SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

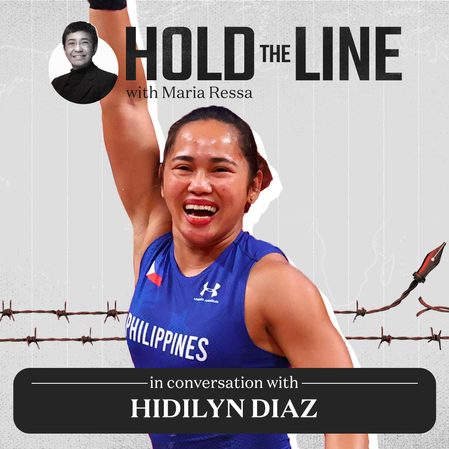

The common thread isn’t lost on Hidilyn Diaz.

In the Philippines’ best Olympic showing ever, the four athletes who delivered the goods all came from Mindanao, the southern island long battling poverty and security threats.

It is in this poorest island where the country’s champions emerged, with Diaz leading the way as the weightlifting star captured the Philippines’ first Olympic gold medal.

“Galing po kasi kami sa hirap talaga,” Diaz told Rappler. “Lahat naman siguro mahirap. Pero mas grabe ‘yung determinasyon ng pagiging Mindanaoan.”

(We really came from poverty. I guess everything is difficult. But the determination of Mindanaoans is different.)

Diaz, who already made history in 2016 when she became the first Filipina to win an Olympic medal in the 2016 Rio Games, grew up in Barangay Mampang, Zamboanga City, where her father worked as a tricycle driver.

A young Diaz also helped sell fish and vegetables as her parents tried to raise a family of six children.

It’s quite a similar storyline lived by the three Filipino boxers who also made history in the Tokyo Olympics.

Nesthy Petecio, Carlo Paalam, and Eumir Marcial helped the Philippines seal a one-gold, two-silver, one-bronze finish, the country’s biggest medal haul in 97 years of competing in the world’s biggest sporting event. The feat also made the Philippines the top performing Southeast Asian nation in the Tokyo Games.

All three also came from Mindanao. And like Diaz, all three took up boxing to fight their way out of poverty.

Petecio bagged the women’s featherweight silver medal to become the first Filipina boxer to win an Olympic medal. She hails from Barangay Tuban in Sta. Cruz, Davao del Sur, where her father worked as a farmer.

Growing up, Petecio and her siblings also picked up chicken droppings to be sold as fertilizer.

Paalam copped the Olympic men’s flyweight silver. The 23-year-old fighter – the youngest in the Philippine boxing delegation – comes from a family of 10 in Talakag, Bukidnon, before they eventually relocated to Barangay Kauswagan, Cagayan de Oro.

As a boy, Paalam scavenged for scraps in a stinking sanitary landfill in Barangay Carmen, earning him the nickname “Pipi Lata” or tin-can crusher from one of his early coaches.

Marcial, a Zamboangueño like Diaz, won an Olympic bronze in the men’s middleweight class. He was only seven when he got into boxing and made it into the national team as a teen.

Then a junior national boxer, Marcial received a basic allowance – which he sent to his parents who are raising five children. This eventually helped his mother put up Eumir Store, a retail store located at the crossing of Barangay Lunzuran and the city highway.

Diaz noted that their Olympic journeys all started from the grassroots, from the local government which paved the way for them to be discovered, and eventually honed by the rigid training in the national sports programs.

“Nagma-matter ito (athletes’ development) sa programa ng LGU (local government units),” said Diaz, who started in local tournaments in Zamboanga.

“Ang alam ko kasi maganda na ang LGU project ng Zamboanga City dahil kasi dalawa na kami [na naging Olympic medalists].”

(The program of an LGU matters to the athletes. I know Zamboanga City has a good LGU project because they’ve now produced two Olympic medalists.)

Marcial also got discovered by slugging it out in local bouts as a young boy, winning his first fight at the “Beer na Beer Tournament” at Plaza Pershing in downtown Zamboanga.

A pre-teen Paalam similarly joined weekly matches in Cagayan de Oro and was discovered in 2009 when he fought at the local “Boxing at the Park.”

Petecio was also just 11 years old when she boxed against boys in local bouts in “Araw ng Davao.”

“We are encouraged by this. We will produce more Carlo Paalams,” said Cagayan de Oro Mayor Oscar Moreno, whose local boxing program turned into a launching pad for several boxers from the province.

Zamboanga also prides itself for being home to two Olympic medalists, with Mayor Maria Isabelle Climaco-Salazar noting that the incredible feat underscored “the resiliency, bravery, and determination of the Zamboangueños to win life.”

The Philippine Sports Commission led by chairman William “Butch” Ramirez has often emphasized the importance of grassroots projects. It’s a system, he said, coupled with investments in identified elite national athletes, that boosted the national sports program to pull off the historic Olympic campaign.

“I think it gives everyone more impetus to plan and start their preparations,” said Ramirez.

“Being in government, we had to take the first steps to ensure a rich ground for a successful elite sports level by strengthening grassroots sports,” the PSC said in a statement.

“The government, from scouting, identifying, developing and nurturing our athletes in the grassroots and grooming them for the national team at the elite level, plays an active role. In this role, the PSC is not alone.”

Some pointed out, however, that it’s no coincidence that all four Olympic winners hail from Mindanao, alluding perhaps to a preferential treatment, with President Rodrigo Duterte a proud Mindanaon, and Ramirez, the sports chief, also hailing from Davao.

Diaz, though, was quick to counter.

“Sa sports kasi kahit taga-Mindanao ka o hindi, walang ganoon,” she said. (In sports, it doesn’t matter whether you are from Mindanao or not.)

The 30-year-old weightlifting star, in fact, pointed out how she even had to ask for financial assistance even after winning a historic Olympic silver in 2016.

“After winning the Olympics sa Rio, noong nagsalita ako, parang iba ‘yung dating sa kanila,” she said. “Naninibago sila na when nagsalita na ako, natuto akong i-voice out kung ano ‘yung pangangailangan namin, medyo parang nanibago sila.”

(After winning in the Olympics in Rio, I started speaking out and it came across differently. They weren’t used to it, that I was speaking out, that I learned to voice out our needs. It was kind of unusual for them.)

That she came across as demanding and difficult hurt Diaz, but she tried to understand that maybe the situation is just all new for most sports officials.

While the sporting row eventually got sorted out, Diaz also got help from private corporations, with tycoon Manny Pangilinan’s MVP Sports Foundation, she said, the first to answer her plea.

“Sinubukan ko intindihin, baka hindi nila alam paano nga ba, paano i-build ang isang atleta para manalo sa Olympics,” said Diaz. “Kasi siyempre, for how many years ako ‘yung first athlete na after winning a silver medal in the Olympics, nagpatuloy pa rin akong maglaro. ‘Yung next goal ko is the gold for the Philippines.”

(I tried to understand, maybe they just don’t know how it’s like, how to build an athlete to win in the Olympics. Of course, after how many years, I was just the first athlete who won an Olympic silver medal who decided to continue competing. My next goal was to win a gold for the Philippines.)

“Para sa akin na-frustrate lang ako kasi siyempre, gusto ‘nyo ako manalo ng gold, akala ko ibibigay na kung ano ‘yung request, pero nahirapan ako ipaintindi. Buti na lang naintindihan nila later on na kailangan ko ng team.”

(I got frustrated of course because you wanted me to win a gold, I thought you’d grant my request, but I had a hard time making them understand. Good thing, they eventually understood that I needed a team.)

The PSC eventually granted Diaz’s request as she emphasized that even for an individual sport like weightlifting, she needs a support crew.

“We have limited resources but we saw her potential so we took the chance,” said Ramirez.

With one less worry, Diaz focused on training with Team HD (Team Hidilyn Diaz), which is composed of Chinese coach Gao Kaiwen, strength and conditioning coach Julius Naranjo, nutritionist Jeaneth Aro, and sports psychologist Karen Trinidad.

“Hopefully, it will serve as a lesson sa sports leaders natin na sana pakinggan kung ano ang pangangailangan ng isang atleta,” said Diaz. “Sana suportahan natin ang bawat Filipino athlete hindi lang sa laro, kung hindi sa preparasyon din.”

(Hopefully, it will serve as a lesson for our sports leaders to listen to the athletes’ needs. Hopefully we can support the Filipino athletes not just when they’re competing, but also when they’re preparing.)

In the end, of course, it still all boils down to the athletes on how far their hard work and drive could propel them.

For the four Mindanaon Olympic medalists, there was clearly no lack of motivation. They all wanted to make the country and their families proud, so a victory always hits home. And of course, there’s that longtime hope that sports could be their ticket out of poverty.

“Itong medal na ito ay simbolo ng buhay ko. Isa akong mangangalakal at itong medalya ay gawa sa mga sirang gadget po,” said an emotional Paalam as he held his Olympic silver medal, which the Tokyo Games made from recycled electronic devices.

(This medal symbolizes my life. I was a scavenger before and this medal was made from broken gadgets.)

“Sa basura siya galing, kaya nai-connect ko po siya sa buhay ko.” (It came from trash so I am able to connect it to my life.)

More than just a victory in the sporting arena, it’s really a triumph in life for Diaz, Petecio, Paalam, and Marcial.

And as the much deserved cash incentives and rewards continue to pour in for the four Filipino sport heroes, their shiny Olympic medals have truly been symbolic of how they’ve turned their lives around from their humble beginnings in Mindanao.

“For me, this bronze is gold,” said Marcial.

It couldn’t be any more true. – with a report from the Mindanao Bureau/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.