happens.

Leonen said Gesmundo knows it’s important that “the Court always acts collectively and, during critical moments, unanimously.” La Viña said Gesmundo being open to being convinced to vote with the other justices, or convincing the Court to vote unanimously, is what makes him somewhat “the perfect chief justice for the times.”

But “consistency in decisions need not require symmetric identity all the time,” said Olalia.

“We prefer bias on the side of the people, which, after all, is the decisive component of a State. The issues are enormously larger than any one’s career and record. Our courts must be responsive to pleadings of the people for judicial redress and refuge against human rights abuses,” said Olalia.

Gesmundo before being CJ

Gesmundo was born November 6, 1956 to parents Juan and Zenaida, a farmer and public school teacher, respectively. He obtained a degree in economics from the Lyceum University of the Philippines, before going to Ateneo Law School where he joined the fraternity Utopia. Among the Utopia alumni who joined the Supreme Court are the late former chief justice Renato Corona, retired associate justices Andres Reyes Jr., and incumbent associate justice Rodil Zalameda.

Gesmundo graduated from the Ateneo Law School in 1984, a year ahead of another important Atenean, First Lady Louise Araneta Marcos. Gesmundo has been inhibiting from the graft conviction appeal of former first lady Imelda Marcos due to his stints at the OSG and PCGG, the two agencies that prosecuted the dictator’s wife.

Before he started his career in government, he was a research analyst of the newspaper Business Day and a market research officer of the Australian embassy in Manila.

Gesmundo’s family, including his three children, are based in the United States. Solis said despite this, Gesmundo “rarely took personal leaves of absence. The longest he has taken a vacation to be with them in any given year is only two weeks.”

Long tenure

The Supreme Court has a long way to go in making the public truly understand its work and its role in a democratic society. People’s awareness of the Court and the chief justice has not improved significantly.

Gesmundo said in Baguio that his priority is making information about the court processes easier to access – not so much decisions of the Court, but simple things like what to do or who to call when one is arrested.

“It’s part of our strategic plan, the strategy is 2022 to 2026 but it comes in stages. It’s like doing a puzzle, you do it piece by piece until one day you see the entire picture,” Gesmundo said, adding that they were looking to expand their social media channels to even include podcasts.

Nowadays, the Supreme Court instagrams court activities and uses quote cards for some of its decisions.

When Gesmundo was chosen chief justice in 2021, it came as a surprise to the general public because he was virtually unknown. He had no known links to Duterte. He told the JBC the reason he applied for chief justice was just because he wanted to “honor the endorsement” of the council. The five most senior justices – Gesmundo was fourth at the time – are always automatically nominated. Leonen and fellow Aquino appointee Associate Justice Benjamin Caguioa declined.

Legal circles had been abuzz for some time with Gesmundo being chief justice because he would be at the helm until 2026. Long tenures are always attractive to powers-that-be. But they also paint good prospects for reforming the judiciary.

“Would [a long term] prove significant and [be] good for the judiciary? I will stick out my neck out and say yes,” wrote Supreme Court spokesperson Brian Keith Hosaka in the court’s magazine Benchmark. “Chief Justice Gesmundo will have more than four years to institute reforms in the judiciary, but then again this might just be too short.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.