SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

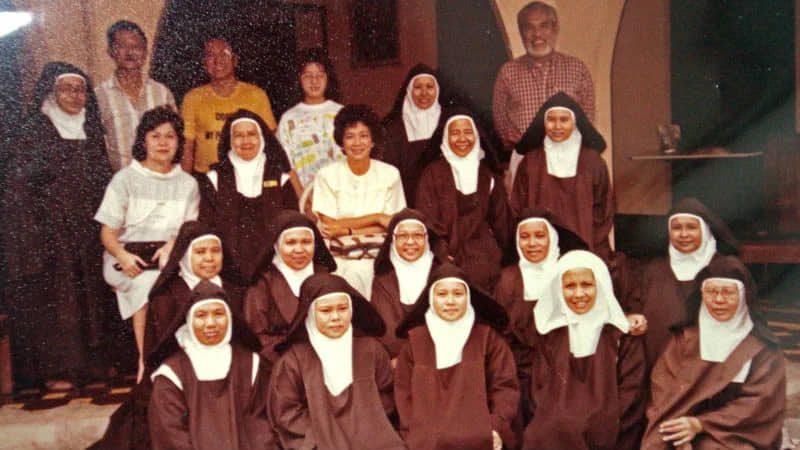

CEBU CITY, Philippines – The nuns who hid former president Corazon Aquino (then a presidential candidate) in 1986 did so to show “unity” against the dictatorship, a University of the Philippines assistant professor told Rappler in an interview.

“[I]t’s a really significant historical moment because you have here the religious community intervening in a political, very critical political situation so yeah that was really important and it showed that the unity of different sectors, from the church hierarchy, you have the traditional politicians who were fed up of the dictatorship,” Karlo Mongaya said during Rappler’s Voices from the Region program on Saturday, August 20.

What Cory Aquino did with the Carmelite nuns on the evening of the 1986 People Power Revolution became an issue when the trailer for Maid in Malacañang falsely depicted the nuns as playing mahjong with Aquino.

The film is based on the questionable account of Senator Imee Marcos and not the dozens of actual historical records available.

“The truth was that we were then praying, fasting, and making other forms of sacrifices for peace in this country and for the people’s choice to prevail,” Sister Mary Melanie Costillas, prioress of the Carmelite Monastery, said in a statement published on Tuesday, August 2.

Rappler interviewed the nuns who were with Aquino that night in February 2016 and said they allowed Cory into the cloister because they recognized her as the “rightful” president of the Philippines. (READ: ‘Are we safe here?’ The night Cory Aquino hid in Cebu)

Carmelite Mother Superior Aimee used her prerogative then to allow a non-Carmelite priest, nun or layperson to enter the papal enclosure without permission from the Pope. This discretion is usually only reserved for heads of state.

Mongaya said he thought that the depiction of the nuns playing mahjong was “disrespectful” when the trailer of the film went online.

“Well I thought it was really disrespectful and even our leaders, politicians, who are in fact allied with the current administration, I think they share the same sentiment,” Mongaya said.

“It’s not just because this is your candidate that you support, that you are given the right to take liberties with the truth and with historical facts. So it’s really disrespectful. It’s one thing to campaign for a candidate, you’d like to tell things about that candidate, or about their side of the story. It’s another thing to distort history and to disrespect people there,” he added.

Cebu resistance triggered by Ninoy assassination

The anti-Marcos sentiment in 1986 did not happen overnight, however.

The August 21, 1983, assassination of opposition leader Ninoy Aquino had triggered massive rallies and resistance against the dictatorship, Mongaya said.

“But from then on, we could see a subterranean change after the killing of Aquino, in Cebu,” Mongaya said.

He said that while there was already a growing protest movement, his death created a broad unity between mass organizations, the youth, and traditional politicians.

“Mas nangisog ang kining mga traditional politicians and kining mga sectors, they were now linking their issues to the national and political stage (The traditional politicians have become angrier and stronger and different sectors are now linking their issues to the national and political stage),” the academic added.

But while Aquino’s assassination triggered resistance and protests in the province, Cebu was not immune to disillusionment of the government that came after the Marcos regime and its failure to make significant electoral reforms.

Over 36 years since Cebu became known as an opposition bailiwick, the province overwhelmingly chose the dictator’s son Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as president in the 2022 election.

“You have the machinery, you have the infrastructure of network disinformation, you have all of the traditional politicians lining up with the administration picket and that was really the formula for a big success even in Cebu which was formerly an opposition bailiwick,” Mongaya said.

The Marcos-Duterte campaign was supported by popular incumbent Governor Gwen Garcia and her One Cebu party, the dominant party of the country’s most vote-rich province.

But despite the challenges opposition to the administration of current President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. might face, Mongaya said they can learn from the experiences of the activists who fought the dictatorship of his father.

“One of their favorite slogans that they really shout in the streets ‘is this: ‘Makigbisog, ayaw kahadlok’ or ‘Do not be afraid, dare to struggle.’ And I think that is one of the key principles that we should hold on to today, because during their time, you really have to have the courage, the audacity to try to change things because that was under a dictatorship,” the history researcher said.

The other lesson he said, is to take note from Marcos Jr.’s campaign slogan itself and “build unities.”

“Another thing would be, this is also the story of the protest movement in Cebu, that’s the need to build unities. The protest movement in Cebu after the Marcos Martial Law was declared began with the urban poor, the basic Christian communities organized by the Church, and the student movement,” Mongaya said.

“But eventually, they had to build unities across issues faced by different sectors because they are facing one situation which is an authoritarian situation… So they built a broad united front. Eventually, this front was strong enough to be able to overcome the repression of the Marcos dictatorship and that was the culmination, the People Power [Revolution],” he added. – with reports from Jonette May Manalo/Rappler.com

Jonette May Manalo is a Rappler intern

Watch more episodes of Voices from the Regions here:

- Voices from the Regions: People Power beyond Manila

- Voices from the Regions: Bacolod’s Luke Espiritu and his bid for the Senate

- Voices from the Regions: Robredo’s pink campaign in Northern Mindanao

- Voices from the Regions: Margot Osmeña and her bid for Cebu City mayor

- Voices from the Regions: ‘Kakampinks’ in Marcos country

- Voices from the Regions: Covering the Cebu campaigns

- Voices from the Regions: LGBTQ+ in media

- Voices from the Regions: Safety and tourism in Mindanao

- Voices from the Regions: ‘Tinang 83’ and genuine land reform

- Voices from the Regions: What happens when your local media is under fire

- Voices from the Regions: Who benefits from Cebu’s Carbon Market redevelopment?

- Voices from the Regions: VisPop and why local music matters

- Voices from the Regions: The truth about Cory, nuns, and mahjong

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Wide Shot] Peace be with China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/wideshot-wps-catholic-church.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=311px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] A critique of the CBCP pastoral statement on divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-cbcp-divorce-statement-july-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=285px%2C0px%2C722px%2C720px)

![[The Wide Shot] Was CBCP ‘weak’ in its statement on the divorce bill?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/cbcp-divorce-weak-statement.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=258px%2C0px%2C719px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] The challenge of unsavory company](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-unsavory-company.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=238px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.